Managing Crisis and Conflict in the Religious Studies Classroom

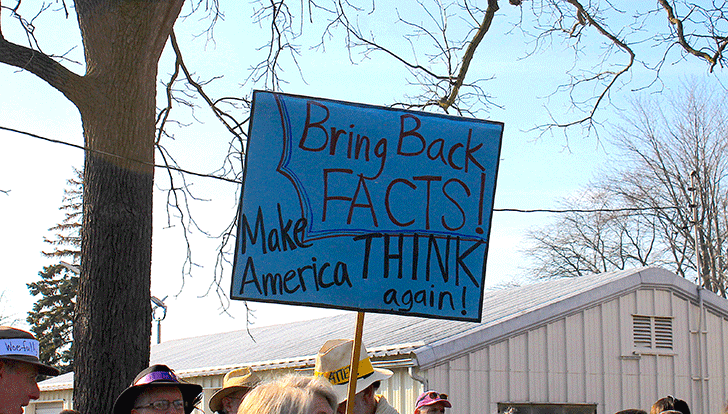

Photo: Women’s March in Seneca Falls, NY, on Jan 21, 2017, by Lindy Glennon.

A Story Chosen

Religious studies scholars are uniquely positioned to discuss the election of Donald Trump and its aftermath. The nature of our topic matter requires that we know how to discuss controversial topics in the classroom. People care as passionately about their religious identities as they do about their political affiliations. Techniques and approaches that invite exchange among Roman Catholic, Hindu, Muslim, Baptist, and Wiccan students most often work to do the same when supporters of Bernie, Donald, and Hillary are in the room. The most difficult point of discernment, however, is to figure out when those techniques are likely to fail and to know what to do instead.

I faced this very question on the first day that students in my course, “Black: From Africa to Hip-Hop,” met after Donald Trump’s election. In this introductory course, we had just finished a week on Islam in North America and were preparing to turn our attention to an examination of religious themes in contemporary hip-hop. Up to this point, classroom discussions had been robust, animated, and energetic—but never really polarized. Of course, the breadth of opinions in the classroom reflected Montana’s electorate in tenor and tone. In comparison to many East Coast universities, for example, students expressed politically conservative views more often, libertarian perspectives popped up more frequently, and those on either end of the spectrum sounded generally less strident.

So, when I walked into the classroom on the Thursday after the election, I planned to remind students of the values they had agreed to uphold on the very first day that we met. Values like mutual respect, avoiding stereotypes, and grounding comments in evidence and first-hand experience have created productive spaces in my religious studies classes. I thought that those values would transfer over to a discussion about what the Trump election would mean for the Islamic community, the hip-hop world, and African American religious practitioners—the topics we had and would soon address.

I knew immediately, however, that this time those values would not suffice.

At least one student was quietly weeping. Another radiated righteous ire. One cluster of students was uncharacteristically quiet but also clearly elated. Some of my most stalwart and dependable students hadn’t even shown up. Others looked frightened, confused, smug, or defeated. I cannot remember a time when I encountered such an array of emotions so visibly displayed.

So I changed my plan. Rather than invite discussion amid such raw emotion, I decided to tell a story. I described another time when the country was intensely divided, when the lives of women and people of color were being publicly threatened, and when hate groups were on the rise. I described the murder of the young white seminary student and activist Jonathan Daniels in 1965, his heroic sacrifice to save the life of the then seventeen-year-old voter registration activist and black Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) member Ruby Sales, and the subsequent decision by SNCC activists to continue uncowed, forthright, and direct in their political efforts.

I told the story and turned to the work of the day.

Upon hearing me describe my choice to tell this story rather than encourage discussion, a colleague asked me, “But weren’t you really only speaking to a certain set of your students? What about those who were happy about the election’s outcome? How did your story support them?”

She had a point.

My story about Jonathan Daniels and Ruby Sales did speak most powerfully to the students who were feeling devastated, angry, or afraid at that moment. I made a pedagogical decision to offer them solace. They were, after all, the ones who were most at risk. Within forty-eight hours of the election, instances of racial harassment, bullying, and hate crimes had spiked. One of my students, an African American bisexual woman, would go on to post a deeply troubling account of an instance of racial harassment that required her to relocate for her safety.

At the same time, the story I told did no harm to the students excited about the Trump election. I made no direct connections, offered no commentary, placed no blame on any student in the room. As in the case of all good storytelling, it is the story itself that carries the weight, that allows those who hear it to interpret it for themselves. It is why a story seemed the best possible choice in a moment fraught with such intense emotion.

Dealing with Crisis

Storytelling is not the only option for dealing constructively with teaching religion in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election. Many principles honed through the study and teaching of religion do transfer and prove effective.

Central to my overall pedagogical approach is a commitment to embracing crisis and using it to further students’ intellectual growth. For example, on the first day of “Voodoo, Muslim, Church: Black Religion,” I carry a large stone above my head, thump it down in the center of the room, and declare, “This is a religious object. Respond.” I allow the crisis of uncertainty, confusion, and frustration to build without giving any additional direction until—inevitably—someone breaks this silence and explains why they do—or do not—think the stone is a religious object. It is often the best, most rigorous and lively discussion of the semester.

In this instance I create crisis through my refusal to expound on my initial declaration. An essential part of the exercise is that I then remain quiet but fully attentive, centered, and relaxed as the students struggle to figure out what they should do.

In essence, I aim to model a “nonanxious presence” in the midst of conflict and disagreement. Mediators have long observed that one of the best ways to de-escalate conflict is simply to remain calm when it erupts. Having learned that conflict is natural, normal, and neutral, I am better able to de-personalize the crisis, remain focused, and look for ways to invite students into deeper learning through conflict rather than in spite of it.

Learning to use conflict rather than avoid it is the most essential skill instructors can acquire to deepen student engagement. Instructors who can remain relaxed, focused, and comfortable when crisis erupts—whether from planned or spontaneous classroom dynamics—have the best chance of ushering students to a new, if unfamiliar, learning space. It is never my job to make the discomfort or crisis dissipate. In the midst of such uncertainty some of the best learning takes place.

At the same time, within the bounds of my physical and intellectual ability, it is my job to ensure the safety of my students. As such, I will intervene if anyone engages in verbal attacks. I will remind students of the values of mutual respect that we establish at the beginning of class. I will model an equitable means of response to and engagement with one’s opponents.

I also bring into the classroom techniques and methods that have emerged from the disciplines of mediation, conflict resolution, and conflict transformation. In my class, “Prayer and Civil Rights,” I regularly set up a debate early on in the course about the efficacy of violence and nonviolence during the civil rights movement. Several weeks later, I then use a fishbowl exercise on the same topic in which participants have to listen to an opposing viewpoint, restate that person’s view to their satisfaction, and only then explain their view. The rest of the class sits in a circle around the interlocutors and may join the conversation by listening, restating, and voicing their perspectives. Students invariably express amazement at how much more productive the conversation is when they are required to focus on listening rather than on preparing a rejoinder.

But I have also learned that crisis requires clear-eyed judgment about when to cut off, limit, or redirect heated conversation. In one of my introductory courses, I had given extra credit for students to attend a talk by Patrice Cullors, one of the founders of the Black Lives Matter movement. The morning after her talk, I wanted to give students the opportunity to discuss their reaction to her lecture, but I knew from mid-course evaluations that some students felt I did not allow “the other side” of the African American religious experience into my classes. In short, they felt that I censored the views of those white supremacist groups who have coalesced under the “alt-right” label.

Given that I am as committed to encouraging debate as I am to ensuring that racist stereotypes are not legitimized, I chose to narrowly frame our discussion of the Cullors talk. Rather than debate the specific content of Cullors’s speech, I simply asked students to comment on what they had learned by listening to her. This prompt invited multiple perspectives but focused the conversation on sharing personal experiences rather than debating truth claims. While debates are essential in an era when many disregard factual data, historical proofs, and rational argument, great care, attention, and forethought are needed to make debates productive. Debate for debate’s sake alone seldom enhances student learning.

A Changing Context

We teach in the midst of a number of contexts. First, each group of students brings its own personality, level of engagement, and preparation to the classroom. Likewise, any given institution cycles through financial, cultural, and structural challenges that influence the tenor and complexion of the learning environment. Larger national and statewide trends likewise shape professor-student interactions.

The question that I have been mulling over for the past number of months is, “What specifically has changed with the election of Donald Trump?” We already have credible evidence that overt acts of racism, sexism, and anti-Semitism have proliferated. Issues of cabinet appointments, policy pronouncements, and budget appropriations aside, we have also seen an administration committed to undercutting public education at all levels. The political divides in our nation have hardened and grown wider in the aftermath of this election as well.

But more importantly, faculty’s ability to pursue academic inquiry without political interference has come under attack. Whether or not, as Cornel West contends, the outcome of the election was an indictment of the academy, at least three state legislatures have struck out against tenure policies at public institutions of higher learning. Those who initiated Professor Watchlist to target over a hundred professors—myself included—for our “radical” teaching agenda have met with the Trump transition team. The idea of thinking deeply, carefully, and thoughtfully about controversial issues such as religious identity appears to have fallen out of favor among the general public. In an age of listicles, research-based writing—whether in popular or scholarly form—reaches the smallest of audiences.

That larger political context has begun to shape classroom instruction. But, I would contend, we who teach in higher education have a responsibility to respond intelligently, deliberately, and directly to those who would curtail rational argument in favor of bombast and prolixity. Our classes on religion can be spaces where we not only model rationale discourse, but where we require students to practice the same. We can foster spaces that counter rhetorical bullying, invite respectful disagreement, and value research, scholarship, and study.

Religious studies scholars have a unique role to play in the shaping of our national future. Although it may be a small role and one not always recognized, it is no less essential. By making thoughtful decisions, becoming comfortable with crisis and conflict, employing proven techniques to foster conversation between adversaries, and grounding all we do in the knowledge we help create, we can be part of creating a future in which we in the academy—and especially those of us who study and teach about religion—will be celebrated for the role we played in nurturing democracy at a point when it was most threatened.

Resources

Dutta, Urmitapa, Teresa Shroll, Jennifer Engelsen, Sadie Prickett, Laura Hajjar, and Jamila Green. 2016. “The ‘Messiness’ of Teaching/LearningSocial (In)Justice: Performing a Pedagogy of Discomfort.” Qualitative Inquiry, 22 (5): 345–352.

Evans, David, and Tobin Miller Shearer. 2017. “A Principled Pedagogy for Religious Educators.” Religious Education. 112 (1): 7–18.

Hunter, Amy A., and Matthew D. Davis. 2013. “Revolutionary Reforestation and White Privilege in a Critical Race Doctoral Program.” In Social Justice Issues and Racism in the College Classroom: Perspectives from Different Voices, edited by Patricia G. Boyer and Dannielle Joy Davis, 113–131. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Kisfalvi, Veronika, and David Oliver. 2015. “Creating and Maintaining a Safe Space in Experiential Learning.” Journal of Management Education 39 (6): 713–740.

Leonardo, Zeus, and Ronald K. Porter. 2010. “Pedagogy of Fear: Toward a Fanonian Theory of ‘Safety’ in Race Dialogue.” Race Ethnicity and Education 13 (2): 139–157.

Paris, Jenell William, and Kristin Schoon. (2007). “Antiracism, Pedagogy, and the Development of Affirmative White Identities Among Evangelical College Students.” Christian Scholar's Review 36 (3): 285–301.

Radford, Mike. 2006. “Researching classrooms: Complexity and Chaos.” British Educational Research Journal 32 (2): 177–190.

Tobin Miller Shearer is an associate professor of history and director of African American studies at the University of Montana. He holds a dual-PhD in history and religious studies from Northwestern University and teaches courses on African American religion, North American religion, and religion in the civil rights movement. He has written widely on Mennonites, whiteness, childhood, and the broad theme of race and religion. His most recent book is Two Weeks Every Summer: Fresh Air Children and the Problem of Race in America (Cornell University Press, 2017). His next book project is entitled Devout Demonstrators: Religious Resources and Protest Movements.

Tobin Miller Shearer is an associate professor of history and director of African American studies at the University of Montana. He holds a dual-PhD in history and religious studies from Northwestern University and teaches courses on African American religion, North American religion, and religion in the civil rights movement. He has written widely on Mennonites, whiteness, childhood, and the broad theme of race and religion. His most recent book is Two Weeks Every Summer: Fresh Air Children and the Problem of Race in America (Cornell University Press, 2017). His next book project is entitled Devout Demonstrators: Religious Resources and Protest Movements.