“Speed-faithing” Engages “Big Questions” and Builds Bridges of Empathy and Connection

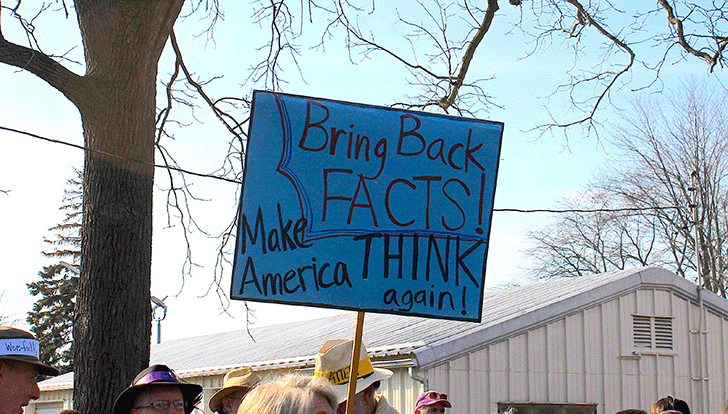

Photo: Women’s March in Seneca Falls, NY, on Jan 21, 2017, by Lindy Glennon.

“What is the origin and meaning of your name?” asks the facilitator to the students who stand facing one another in two large circles in the middle of the room. “You have two minutes,” reminds the facilitator. “Remember, this is more a serial monologue than a dialogue. Each conversation partner should take a one-minute turn speaking while the other partner listens and then you will switch.” She can barely get these words out before students begin speaking animatedly with their partners.

After two minutes, she shouts above the growing din, “now stop, thank your partner, and students in the outside circle, shift one person to the left.”

Over the course of the next twenty to thirty minutes, students continue to speak with multiple conversation partners, sharing their thoughts on questions like, “Where do you feel most at home and why?”; “Did you grow up with a particular religious or spiritual tradition or a particular world view…what was it?”; “Do you adhere to that or to another tradition or world view now?”; “What is one of the core values that you hold that you would attribute to that tradition or world view?”; “What is a stereotype or an assumption that others have about those who share your religious tradition or world view that you would like to dispel?”; “What else would you like me to know about you that you haven’t already mentioned?”

This ice-breaker activity is called “Speed-faithing,” (like speed-dating). Sometimes it is also called, “Talk-Better-Together.” It was, as far as I know, first used by Interfaith Youth Core’s student-trainers at their regional Interfaith Leadership Institutes held each year in Atlanta, Chicago, and Los Angeles. This organization, founded and directed by Dr. Eboo Patel, seeks to make “interfaith cooperation a social norm within a generation,” by training student leaders to build positive relationships on their campuses among people who orient around religion differently.

Today, speed-faithing is an activity used on a growing number of campuses throughout the country to encourage students to engage in the kinds of conversations that can very quickly build bridges of connection and empathy where none have existed before. As an exercise in meaningful sharing, it provides students with opportunities to talk about the “Big Questions” in their lives.

Before beginning the activity, students commit to practice “safe-space-dialogue-guidelines.” They agree to use “I” statements when they speak. In other words, this is not a time for proselytizing or debating Truth claims—but to speak as experts and owners of their own life-histories and experiences. They agree to speak vulnerably and honestly, but only as vulnerably as they are comfortable. Recognizing that a deeply held personal belief might run exactly counter to what their conversation partner believes, they agree to listen with a certain level of personal detachment, and to give one another the benefit of the doubt when truth claims clash. They agree to hold what is shared tenderly and to fiercely protect the trust that their conversation partner has placed in them—what is shared in speed-faithing events, stays in speed-faithing events.

Over the last two years, I have facilitated this activity more than twenty times. I have used it in the classroom, at student-centered gatherings, in “Better Together Interfaith Ally” training workshops, and even in community settings where people want to strengthen their connections with one another. Every time I have, the results have been transformative, powerful, and immediate.

Each time we debrief the activity, participants note with surprise how easily they were able to talk with their conversation partners about topics normally considered “taboo” or “off limits” (especially in public university settings like ours). They note how good it felt to share some of their personal story—even with strangers—in an environment where they knew they wouldn’t be judged or censored. They note, with surprise, how much diversity of thought and opinion they experienced when sharing and listening to their partners—even when they shared the same religious (or nonreligious) backgrounds. They always comment on how much similarity they found between their own core values and those of conversation partners whose worldviews or spiritual commitments are very different than their own. And, they always, always, wish that there was more time to share and to listen. They leave the experience hungry to know more.

Why Speed-faithing is Useful on Public University Campuses in the Intermountain West

The Intermountain West is a unique region in the United States because of its vast and open landscapes, its low population, and the relative lack of opportunity for university students to engage daily with those who are religiously “different” from themselves. We know that, in the wake of the recent presidential election, religious “others” are increasingly targeted on college campuses. Where religious diversity is lacking and where students are ignorant of their religious privilege, the climate is certainly ripe for the kind of hate speech that stems from lack of empathy and connection. Perhaps because of this lack of diversity, there is an especially urgent need to build student capacity for positive interactions among those who orient around religion differently in this part of the country.

We know from the literature that authentic sharing, appreciative listening, and meaningful dialogue are necessary pillars when constructing these bridges of empathy and connection. Students want to have these kinds of dialogue on campus—both in and out of the classroom. This is, at least in part, because college students are in the business of exploring the “big questions” and “worthy dreams” that give meaning to their lives. A big part of this exploration includes the religious and spiritual orientations that are foundational to their identities as “emerging adults.”

On my public university campus in Utah, for example, a recent survey of incoming freshmen revealed that almost 90% of our students have at least some interest in having these discussions. This is the case whether they are members of the “majority” religion (about 70% of our incoming freshmen self-identify as being members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or “Mormons”), members of “minority” religious groups, or spiritual but not religious. Similarly, whether students identify as “post” religious, as secular humanists or agnostics, or even claim a “faith commitment” to atheism, our students want to explore how their experiences and allegiance informs their identities—both in and out of the classroom.

But, on university campuses such as mine, it is also easy for students to presume that lack of visible diversity means lack of difference. On our campus, students frequently choose to add to an illusion of homogeneity by choosing to keep their own religious and spiritual commitments “closeted.” When we asked why, during a recent campus-climate study that I directed, students told us that it’s because they don’t feel safe “outing” themselves to others.

Whether Mormon or Buddhist, atheist or spiritual, our study found that students prefer to keep their faith-commitments private because they feel vulnerable and afraid of judgment. Even though students say they want to build bridges across religious-divides in order to feel more connected to members of the campus community who don’t share their faith-commitments, they’re not quite sure how to break the ice or how to get these conversations started.

Speed-faithing has helped to fill this void on our campus. It is an icebreaker that has—on every occasion I have facilitated it—helped students to make new connections. It has helped them to move beyond their comfort zones while opening space for more meaningful interactions with religiously different others.

Speed-faithing as a First Step Towards More Meaningful Connection

There is a decades-old wisdom that has guided religious studies classroom management. This wisdom has suggested—or at least presumed—that students leave their religious commitments at the classroom door when entering into the nonsectarian study about religion that religious studies exemplifies. The kinds of topics that speed-faithing addresses have often been discouraged, especially on public university campuses like mine.

But authors like Jake and Rhonda Jacobsen have countered this narrative. They have affirmed the importance of supporting the kind of dialogue that encourages students to consider how their faith-commitments impact other aspects of their lives. Opening this space has always seemed important to me and it has guided my teaching since the beginning of my career. As an anthropologist, rather than a religious studies scholar, I have actually had less “push-back” in the classroom when engaging students in these kinds of conversations about how their personal values impact their abilities to perceive the world. Perhaps this is because, as Ruth Benedict once put it, “the purpose of anthropology is to make the world safe for human differences.” And, at least in my mind, religious difference has never been excluded from Benedict’s dictum.

But the need to foster these kinds of dialogue seems even more urgent now, since the election. Because we are experiencing a moment in history where religious identities are increasingly politicized and polarized, we must provide our students with the tools for countering poisonous and divisive rhetoric, now more than ever before. For as Eboo Patel has noted, “If we don’t cultivate and advance a positive public language of religion we simply forfeit the territory to people who have poisonous public language.”

A very poignant example of the ways that religion can polarize Western communities was illustrated in a New York Times article last year about the small town of Pocatello, Idaho, which is home to Idaho State University, just ninety miles north of my home institution. When that university began heavily recruiting international students from oil-rich Muslim majority countries in the Middle East a few years back, Pocatello residents and Idaho State University students reacted. As the title of that March 21, 2016, article reported, “The Middle East Came to Idaho State: It Wasn’t the Best Fit.”

As the New York Times reported, normally friendly Westerners reacted. While some residents lobbied the city to block the construction of a proposed mosque, others lashed out on campus, leafleting cars with Islamophobic messages. One woman who was interviewed for the article reported that she lived in a state of fear “that a jihad was going to occur in Pocatello.”

Some of the affected Muslim students countered. They complained of discrimination on campus—including being accused as “terrorists.” Many decided to transfer to other universities or to leave the United States altogether. This caused a loss of significant revenue to the university.

When this pre-election example is coupled with the rise of hateful rhetoric and poisonous speech that campuses have experienced in the days and months since the election, it is clear that we need to prepare our students for more positive engagement with religious others. As the Pocatello story amply illustrates, increasing religious diversity alone doesn’t necessarily translate to respect or appreciation for difference: Instead, this is something that we must cultivate.

In recent weeks, “religious freedom” legislation and policies that mandate “free-speech” zones on campuses are popping up all over the country. While perhaps well intended, these certainly don’t guarantee that all religious (or nonreligious) points of view get equal voice. Instead, finger-pointing, self-righteous grandstanding, and downright meanness has increased both on campus and in the public square as these efforts escalate. Civil discourse and a willingness to listen when others speak continue to decline as these measures are implemented.

To build capacity for appreciation across faith-lines and to cultivate a vision that values diversity as an asset, we need, instead, to provide our students with the skills that will bridge differences and cultivate positive relationships across religious divides. Speed-faithing can help cultivate this climate of appreciation and empathy because it teaches students to share authentically, to listen appreciatively, and to identify common values across boundaries of religious difference. It can help because it cultivates the kind of dialogue necessary to transform stereotypes and misperceptions as it builds connections among real individuals with real life histories and real “worthy dreams.”

I have found speed-faithing to be a valuable tool—both within and beyond the classroom. It is a tool that I have used to encourage dialogue and to build bridges of empathy and connection among participants. It is only one tool, and it only serves to open dialogue that must be supported and nurtured with other pedagogies. But, it is a good beginning as we—collectively—work to construct the bridges of cooperation and common concern that may just inoculate our campuses against the rising waters of intolerance that threaten to drown and destroy civility on campus.

Resources

Astin, Alexander W., Helen S. Astin, and Jennifer A. Lindholm. 2010. Cultivating the Spirit: How College Can Enhance Students’ Inner Lives. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Glass-Coffin, Bonnie. 2016. “Building Capacity and Transforming Lives: Anthropology Undergraduates and Religious Campus-Climate Research on a Public University Campus.” Annals of Anthropological Practice. 40 (2): 258–269.

Jacobsen, Douglas, and Rhonda Hustedt Jacobsen. 2012. No Longer Invisible: Religion in University Education. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Parks, Sharon Daloz. 2011. Big Questions, Worthy Dreams: Mentoring Emerging Adults in Their Search for Meaning, Purpose and Faith, 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Patel, Eboo. 2016. Interfaith Leadership: a Primer. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Bonnie Glass-Coffin is professor of anthropology and affiliate professor of religious studies at Utah State University. She believes in providing spaces for students to explore the biggest questions in their lives as part of their university experience. In 2014, she founded and currently directs the USU Interfaith Initiative, which works to create positive and meaningful interaction among people who orient around religion differently. She has published three books, dozens of scholarly articles on topics ranging from gender and shamanic ritual and practice in Latin America and the United States to interfaith cooperation on American university campuses. She has developed and offers faculty/staff and student trainings in interfaith cooperation, both at USU and for employees from schools throughout the Intermountain West. In early 2017, she completed an MDiv in Interfaith and Inter-spiritual Studies from All Paths Divinity School in Los Angeles, California. She can be contacted at bonnie.glasscoffin@usu.edu or http://interfaith.usu.edu.

Bonnie Glass-Coffin is professor of anthropology and affiliate professor of religious studies at Utah State University. She believes in providing spaces for students to explore the biggest questions in their lives as part of their university experience. In 2014, she founded and currently directs the USU Interfaith Initiative, which works to create positive and meaningful interaction among people who orient around religion differently. She has published three books, dozens of scholarly articles on topics ranging from gender and shamanic ritual and practice in Latin America and the United States to interfaith cooperation on American university campuses. She has developed and offers faculty/staff and student trainings in interfaith cooperation, both at USU and for employees from schools throughout the Intermountain West. In early 2017, she completed an MDiv in Interfaith and Inter-spiritual Studies from All Paths Divinity School in Los Angeles, California. She can be contacted at bonnie.glasscoffin@usu.edu or http://interfaith.usu.edu.