American Secularism and Its Believers with Charles McCrary

Kristian Petersen:

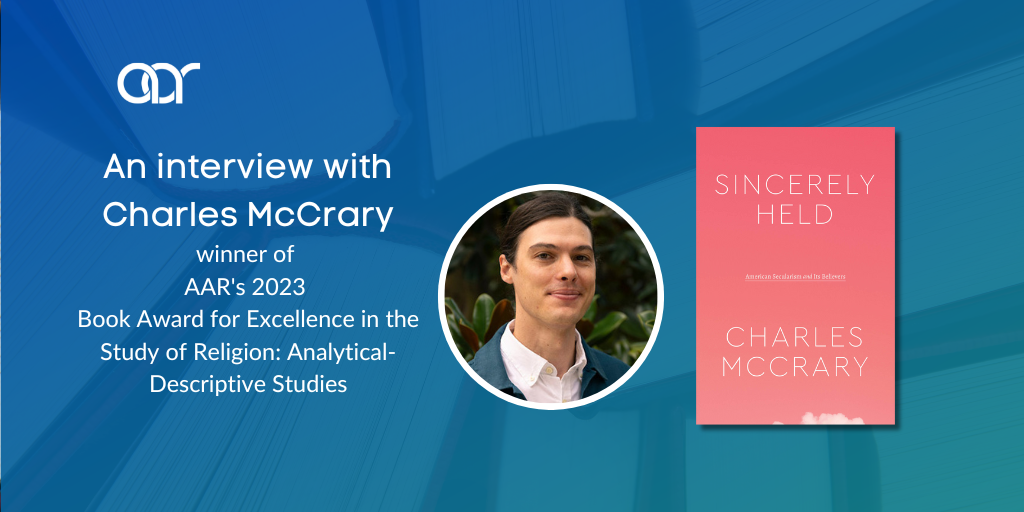

Welcome to Religious Studies News. I'm your host, Kristian Petersen, and today I'm here with Charles McCrary, assistant professor of religious studies at Eckerd College and winner of the 2023 Book Award in Analytical-Descriptive Studies from the American Academy of Religion. He's here to speak to us about his book, Sincerely Held: American Secularism and Its Believers, published with University of Chicago Press.

Congratulations and thanks for joining me, Charlie. How are you doing?

Charles McCrary:

Thank you, and I'm doing great. Thank you for having me on. I've been listening to you, Kristian, for well over a decade, interview authors about books, and many, many times I walked my dogs and listened to interviews and thought someday maybe Kristian will interview me about my book. And here we are. It's actually a little surreal and weird.

Kristian Petersen:

Here we are, my friend, and the pleasure is all mine. I'm grateful to have the opportunity not only to speak to you, but to read your book. It really is a great book and very interestingly put together, and I think a lot of people will find something in this book in our field.

To start us off, the book sits squarely between religious studies and then secularism studies, which I'm not as familiar with, but I have a distant picture of it in the horizon. Where would you position your book within scholarship on secularism and then, what were some of the conceptual interventions you were hoping to make with your book?

Charles McCrary:

That's a great question. It might be helpful for me to say how the book began a little bit, which it is based on my dissertation, but it has almost no dissertation content actually in it, but the basic idea was the same, which was that I was planning to write about broads and investigation and confidence men and the religious enactments that happened in 19th century United States because of uncertainty about the economy and society not knowing who people are. And so how do you know whom to trust? And so what religious ideas arise in that context? How do you know what's true and whom to trust?

At the same time, so this is like 10 years ago now, I was co-teaching a religion and law class with Mike Graziano at Florida State, and the Hobby Lobby decision had just happened where, not to get into all the details of that case, but it was a case about whether a for-profit corporation had to provide certain forms of contraceptives to its employees. It was a religious freedom case. It was controversial for a lot of reasons. And one of them was that this concept of sincerely held religious belief kept coming up as something to be protected and something that even a corporation might have. And so I started to put together this sincerity and law question with these questions about insincerity and fraud and investigation. So that's the genesis of the book.

Where I found my scholarly interventions, to answer the question more directly, is I was reading a lot of secularism studies or what might get called critical secularism studies in grad school, which can mean a lot of things, but for me, I'm really drawing from the work of two camps. One: American cultural studies, especially 19th century lit, people like John Modern, Emily Ogden, Tracy Fessenden, who look at -- like, in Fessenden's work, she investigated the ways that what we come to think of as the generic category of religion owe quite a lot to specifically Protestant forms. So this goes by the name Protestant secularism. I was thinking about that a lot, especially in terms of religious studies. We all study this thing called religion, and yet many of our definitions of what religion as the generic category are come from very particular and specifically Protestant sources. So how does that actually play out in literature and in culture? On the other hand, and relatedly, there's a lot of work in the anthropology of secularism by people like Saba Mahmood and Talal Asad. That work coming from post-colonial studies is about the governance of religion.

And so what I wanted to do is put those two things together, put those two - and a lot of people are putting them together, they're not so distinct bodies of scholarship. They're related to each other. But the question that I really wanted to ask is, okay, so these conceptions of what real religion is, they arise from somewhere culturally. They're Protestant tinged or inflected. For example, sincerely held religious belief, who cares about sincerity? Who cares about belief? It feels like a very Protestant conception of religion. Not just Protestants, but it's very individual. It's an individual believing, holding some belief inside, expressing it in public, so on. So it seems like a very Protestant thing.

So where does that come from? We can trace it in culture, literature and so on, but you can also say, how is that influencing policy? How is that being governed? How is that being shaped by the state? For example, through religious freedom law. So I think where my intervention is to ask those questions about secular governance, about the forms of religion that are policed, rewarded, guaranteed freedom, denied freedom, and then how does that actually work in the context of US free exercise law, is the most narrow version of the question.

Kristian Petersen:

Yeah, yeah. You've done a great job in both painting a portrait for those of us outside of this critical secularism studies in the book and then walking us through these episodes. But the book, as you've already mentioned, pivots both forward and backward around this idea of sincerely held religious belief, which came out of a Supreme Court case, Ballard versus United States. Can you maybe help us... Start there. Can you tell us a little bit about this case and its outcomes and then how this idea comes to crystallize some of the orienting terminology for thinking about religion and secularism in the United States?

Charles McCrary:

Sure. I'll try to keep this answer relatively short and then I can expand on it because this is really -

Kristian Petersen:

What you're doing in the book.

Charles McCrary:

Yeah [laughs]. Let me summarize most of the book. So starting with the Ballard case though, I open with this in the introduction. I don't spend that much time on it. In an earlier version of the book, I thought I would write a whole chapter and then ended up not doing that. But it's important to start there because this is a case, a Supreme Court case in the US, in 1944, where this group, the "I AM" Activity as they call themselves, or the "I AM" Movement, which was led by a man named Guy Ballard, also his wife Edna and his son Donald, and they were drawing from theosophy and metaphysical traditions, doing some channeling of spirits, divine healings, that sort of thing. So there's lots of these types of groups. They're also linked with some far-right movements. So they're active in California in the 1930s, but really spreading nationwide and then become quite popular for a while.

One claim that they make is that Guy Ballard was immortal. They also have stories of divine healing, of shaking hands with Jesus and other things that seem hard to believe. Guy Ballard's immortality seems especially hard to believe because he died in 1939. So they continue to promote the Activity to gain followers, to solicit donations, not fees, but donations they say. And eventually, Edna and Donald are arrested for sending fraudulent materials through the mail. They claim these materials are not fraudulent, they are true religious beliefs. Lower courts find they're not true, actually. And then other courts start to think, is it really the job of the secular state to determine whether religious beliefs are true?

And that's eventually where the Supreme Court comes down on this, is to say, "It's not our job. We cannot evaluate the truth or falsity of religious beliefs. What we can do is evaluate whether people sincerely believe them." And so that becomes the sincerity test in American law because it is secular, because it is not supposed to make theological pronouncements. You can't say that somebody's religious belief is false or true. What you can do is say, does this individual sincerely believe this? Is that really what you believe? And if so, it can be protected.

Kristian Petersen:

So from this conceptual framework of this idea of sincerely held beliefs, you look at the relationship between religious freedom, sincerity, secularism in the United States through this episodic genealogy. You cover all sorts of great topics that we won't get to cover. So just for the listener's sake, it's largely chronological your account, although it's not a comprehensive account. You look at things like Herman Melville's novel The Confidence Man, American morality police, spiritualist women accused of being fortune-tellers, and these other frauds that you mentioned earlier. Later on, you look at conscientious objectors to war, you look at atheist court claimants. There's sections on Black revolutionaries and civil rights activists, and you bring us all the way up into the present day thinking about litigants in this Christian legal movement within the same vein as the Hobby Lobby case you had mentioned earlier. So you really cover a great deal of terrain.

I won't ask you about all of these, but looking at this longer history, what are some of the things that these moments tell us about, the legal history of sincerity and religious freedom jurisprudence in the United States? What are some of the main takeaways that you found?

Charles McCrary:

What I was most surprised by, and like you said, there are a lot of examples in the book, and I could've included many more. It was one of the hardest parts about writing. It was deciding which episodes were really worth focusing on which ones needed a whole chapter, or in the case of the conscientious objectors, really like two and a half chapters. So that's what surprised me the most is how central conscientious objection to war is to this whole history. It's surprising in part because from a legal perspective, those are not First Amendment cases. Those are not strictly speaking religious freedom cases. So the First Amendment to the US Constitution has a free exercise clause. "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion" - that's the establishment clause - "or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." Right, the government can't pass laws that restrict your free exercise.

So most religious freedom cases, as we think about them when they make their way to the Supreme Court or wherever, have something to do with the free exercise clause. These conscientious objection cases actually don't, at least not strictly speaking, because they are interpretations of a statute a law, which is the Draft Act. So I trace this whole history of, I really got into the minutiae of this, the 1940 Draft Act, the 1948 Draft Act that updated that, the congressional fights over language. But this really came to matter quite a lot because the cases that happened as a result of these fights lent a lot of their language to what became First Amendment law.

So for example, when you fill out, if you would like to fill one out, a vaccine exemption form, you have a religious belief that says you should not get the vaccine, whatever vaccine it might be. So you fill out some form and give it to the HR professional at your workplace or however it works. A lot of the language on those forms are taken directly from conscientious objection cases and from the Draft Act in the 1950s and '60s. So I spend a lot of time talking about those cases and how they actually work in the original... So I can go into a lot of detail here, but I'll keep it relatively brief.

Kristian Petersen:

Read the book, right?

Charles McCrary:

Yes, I would start with chapter four. If this is what really interests you. This is chapter four. Before 1940, if you wanted to become a conscientious objector to war, you had to belong to a historic peace church, so Quakers, Mennonites, somebody like that. In 1940, the Draft Act changed - Congress changed it - to say anyone who objects to war by reason of religious training and belief. That is very broad, that is very vague, there were lots of fights about this, especially as the US got into World War II and many people had reasons not to want to be drafted. So they would fill out paperwork explaining their individual belief, sometimes extensive paperwork. They would appear before these draft boards. They would make their case and say, "Here's why I believe what I believe." They would solicit letters from friends or clergy or parents.

And there was this vast apparatus in the Selective Service Agency to wade through all of these. This resulted in a series of court cases and then a revision to the Draft Act to try to clarify it, but it really just made it more confusing, I think, and then more and more cases, and eventually we get to 1965 with US v Seeger, or this guy Dan Seeger, who did not affirm a belief in God and was not a member of any church, although he was involved in some Quaker meetings and eventually a lot more involved. He said that he did not believe in God, but he had this serious moral conviction that war was wrong. And the Supreme Court found that that basically counts, that his sincere belief was religious, not because it was a belief in God, but because of how he held it, because it was so - and they cite Paul Tillich, which AAR members will be familiar with, this definition of religion as ultimate concern, a man's individual ultimate concern. The Supreme Court uses that and says, "Okay, this is his ultimate concern. This is the thing that is most important in his soul or in his heart that directs his actions. And that is basically what religion is. And so that counts."

After that, that language because it's so flexible and so useful, gets taken up in a lot of religious freedom cases even through today. But because it's so expansive, the court then must find its limits and say, "Okay, not everything can count. Not every deeply held belief that you just think is important is the same as a religious belief," but who decides that? What are the limits to it? And so that's where so many religious freedom controversies over the last few decades have really stemmed from that question.

Kristian Petersen:

There's lots of directions we could go with the book, but one I wanted to ask you about was in several of the chapters, you're dealing with questions around race and secularism, which if I'm familiar enough with it, it's a newish area of study. I think Vincent Lloyd, Christopher Cameron, maybe a couple others have started to work on race and secularism. In your study, because this comes up in the later half of the book, what role does race play in thinking about sincerity and religion?

Charles McCrary:

Race is really central to my discussion here, even as it's sometimes not explicitly, it's often not explicitly discussed by the courts, but I think about race in terms of racialization. I'm really influenced here by Barbara and Karen Fields, their discussion of Racecraft, that vein of scholarship on race making. And this question, which I think is really central to a lot of what's going on in religious studies now, which is what is the relationship between race making and religion making? A lot of people say, race and religion are co-constituted or co-constructed, but what does that actually mean? How does that co-construction happen?

And so when I think about racialization, I think about the ways that certain populations are defined as different or separate and thus colonized or oppressed or subjugated, treated differently based on some supposedly immutable characteristics or something like that. It's a very broad definition. Much like secularism though, in this critical secularism studies vein, it's not really the case that these categories, these differences are real and people notice them and then they enforce those differences, but rather that those differences are the product of the acts of enforcement. So if you colonize a population and point out or construct certain differences, then those differences will start to appear natural. And so it's an act of governance.

So in that way, the policing of the boundaries of religion, what counts as a real religion, what's rewarded with religious freedom and what is not are oftentimes tied up with acts of racial governance. So an example of this is, well, one, with Dan Seeger. I mean, I argue... I don't argue so bluntly that he won his case because he is white. It's not just that. But he was more recognizable as a normatively religious subject because he looked Protestant even though he wasn't Protestant, but he was a white middle-class individual who expressed his beliefs in a certain way. His religion was about deeply held belief rather than ritual. And so we can think about the long history of religious studies as privileging belief and so on over ritual, even tracing this back to Protestant Catholic, well, warfare and divides over this. Think about the work of Robert Orsi on this and lots of other people too, about these religions that are about individual thinking, belief, and religions that are about the fetish or the ritual or presence and substance rather than absence and so on.

And as the work of scholars like Sylvester Johnson show, these are already racialized discussions. The whole idea of the fetish of African religions, African practices being not really religious, not really Christian because they misapprehend what matter is supposed to do. There's something fundamentally different about them, and thus because of their improper religion, they are not fit for self-governance. They're fit for colonization, even in some cases killing or genocide. We see this with Native Americans as well.

So this is the dark underside, or not even the underside sometimes, of secular governance, which includes religious freedom, which seems like a great thing, we like religious freedom, and yet it's always based on a certain understanding of what counts as religion. And that's always an act of governance. That's always an act of separating the colonized from the colonizer. And it's not just indebted to those inheritances in some vague way, but it's really still an animating structuring force. So that, I think, is the relationship between race and secularism as I see it and as I try to trace out in the book sometimes in unexpected places, but I really think it's deeply written into the structure of how secular governance and racial governance are working as, if not the exact same thing, then certainly hand in glove.

Kristian Petersen:

The end of your book, you do a quick reflection on our present moment, this post-truth era that we live in. And I'm wondering what your thoughts are on how do you best see us as religious study scholars putting our disciplinary skills to use, whether that's through the study of law and religion or something like critical secularism studies or something else. How can we best come to the fore in our new cultural moment here from your perspective?

Charles McCrary:

This is the question that everybody asks me, and I still don't have a very good answer for it. I visit people's classes sometimes, a few of my colleagues have assigned the book and I go to talk to the students and they all want to ask something about this, and I wish I had something better to say, but hopefully this is good enough. I actually argue strangely, to me, that sincerity might be resuscitated as a worthwhile public ethic, even as a break-down that it rests on certain fictions of the individual subject and so on. But I think there's some positive public good that could be done by the idea that we should be true to others rather than authentic to ourselves, be who you truly are, but something more communal, recognizing that we are shaped by others and always in connection with them and thus trying to be legible to other people. I think there's something in that.

The question about post-truth, and I don't quite know what to make of that still other than to say, I've always thought it is strange that the rise of sincerely held religious belief takes place at the same time as the supposed rise of a post-truth era. So what is the relationship between not caring about truth and caring a lot about sincerity? Those two things seem to be at odds. So how do we resolve this? And my argument there is that they actually work together by de-emphasizing the content of what people say, right? If you care about sincerity, it doesn't really matter if what somebody is saying is true, it just matters whether they really believe it.

So I think that actually works with this supposedly post-truth moment. And one of the problems in our public discourse is not just an inability, but sometimes an unwillingness or at least a hesitation to really investigate the content of what people say. There's so much attention to people's lived experience, a lot of deference to people who will speak from certain lived experiences, and I think that is good. In some ways, we want authentic politicians. That's very much in the news as we record this. So much support for the Harris-Walz ticket is because they seem authentic. They're real people as opposed to the apparently not real people on the other side, the weird people who don't seem relatable. All of that's fine, and I think sincerity can be a good public ethic, but I do worry that an emphasis on sincerity contributes to the rise of post-truth by de-emphasizing the content of what people say and instead just paying attention to whether they are authentic, whether they really believe what they say rather than if it's actually true or makes any sense.

And I think a little more focus on whether things are actually true and make sense would probably be a good thing. But this is a big problem for religious studies because many of us, including myself, are not really equipped to evaluate truth claims. A big part of what we do is to kind bracket that off, which is the same secularist move that the sincerity test makes. How do we resolve that? I mean, I don't really know. I have some thoughts, but honestly, they're not that good. So I'm hoping other people take that up. That's the big problem, I think. Where do we go in this post-secular movement? Is it a return to political theology? That's what some people would argue. I think that might be right, but I also don't quite have the tools to do it. But I really think that is a big problem or issue or opportunity facing religious studies as a whole field. What do we do when our bracketing of truth claims has started to fail us and it started to replicate the same secular structures that we interrogate? But I'm not quite sure of the way out of it.

Kristian Petersen:

Well, thank you, Charlie, for writing this great book. It's certainly food for thought for those that will pick it up and dive into some of these chapters. I think you're right, that hopefully people will continue this conversation and perhaps help us further understand what these issues are and how we might move forward with them. But congratulations again on the award and thanks for making time to talk about the book.

Charles McCrary:

Thank you. This was great.