Teaching Demonology, Possession, and Exorcism in Texas

Introduction

I am an assistant professor of religious studies at Texas State, a rapidly growing state university in San Marcos, Texas. Texas State offers a minor in religious studies and is currently creating a major. I was hired to help build the new major and generate student interest in religious studies. Specifically, I was encouraged to teach a class through the Texas State Honors College that would “get butts in seats” and show why religious studies is a fascinating field. I had just finished editing an encyclopedia called Spirit Possession around the World for ABC-CLIO and this seemed like the perfect basis for a high-interest course. So I designed a course called “Demonology, Possession, and Exorcism” that was offered in the fall of 2015. The course was popular enough that the Honor’s College asked me to teach it again in the spring of 2017.

“Spooky” Topics in the Classroom

Exorcism is a serious subject in Texas. Texas State’s library owns an autographed copy of Pigs in the Parlor, a seminal text in the deliverance ministry movement that formed in the 1970s. The authors, Frank and Ida Mae Hammond, studied theology at Southwestern Baptist Seminary in Fort Worth. The first day of class we watch cellphone footage of some young men allegedly performing an exorcism in an Austin Starbucks. Several students said the scene didn’t look improbable at all—that they had seen exorcisms like this performed in the small Texas towns where they grew up. Some students told me their parents had concerns about them taking the class. I asked them whether their parents were worried they would get possessed or whether they would stop believing in demons. Their answer was both: they might stop believing in demons and then get possessed.

Even though exorcism seems so ubiquitous as to be banal, teaching a class about it at a university remains somehow scandalous. (In fact, when word got out I was teaching this course, I was asked to appear on the paranormal radio show Coast to Coast AM). Religious studies has historically regarded exorcism or anything that smacks of the “the paranormal” as slightly embarrassing––especially where these beliefs and practices concern contemporary Americans instead of, say, far off indigenous cultures or medieval Europeans. This unstated “two-tier model of religion” has come under increasing scrutiny from the academy, but it still shapes the way undergraduate courses are organized. Spirit possession or similarly “spooky” topics are still much more likely to be discussed in the anthropology department than in religious studies.

While spooky topics help boost enrollment, they come with their own set of challenges. The single greatest obstacle I’ve encountered is that students find the material interesting but have difficulty imagining what it would look like to approach it in a rigorous and critical fashion. This problem takes several forms. Some students assume that because the topic is fun, the course must be easy. These students may be disappointed when, for example, they submit a shallow analysis of their favorite horror movie as a research paper and receive a poor grade. This isn’t simply laziness: These students often don’t understand that their peers are getting higher grades because they are doing better research and producing more rigorous work. Other students mistake simple skepticism for analysis. They regard the thesis that demons are not real as the end of analysis instead of the beginning.

Finally, I have noticed that there is a flip side to the two-tier model of religion: Some students seem to assume that because these topics are more frequently discussed on internet forums and YouTube videos than in college classrooms, that professors are merely tourists to this material. There is a certain type of student I call “a lore master” (or a “lore mistress”). The lore master has typically invested a lot of time learning about the paranormal through popular media and is proud of their knowledge. The lore master is often adept at, for example, listing various Goetic demons and their powers, but not yet good at contextualizing this data. Rather than regarding these demons as mythic personages with interesting variations across cultures and centuries, they understand them as data that is universal and self-evident, like the periodic table. A lore master may feel slighted when their favorite fact or story is treated as a mere datum in a much larger pattern of beliefs and cultural practices. At worst, the lore master may come to the class expecting to be praised for the knowledge they have already attained and feel resentful when they are asked to rethink this knowledge within a larger context or from a new perspective. In many ways, the lore master resembles a familiar problem in teaching biblical literature, where students who have studied the Bible from a confessional perspective want college credit but are resistant to learning about historical approaches to their sacred text.

Teaching about Demons

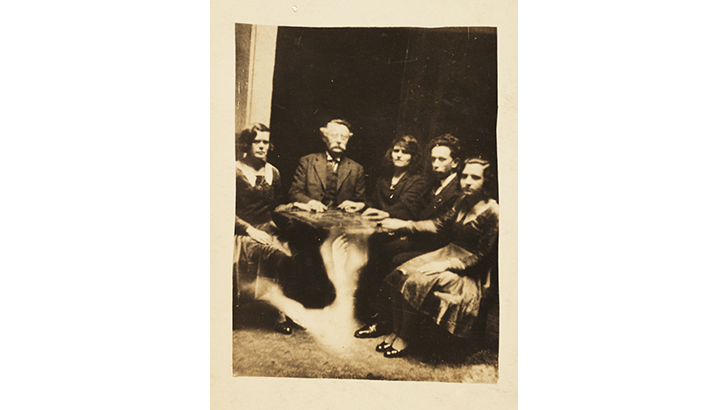

Most cultures on Earth have some tradition of spirit possession, so the amount of material that could be included in a course called “Demonology, Possession, and Exorcism” borders on the infinite. It is a struggle to show students the breadth of the material and the theoretical lenses for approaching it while still giving the course some coherent structure. The course focuses primarily on the history of Western tradition, moving from the ancient Near East, through the Bible and apocrypha, to early modern Europe. The second half the course looks at the Spiritualist movement, medical models of spirit possession beginning in the 19th century, and the resurgence of Catholic exorcism and deliverance ministry in the 1970s. The last week considers Ufology and conspiracy theories as forms of contemporary demonology. Along the way, I found ways to insert comparative cases from Hinduism, Islam, Vodou, and Native American religion.

To add more breadth, I tried an exercise in which each student was given a recent news article on possession. They were then asked to give analysis of what they thought was happening and present it to the class. I deliberately selected cases from as many continents and religious traditions as possible. This effectively created over twenty miniature case studies. I emphasized that the point of doing this was both to “survey the territory” and also to begin thinking of topics for research papers. I have also tried to select readings that are accessible but allow students to approach this material from multiple angles. I have assigned selections from Carl Sagan to introduce basic epistemology, Erika Bourguignon’s work on spirit possession for anthropology, Christopher Bader’s et al.’s (2011) Paranormal America for sociological approaches, David Frankfurter’s (2006) Evil Incarnate for discourse analysis, Freud’s essay on demonic possession for psychoanalytical approaches, and the work of Richard Noll for psychiatric approaches.

Assessment is built around class discussion and a research paper. Class participation is worth a whopping 30% of their grade. Each class begins with a short lecture to supplement the reading material. Then I put some discussion questions on the board. We move in a circle and each student is required to say something of substance about the reading. Their comments do not have to relate to one of my discussion questions, but the questions help the students to think of something to say. Although we move in a sequence, students do not have to “wait their turn” to talk. They are encouraged to raise their hand and piggyback or respond to someone else’s point. The advantage of this method is that every student speaks at least once. Students who have not done the reading can fake their way through discussion, but they can’t arrive to class with the hope of keeping their head down and letting other people talk. As we talk, I make a note of students who have specific passages from the text they want to talk about. If students sheepishly confess they have not done the reading, I note that too. Halfway through the semester I give students a preliminary participation grade with notes about how I would like them to improve.

I believe in student research papers. I think they hone skills students need for the job market and a life well lived and also give them a sense of ownership over their learning. Unfortunately, even in the Honors College, I get students with no idea how to write a research paper. They never learned these skills in high school or, worse, they left high school thinking a Google search qualifies as college-level research. I invest a lot of time and energy into giving students the training and guidance they need to write a great research paper. We take a field trip to meet our librarian, who shows students how to use databases, interlibrary loan, and other services. (Many students do not know how to check out a library book.) We also take a field trip to the writing center and discuss how to make an appointment. I require a prospectus with an annotated bibliography, an outline, a draft, and a final product. Combined, these assignments are worth 70% of the student’s grade. Having these benchmarks makes it impossible for students to procrastinate. It also allows me to guide their research as it develops. Thinking of a good question for their prospectus is the single most important part of the process.

Additionally, I offer extra credit assignments to encourage students to physically enter the library and engage with its resources. Students can take a “shelfie” (a cellphone “selfie” photo taken in the library stacks), bring a library book to class, or bring an interlibrary loan book to class. Each of these small assignments is worth an extra point on their research paper grade. I also offer students a point if they take a picture of themselves holding The Compendium Maleficarum. Texas State owns a copy of this text, and giving students an incentive to track it down opens their eyes to the kind of resources available to them. I created these assignments when I realized some students were unwilling to use resources if they couldn’t access them online.

Most importantly, I emphasize to students that professors are professional researchers and that they are practicing doing what we do. I explain that when I edit a peer-reviewed journal, I am essentially giving the same kind of critique and guidance that I do with their papers. I also encourage students to either submit their work to journals or present it at research conferences. There are journals and conferences that seek undergraduate research. Few students actually pursue this, but talking about it conveys that their analysis is significant and meaningful and not just an arbitrary exercise to get a grade. Two students from the demonology course have gone on to produce honors theses with me as their supervisor.

Wrestling with Demons

The biggest challenge I have teaching a demonology course is getting students to find a balance between credulousness and smugness. Finding some balance between the hermeneutics of respect and the hermeneutics of suspicion is a problem for all of religious studies, and there is hardly a consensus among religion scholars about where this line should be drawn. But this problem is exacerbated when looking at claims of extraordinary experiences.

I often encounter the attitude that anyone claiming to experience spirit possession is either mentally ill or lying and that anyone who fails to understand that is simply unintelligent. This view is often accompanied by a certain self-congratulatory attitude. One thing I try to get students to see is that even if demons are not real, a dismissive attitude makes it hard to see the intricate social functions that possession and exorcism serve or interpret experiences of spirit possession.

On the other hand, some students exhibit an alarming lack of suspicion. While discussing The Demonologists, a book about Ed and Lorraine Warren, one student expressed that all the stories of the Warrens’ adventures seemed plausible until we began discussing them in class. I added Carl Sagan to the course partly to give students a basic tool kit for assessing extraordinary claims. I have also found myself telling students that religious truth claims should not be exempt from critical thinking. As researchers, we shouldn’t refrain from questioning claims of spirit possession just because they are part of someone’s religion.

In their research papers, I often advise students to avoid making claims about demons that are difficult to prove so that they can devote more space to proving their thesis. Most papers don't actually need to prove that demons categorically do not exist. Conversely, if a student’s paper is dependent on proving the literal existence of demons, I usually advise them that they do not have space to prove such a claim in an eight-to-ten-page paper.

Analyzing extraordinary experiences like spirit possession is a great entrée into theory and method in religious studies. In fact, the two-tier model of religion, which has subtly influenced undergraduate introductory religion courses, seems designed to push these theoretical conundrums aside in favor of the “world religion” model. Of course, basic religious literacy is an important part of a college education, but no one can really call herself a religion scholar until they have wrestled with demons.

Resources

Bader, Christopher David, Frederick Carson Mencken, and Joe Baker. 2010. Paranormal America: Ghost Encounters, UFO Sightings, Bigfoot Hunts, and Other Curiosities in Religion and Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Bourguignon, Erika. Possession. 1991. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press.

Frankfurter, David. 2008. Evil Incarnate: Rumors of Demonic Conspiracy and Satanic Abuse in History. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Freud, Sigmund. 1961. “A Seventeenth-Century Demonological Neurosis.” In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud XIX (72–105). London: The Hogarth Press.

Noll, Richard. 1993. “Exorcism and Possession: The Clash of Worldviews and the Hubris of Psychiatry,” Dissociation 6, no. 4: 250–253.

Sagan, Carl. 2013. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. New York: Random House.

Joseph Laycock is an assistant professor of religious studies at Texas State University. He researches American religious history and new religious movements. His most recent book is Dangerous Games: What the Moral Panic over Role-Playing Games Says About Play, Religion, and Imagined Worlds (University of California Press, 2015).

Joseph Laycock is an assistant professor of religious studies at Texas State University. He researches American religious history and new religious movements. His most recent book is Dangerous Games: What the Moral Panic over Role-Playing Games Says About Play, Religion, and Imagined Worlds (University of California Press, 2015).