Theological Education at a Crossroads: Wrestling with Emerging Cultural Paradigms

Every now and then we need to ask again what it means to educate theologically. It is an opportunity to assess what we are doing while envisioning fresh approaches to advance this noble task creatively and effectively. How we answer this question has profound implications for faith communities, theological institutions, and even the field of theology itself. Theological educators must rise to the occasion to imagine what it means to form an emerging generation of theological scholars, pastoral leaders, and educated Christians in light of the various transitions—cultural, social, and ecclesial—that shape the current religious landscape in the United States of America.

In this article, I offer a reflection on what it means to educate theologically by drawing on my own experience and interest in how the relationship between theology and culture shapes educational processes. I join this conversation as a theologian, deeply rooted in the Roman Catholic tradition and the US Hispanic cultural experience, intentionally teaching theology in an institution that trains women and men for ministerial service and academic life.

Theological Education: A Noble Task

I understand Christian theological education to be the art of facilitating, within the horizon of the Christian tradition, the process of dynamically discerning what it means to be human and a believer in history as well as the practical implications of such discernment for the person, society, and the church. As such, theological education is a noble task. Its nobility is rooted not only in the ultimate subject of theological reflection (i.e., the mystery of God discerned in the here and now of our shared historical existence), but also in the people who are involved in it: flesh-and-blood women and men with real questions, hopes, and concerns, searching for meaning in the everyday, working to build a better society.

When intentionally done by a community of believers in the context of the university or the seminary, in the congregation or in non-ecclesial spaces, theological education is ultimately an exercise of a ministry: the ministry of the Word. Theological education does not occur in a vacuum, nor is it isolated from the sociohistorical forces that shape everyday life. To educate theologically, therefore, has clear spiritual, social, ethical, and even political implications that we cannot ignore or escape. Structures come and go, as do theologians, administrators, ministers, and even congregations. Nonetheless, there will always be a need to imagine how to best educate theologically a new generation of believers.

Between the Old and the New

Transitions are not easy. It is natural to hold on to what we know and to become suspect of anything that challenges our status quo. When individuals or groups have worked hard to achieve certain goals, they will rightly share a strong sense of ownership that deserves affirmation. However, even as we honor the good work that has been done, it is imperative that we listen to new voices: those who have recently arrived to our country, our schools, and our churches, as well as those here for a long time who been muted by a variety of forces, but who are increasingly claiming their right to have their voice heard and taken seriously. Christian theological education in the United States is in many ways at a crossroads between what has been and what can be. These realities are not mutually exclusive. In fact, what can be builds upon what has been, and what has been encounters a new chance to be—in distinct ways—in what is new.

Christian churches and institutions in our country are undergoing significant transformations in terms of demographics, culture, and even practical commitments. In response, the educational bodies in charge of preparing the agents to lead them and the scholars dedicated to study their traditions are exploring fresher ways of doing theology and new ways of theologically educating emerging generations. Our society is changing significantly. We can no longer take religion for granted, particularly as the intensifying forces of pluralism and secularization challenge us to prepare our students for new conversations.

If they are to be faithful to the communities and institutions with which they claim to be in close relationship, institutions dedicated to theological education must develop curricula that empowers Christians to engage the vital questions and concerns of our day. The diversity of our communities raises important questions that have received little attention in many of our institutions. Now is the time to be honest with ourselves as theological educators and with our students, and to take seriously issues of race, culture, violence, machismo, eurocentrism, inequality, clericalism, polarization, and more.

To address the urgent questions of our day, we need pedagogies that go beyond traditional lectures and class conversations that often seem distant from the concerns and hopes of people at the grassroots. How we educate ministers and scholars shapes the way they exercise their ministry and engage their scholarship. New technology, social media, sophisticated means of communication, and access to digital platforms that provide almost unlimited resources for the study of theology and religion invite us to ask urgent questions: Is this a time to reimagine the traditional seminary and theologate? If so, what would be appropriate and effective models to achieve our aims? Is it a time to reimagine the role of the theological educator? Is it a time to reimagine how we credential the new generations of pastoral leaders and academics? No question should be off the table.

Modes of Theological Reflection and Theological Education in a Diverse Church

For more than half a century, the field of Christian theology has witnessed the emergence of multiple discourses building on the particularity of experience and context. These discourses continue to address the perennial questions of theology: theodicy, salvation, revelation, cosmology, etc. They do this acknowledging that ultimately all theology begins as an exercise of local reflection—including those discourses that do not name their particularity and often pass as normative theology. It is by affirming their particularity that these contextual discourses can claim a universal voice. Contextual discourses have benefitted significantly from the development of new methods as well as the engagement of a wide range of fields of knowledge beyond philosophy and Scripture studies. And many of these discourses intentionally engage the particular communities out of which their best insights emerge. This work is not centered merely on studying the texts of these communities or by talking about them, but by living with them and listening to their voices.

The question then emerges: has theological education kept up with these developments? I am afraid that the honest answer is, not always. If adding an article or a chapter written by a “contextual theologian” or a “feminist thinker” to the syllabus is meant to engage the rich diversity of theological reflection in our day, then the answer is no. If hiring a Black or Latino/a or Asian or Native American scholar and expecting that one person to address all matters related to contextuality, race, culture, ministry to the people she/he supposedly represents, and the particular histories of all minoritized groups, then the answer is no. If accepting only a small group of “minority” students into a graduate program to fulfill an established quota, particularly knowing that those students come from large populations that give life to a given denomination, then the answer is no. If our theological formation programs conclude that they need to close or become something else because the traditional students are not there anymore while simultaneously ignoring alternative models that may work better for new populations, then the answer is no.

Theological education must incorporate the methods, sources, conversations, and results emerging from contextual theological discourses into the pedagogies used in our educational settings. At the same time, it should challenge theologians and educators who belong to any dominant group to acknowledge their own particularity. This requires theological educators to intentionally draw from contemporary theories of education and related fields that take key categories such as culture, race, anti-bias curriculum, interculturality, etc., into consideration to educate theologically in new ways—ways that will take theological education in the 21st century a step forward toward a more robust response to rapidly changing times and institutional configurations. I believe that exposing our theology students, congregations, and believers who participate in any form of theological education to pedagogies, methods, and resources that acknowledge the value of diversity, context, culture, and experience, will change the ways in which we do theology in the United States.

Dynamic Tensions that Need to Be Engaged

As we reflect on theological education in a time of emerging cultural paradigms, I find it helpful to think in terms of dynamic tensions. I use this term intentionally, aware that as we educate theologically, we encounter realities that escape homogenization or standardization. These dialectics are not necessarily opposite. And by the nature of what they signify, each resists being collapsed into the other. Dynamic tensions elude simplistic solutions. The existence of a dynamic tension is in itself a source of energy, life, and creativity. They do not necessarily demand synthesis. Distinct realities in any relationship of dynamic tensions should be affirmed in their particularity while imagining how theological education can better respond to them. Taking seriously these tensions requires substantial work and investment. It is work that can be exhausting. It may even demand a new kind of leader able to wrestle with ambiguity, sometimes even to dwell in it.

In the present moment, I note four dominant dynamic tensions informed by my own survey of the current terrain:

First, there is a dynamic tension between what might be called a dominant establishment and an emerging force of minoritized voices, usually people of color and other underrepresented groups within churches and society. Even as Christian congregations throughout the country continue to go through profound transformations in terms of race, ethnicity, and culture, the work of formal theological education continues to be done primarily by scholars of one race. During the academic year 2015–16, 77% of all full-time faculty, male and female, in schools that are part of the Association of Theological Schools (ATS) were reported to be non-Hispanic White. The gender gap is also appalling: during the same academic year, in the same schools, 75.8% of all full-time faculty were reported to be male.

Second, there is an emerging dynamic tension between a generation of faculty and administrators who remain in our schools and those who are newly arriving. Put plainly: as faculty and administrators of color gradually assume responsibility for theological schools and seminaries, they usually succeed White male predecessors. The work of those who arrive is often met with a hermeneutic of suspicion that questions their viability, identity, and even the worth of the credentials by those who remain. In the process of these kinds of transitions, deep differences in the definitions of theological education often emerge without explicit acknowledgment.

Third, the classic dynamic tension between “theory” and “praxis” takes on new forms from the perspective of theological education. One manifestation of this tension is a growing gap between research schools and institutions that train pastoral leaders for ministry. This gap significantly influences not only the student recruitment process, but also the kind of curricula designed to train them, ultimately affecting how we prepare them to meet the needs of a society and a church in flux. Sometimes this tension is present even within a single institution.

Fourth, a fast-growing dynamic tension is one between previous ways of delivering theological education and emerging models. Should theological education continue to be delivered in traditional institutions with traditional faculty on site and traditional curricula? Should it embrace online and other forms of (nontraditional) education that drive learning patterns and educational needs among new generations of Christians? A both/and approach often seems reasonable to theological educators; but are we having the kind of deep conversations to which this tension invites us? This dynamic tension calls for serious reflection on matters of accessibility, technological literacy, sociocultural disparities associated with the use of technology and social media, and more. It also invites reflection on the danger of the ongoing potential for neocolonialist practices as wealthier institutions, churches, and nations (like ours) own and control the means of delivery and thus become the de facto arbiters of content and method.

The ultimate goal, I think, is not to invert orders or to subsume the elements within each set of tensions, but to imagine how, through theological education, we can contribute to building stronger faith communities, a more relevant academy, and a more just society where everyone can live with dignity.

Hosffman Ospino is a professor of theology and religious education at Boston College School of Theology and Ministry where he is also the director of graduate programs in Hispanic ministry. He has authored and coedited eight books and published more than sixty articles in academic journals and public venues. His most recent book is the edited collection, Hispanic Ministry in the 21st Century: Urgent Matters (Convivium Press, 2016). Ospino served as the principal investigator for the National Study of Catholic Parishes with Hispanic Ministry (Boston College, 2014) and co-investigator for the National Survey of Catholic Schools Serving Hispanic Families (Boston College, 2016). He presently serves as an officer of the Academy of Catholic Hispanic Theologians of the United States (ACHTUS) and is on the board of directors of the National Catholic Educational Association (NCEA).

Hosffman Ospino is a professor of theology and religious education at Boston College School of Theology and Ministry where he is also the director of graduate programs in Hispanic ministry. He has authored and coedited eight books and published more than sixty articles in academic journals and public venues. His most recent book is the edited collection, Hispanic Ministry in the 21st Century: Urgent Matters (Convivium Press, 2016). Ospino served as the principal investigator for the National Study of Catholic Parishes with Hispanic Ministry (Boston College, 2014) and co-investigator for the National Survey of Catholic Schools Serving Hispanic Families (Boston College, 2016). He presently serves as an officer of the Academy of Catholic Hispanic Theologians of the United States (ACHTUS) and is on the board of directors of the National Catholic Educational Association (NCEA).

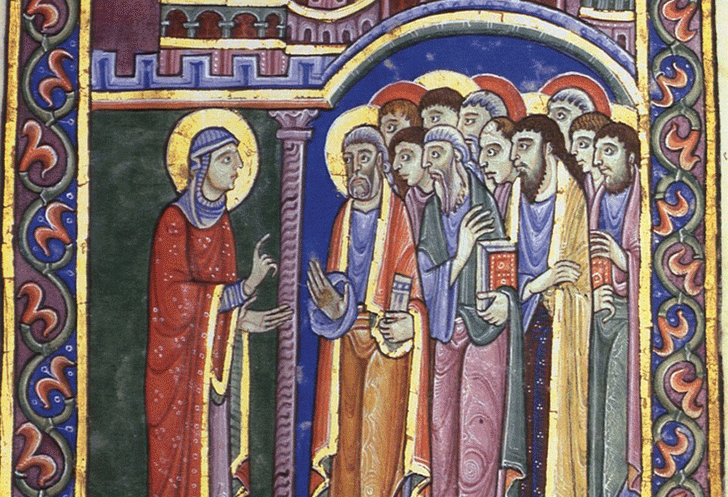

Header image: Mary Magdalene announcing the Resurrection to the Apostles, St. Albans Psalter, 12th century