Engaging the Telos and Sharing Tales of Theological Education

I share here three tales that shape and express how I have come to make sense of a telos of theological education that forms, informs, and transforms the people of God into faithful embodiments of the peace, grace, and joy of the Gospel. The first is the story of how my parents influenced my own trajectory into theological education. The second describes my work as dean of a grassroots theological learning community seeking the peace and flourishing of the city. And the third story shares lessons learned from my research on racial/ethnic minority women leaders in global theological education. Together, these three experiences have helped me discover a theological education that is responsive, relevant, and practice-based for all of life.

I. My Story

The child of immigrant parents from Hong Kong, I emigrated not from Asia, but from Europe. My father was an electrical engineer in the United Kingdom, but in the early 1980s, an American defense firm sponsored him and our family to come to the United States. My parents were both missionaries impacted by the fervor of student campus movements in Hong Kong in the 1950s and 1960s. They founded a broadcasting ministry to evangelize to Chinese in London, and brought the ministry with them when they made a new home in the suburbs of New York City.

By day, my father worked as an engineer, but by night, he and my mother would be in the basement studio, recording evangelistic and discipleship programs in ten or so Chinese dialects on cassette tapes with pastors, mission workers, and missionaries from all over the world. Created for those who could not attend church on Sundays, the tapes were broadcast over the public-address systems of garment factories, distributed to restaurant workers, and given to grandparents to listen in their native language. Today, my parents continue this ministry in Asia using digital audio players, short-wave radio, and Internet broadcast. Although they have been on the frontlines of ministry, they never had time for a formal theological education. My mother tried twice, but was unable to complete a doctoral program in missiology.

When I attended seminary with my husband Tony during our second year of marriage, I did not go with the intention of seeking ordination, but with the aim of understanding how my faith impacted life in its entirety. I wanted to know how it shaped and expressed who I was vocationally as an educator, leader, mother, and wife. It was a second graduate degree for both of us (my first in education and his in social work), and we did not want to relocate. We found a master of arts in urban mission program at Westminster Theological Seminary that allowed us to remain in the city while attending intensives at its Pennsylvania campus. After three years of part-time study—alongside doing ministry and raising our family—we graduated with renewed vision and a deepened calling to stay in the city.

In my last year of seminary, I joined the staff of City Seminary of New York, a grassroots, intercultural, theological learning community with a vision of urban theological education grounded in our particular context. I went on to pursue a doctorate in adult learning and leadership at Teachers College, Columbia University. Thirteen years from my first seminary class, I am now the dean of City Seminary. This is not only the fruit of my own labor, but the experiences of faculty, students, and graduates, who are also embedded in faithful ministry in and for the city.

* * *

While this brief biographical sketch frames a nontraditional narrative of theological education, the route I traveled into theological education is increasingly less uncommon in light of the greater fluidity of students in theological institutions across North America. While traditional institutions are trying to make sense of how to adapt, newer ones are finding ways to innovate and provide alternatives. Looking toward the future, it is clear that no single paradigm will dominate, but instead an ecology of possibilities that depend on each other in order to serve and form students in greater numbers and varieties will continue to grow. In light of transnational networks, this ecology will necessarily stretch beyond North America. In particular, we have much to learn from the growing Church in the global South as it strengthens its own institutional capacities and formulations of contextual theological education.

In order to envision a fair and just vision of theological education for generations to come, we must be informed by and open to the reality of change. The United States will be a majority-minority country by 2040. This means intentionally drawing on the diverse resources that already exist within North American theological education as well as beyond to meet these adaptive challenges. Those in formal leadership need to build bridges and share decision-making with others on the margins. This leads me to a second tale that broadens the scope of who is coming to theological education.

II. Family, Faith, and the City

One thing that people may not immediately associate with theological education is family. Yet while it may seem like an odd place from which to start, this is how theological education is most powerfully emerging in our context: couples, siblings, adult children and retired parents, extended family, church members, and colleagues have all come through our non-degree certificate program in urban ministry, seeking to be on the “same page” with regard to faith, ministry, and life. They have deepened and expanded our community of ministry learning and practice across generations, cultures, and traditions. Family is at the heart of our community; it is the relational strength of City Seminary of New York.

Our students come from diverse ecclesial backgrounds, range in affiliation from Pentecostal to Presbyterian, live throughout the boroughs of New York City, and have roots in countries around the world. They are church leaders, missionaries, multivocational pastors, youth workers, and faithful Christians in a variety of occupations. They desire to participate in a larger community of ministry and leadership, to gain tools for effective and fruitful practice, and to have a reflective space to explore vocation and calling. Families—enriched by their experiences in the program and mutuality of our community life—influence leadership and church life in diverse communities throughout the city.

One glimpse of the vocational diversity of our students is found in Miriam, our director of operations. Miriam is a minister at the Damascus Church of Hunts Point in the Bronx, part of an international network of more than 200 Latino churches. She serves as an officer at the council level, and she is married to Peter, an assistant pastor at Damascus (and also a full-time social worker at a Bronx hospital). Her daughter, brother-in-law, sister-in-law, and mother-in-law have all been a part of the Ministry Fellows Program.

Another example of this diversity is found in Ann and Janet, sisters and food entrepreneurs who were part of Ministry Fellows Program, six years apart. They live in Queens in a home with three generations, including their parents, and Ann and her husband’s daughter. “We Rub You” is their family business, sharing variations of a Korean-barbecue sauce made from a family recipe. They also partner with a local ministry by supporting survivors of human trafficking.

* * *

In this context, the two opposing models of Athens and Berlin are out of place. The scope of our work is neither individual character formation nor professionalization of ministry and critical research, but rather building a community from a complex mix of ministries grounded in the diverse traditions and expressions of the Church, and living out practices of ministry in the city over time. Students come during different seasons in their lives and for a wide range of reasons. This is how we together embody Christ in the city.

Andrew Walls offers an Ephesian metaphor that expresses our work powerfully:

The Ephesian metaphors of the temple and of the body show each of the culture-specific segments as necessary to the body but as incomplete in itself. Only in Christ does completion, fullness, dwell…None of us can reach Christ’s completeness on our own. We need each other’s vision to correct, enlarge, and focus our own; only together are we complete in Christ.1

At City Seminary, we experience an “Ephesian moment” in our own day. Wrestling with Scripture together and engaging in dialogue over the past and the present, formation, information, and transformation equip us to point others to Jesus as a community. Visiting each other’s churches, praying together, and sharing meals is part of what we do on a regular basis. And in the process, we become friends. Using the experience of a global city as our point of teaching and learning, we are able to expand beyond our North American context and cross transnational boundaries.

III. Women, Shared Wisdom, and Leadership

Inspired by my experiences at City Seminary, I wanted to better understand the journeys of racial-ethnic minority women leaders in theological education from Africa, Asia, North America, and the West Indies. In the four years of my dissertation research, I had the privilege of getting to know thirteen extraordinary women from these various locations who were or had been faculty and/or administrators in Christian theological institutions. Through a questionnaire, multiple interviews in the participants’ local context that formed the basis of written portraits, and a collaborative inquiry with a subset of participants, I had the opportunity to hear and experience the changing transcontinental dynamics in theological education. In an effort to make sense of each woman’s story, I interpreted them through the lenses of intersectionality, wisdom, and transformative learning theory.

In this work, I discovered a continuum of expressions in the ways each woman developed, practiced, and expressed leadership in the classroom, in the home, in administration, and elsewhere. Impacted by formative influences such as family, culture, and education, each had a deep sense of vocation and calling as she pressed on along a path that for some was unclear, and for others was aggressively blocked at times. As “tempered radicals,” they rocked the boat towards change from within the system, and met the pain of challenges with “resilient resistance.” They drew from a critical spirituality that provided each of them the sustenance for creativity, innovation, and self-efficacy as they matured in knowing themselves and integrating the multiple voices and identities they held. They engaged in an array of strategies along their journeys—what I described as dancing into a spiral labyrinth, the multiple centers of theological education. The dance was a “pilgrimage”: slow for some, improvisational for others, in partnership for some, and iterative for all.

* * *

These women’s experiences and stories led me to propose recommendations for revisiting curriculum, pedagogy, and administrative policies that are inextricably linked with the telos of theological education itself. If the purpose and meaning of theological education is to shape, equip, and transform God’s people—and in particular, women called to leadership, to become who they were meant to be, made in God’s image and as God’s beloved—then it is for God’s glory, for their blessing, and for the blessing of others. How then might theological education be crafted in ways sensitive to the perspectives, challenges, resources and strategies of racial-ethnic minority women as well as others who might not fit within the confines in which traditional theological education, here or abroad, has been formed? The “spiral labyrinth” metaphor points us towards this ecology of paradigms, located in multiple geographies, incorporating different paths and modalities, inviting a journey into one space and then towards another.

A Season of Hope, A Call to Solidarity

Theological education begins with grounding the present and shaping the future in knowledge of the past. It begins with the people of God coming to know who they are, whose they are, and where they are from, and then moving on to understand, practice, and embody faithful Christian living in the image of God while drawing others into this reality. It begins with embracing a vision of the unity and the diversity of the Church and acknowledging that there may be an entire ecosystem of theological education paradigms that we have not yet begun to imagine. In the context of changing times and politics, this work becomes more and more important to serve those who seek relevant and responsive education for the practice of ministry. The end, or telos, of this work is the flourishing of God’s people and God’s world, the reconciliation of brokenness, and glimpses of grace and wholeness in families, churches, and communities across the world.

As we look ahead to possibilities for the new forms theological education might take, are we willing to invite “others” both to the conversation and the planning table? The Church and the field of theological education are not complete unless we come into dialogue together to better understand how we can work in solidarity towards fair and just practices for the future. We have an opportunity to discover a rich, nuanced understanding of theological preparation and equipping that comes from mutuality of listening and seeing who the Church is, and who it is becoming. It is a season for hope, of possibilities for building new bridges between women and men, clergy and lay, across cultures, traditions, and geographies. It is time to take up the adaptive challenges of an increasingly complex and urban world, and weave together a tapestry of theological education that forms, informs, and transforms the people of God into faithful embodiments of the Gospel’s peace, grace, and joy.

Notes

1 Andrew F Walls, 2002. The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History (Maryknoll: NY), 79.

Maria Liu Wong is the dean of City Seminary of New York and a research scholar with the LearnLong Institute of Education and Learning Research. She has worked as an educator at the primary through tertiary levels for almost 20 years, teaching in New York City, China, and Ethiopia. She holds graduate degrees from Westminster Theological Seminary and Teachers College, Columbia University. Her research focuses on action research, adult learning, women and leadership, mentoring, diversity, urban theological education, youth ministry, learning cities, and the arts. Recent and upcoming publications include an article on world Christianity in New York City, chapters on collaborative mentoring, ministry in the city, spirituality, arts, and learning cities, and the forthcoming books, Stay in the City: How Christian Faith is Flourishing in an Urban World; Sense the City: A Handbook for Practicing Christian Faith in an Urban World; and Quality of Life and Adult Learning.

Maria Liu Wong is the dean of City Seminary of New York and a research scholar with the LearnLong Institute of Education and Learning Research. She has worked as an educator at the primary through tertiary levels for almost 20 years, teaching in New York City, China, and Ethiopia. She holds graduate degrees from Westminster Theological Seminary and Teachers College, Columbia University. Her research focuses on action research, adult learning, women and leadership, mentoring, diversity, urban theological education, youth ministry, learning cities, and the arts. Recent and upcoming publications include an article on world Christianity in New York City, chapters on collaborative mentoring, ministry in the city, spirituality, arts, and learning cities, and the forthcoming books, Stay in the City: How Christian Faith is Flourishing in an Urban World; Sense the City: A Handbook for Practicing Christian Faith in an Urban World; and Quality of Life and Adult Learning.

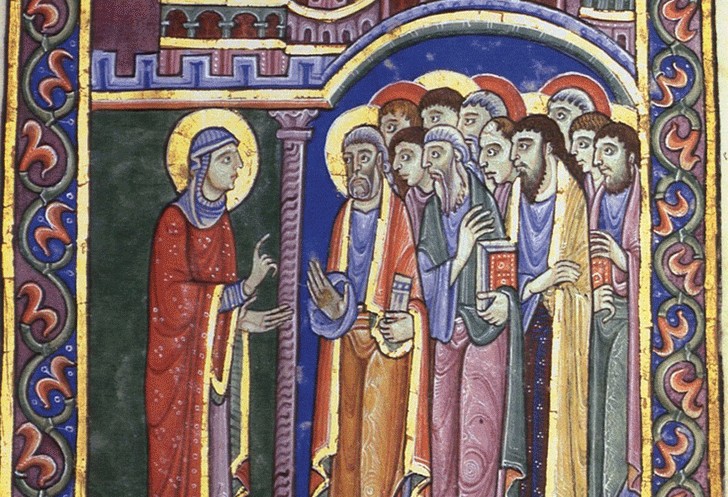

Header image: Mary Magdalene announcing the Resurrection to the Apostles, St. Albans Psalter, 12th century