Art as Embodied Experience with Kathryn R. Barush

Kathryn R. Barush joins Kristian Petersen to discuss her award-winning book Imaging Pilgrimage: Art as Embodied Experience (Bloomsbury Publishing). Expanding the concepts of “pilgrimage” and art as lived experience, Barush's book extends the idea of communities as culture.

Kristian Petersen:

Welcome to Religious Studies News. I'm your host, Kristian Petersen, and today I'm here with Kathryn R. Barush. She is the Thomas E. Bertelsen Jr. Professor of Art History and Religion at Graduate Theological Union, and the 2022 winner of AAR's Religion and the Arts Book Award. She's here to speak to us about her book, Imaging Pilgrimage: Art as Embodied Experience, published with Bloomsbury. Congratulations and thanks for joining me.

Kathryn R. Barush:

Thank you. My pleasure.

Kristian Petersen:

So this is a really cool project. You're bringing lots of different threads together around this kind of conception of pilgrimage beyond the ways we often typically think about it, as simply a religious practice. So can you begin by just telling us a little bit about how this project started to emerge for you and what were some of the kind of broader conceptual interventions you were hoping to make with your book?

Kathryn R. Barush:

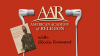

Yeah, thank you. It actually came out of an earlier project from 2003. I had a Thomas J. Watson fellowship, and for that I did a comparative study of Christian and Buddhist illumination as a sort of virtual pilgrimage for the people creating these artworks. So for that project, it was such a great opportunity. I hadn't traveled much prior to this and I was able to go to Tibet. I was in Greece, I was all over the UK, and I was able to actually work with people who were doing Thangka painting and illumination. And as I kind of started to talk to people in these monastic communities, they explained to me that the process of making these sacred artworks, mandalas and let's say Celtic artwork and illuminated manuscripts, especially for people that were in a monastic community, it was a way for them to travel virtually. You can kind of almost imagine something like a knot work in, let's say the Book of Kells, and - I am an art historian, so it's hard for me to do an audio interview because I'd love to show you a picture - but if you Google the Book of Kells and you look at a knot work or even an initial from the Book of Kells, there are very intricate kind of knot works that go where the line of the letter goes up and down and around and over and under.

And if you imagine being in a place where people are doing this kind of illumination work, and you can imagine having a little brush and kind of following those intricate matrices going up and down and over, you can kind of get the sense of this pilgrimage even using a brush or looking at that material and having a virtual experience through your imagination. So I decided to take this idea of this virtual pilgrimage through making and viewing artwork and apply it to contemporary art production. That is how the book Imaging Pilgrimage was born.

(Fig. 1 - Book of Kells via World History Encyclopedia)

Kristian Petersen:

That's cool. Your struggle to talk about the artistic representation was a little bit of the experience as a reader as well. I wanted to be in some of these places or hear some of the things that you were talking about in the book, so I can empathize with how we're tackling this topic.

You've already alluded to this a little bit, this kind of general approach of focusing on the material culture of pilgrimage in its various forms. This is one of the main theoretical threads. So I guess, in a more pointed way, what would you say we can learn from the artifacts, the relics, the souvenirs of pilgrimage, in addition to talking about pilgrimage as a ritual act at some place-based site?

Kathryn R. Barush:

Thank you. That's a great question. And one of the things that I tried to accomplish in the book was to develop a notion that I call communitas through culture. Communitas is a term that was kind of brought into the anthropological sphere by Victor and Edith Turner in the 70's. And it's been marshaled in anthropology to think about dynamics within a pilgrim group. So when a group of pilgrims arrives at a shrine, it's kind of been used to describe the collective feeling of wonder that the pilgrims might experience. And, in addition to research and working on books, one of the other things that I actually do is lead groups of pilgrims along routes like the Camino Camino de Santiago in Spain. And the more I interfaced with pilgrims and talked to my students, the more it occurred to me that when the pilgrim comes into contact with a holy object, like let's say the Black Madonna of Montserrat, they are not just there with the object. They're there in the presence of what the object represents in this case, the Virgin Mary. And they can also feel the presence of all the people that have come before and all the people that will come again in the future.

It's almost liturgical. It feels almost like when you're in a liturgy and the voices of the saints and angels are invoked in a Christian or Catholic liturgy. It really feels like a crowd of people and ancestors are with the pilgrim. So throughout the case studies in the book, this was something that emerged over and over again in various cultural and religious contexts. That was one of the main things that I tried to draw out. So not just the communitas as in the collective experience of the group of pilgrims, but a communitas, as in a communion across culture and time where presence was perceived.

Kristian Petersen:

Another key aspect of the project that I think a lot of people in the academy will appreciate is it's very pluralistic, and you do a lot of analysis around these kind of dialogical encounters across different cultures and traditions. And it sounds like from your biographical description earlier, a lot of this was based on these kind of opportunities you had. \

But what does this cross-cultural context of the project of gesture to you in the sense of material culture of pilgrimage? Why was it important for you to highlight this pluralistic aspect in your work?

Kathryn R. Barush:

Well, just, thank you. That's a great question, too. And just to go back to the fact that I did actually bring in a lot of personal narrative and story. It was something that was really important to me and I didn't really know how to describe that aspect of my methodological approach until I had the opportunity to have my book discussed by the anthropologist Simon Coleman, who's the Chancellor Jackman Professor in the Arts at University of Toronto. He did a great kind of response to my book where he called my approach an ethno-art history. And I just really loved that description. Sometimes it takes someone else to explain, to widen the aperture a little bit and to describe what you're doing as a scholar. And I really appreciated his way of describing this. So I did want to see how far I could push this idea of communitas through culture.

I sometimes call it in the book extra-temporal communitas. I also talk a lot about the transfer of spirit from place to place and how pilgrimages can be mapped through art or assemblage from one sacred place and then kind rebuilt or reconstructed in another space for communities to appreciate. And so through the different chapters, I traced this through various case studies. I wanted to see how many people I could focus on who invoked these sorts of ideas and themes in their artistic production. So as you're alluding to, there's a kind of diversity of folks starting with someone who created a Camino in his backyard in the Pacific Northwest to a repurposed prisoner transport bus where a site from Ecuador was reconstructed. There's cigar box shrines from Southern Africa. So anyway, I did try to see how these themes and ideas can translate into different cultural contexts.

Kristian Petersen:

Yeah, yeah. I'd love to dive into a couple of these examples just to give listeners a kind of taste of what you're up to in the project. But you mentioned this first one, the Backyard Camino. Can you tell us a little bit about how this local experience in the Pacific Northwest relates to the original in Spain? And then you also kind of do this multilayered approach where you then look at a documentary about this experience and how this might circulate the meaning of this experience.

Kathryn R. Barush:

Yes. I love this case study. This is what I open the book with because I think it's a really great example of what I'm trying to achieve. The story behind the Backyard Camino is that it was developed by a guy named Phil Volcker. He studied landscape architecture, but went on to move out to Vashon Island to start a cabinet-making business many years ago.

And he became very interested in the idea of walking the Camino de Santiago, which is about a 500-mile pilgrimage. You can start in different places, but many pilgrims today start in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in France and travel to the place where the remains of St. James the Apostle are interred in the Church of Santiago de Compostela. And Phil had gotten very interested in walking this pilgrimage. He had seen this film called The Way, which is directed by Emilio Estevez and is a kind of a Camino journey, and things kind of came together for Phil. It looked like he was going to be able to walk the Camino.

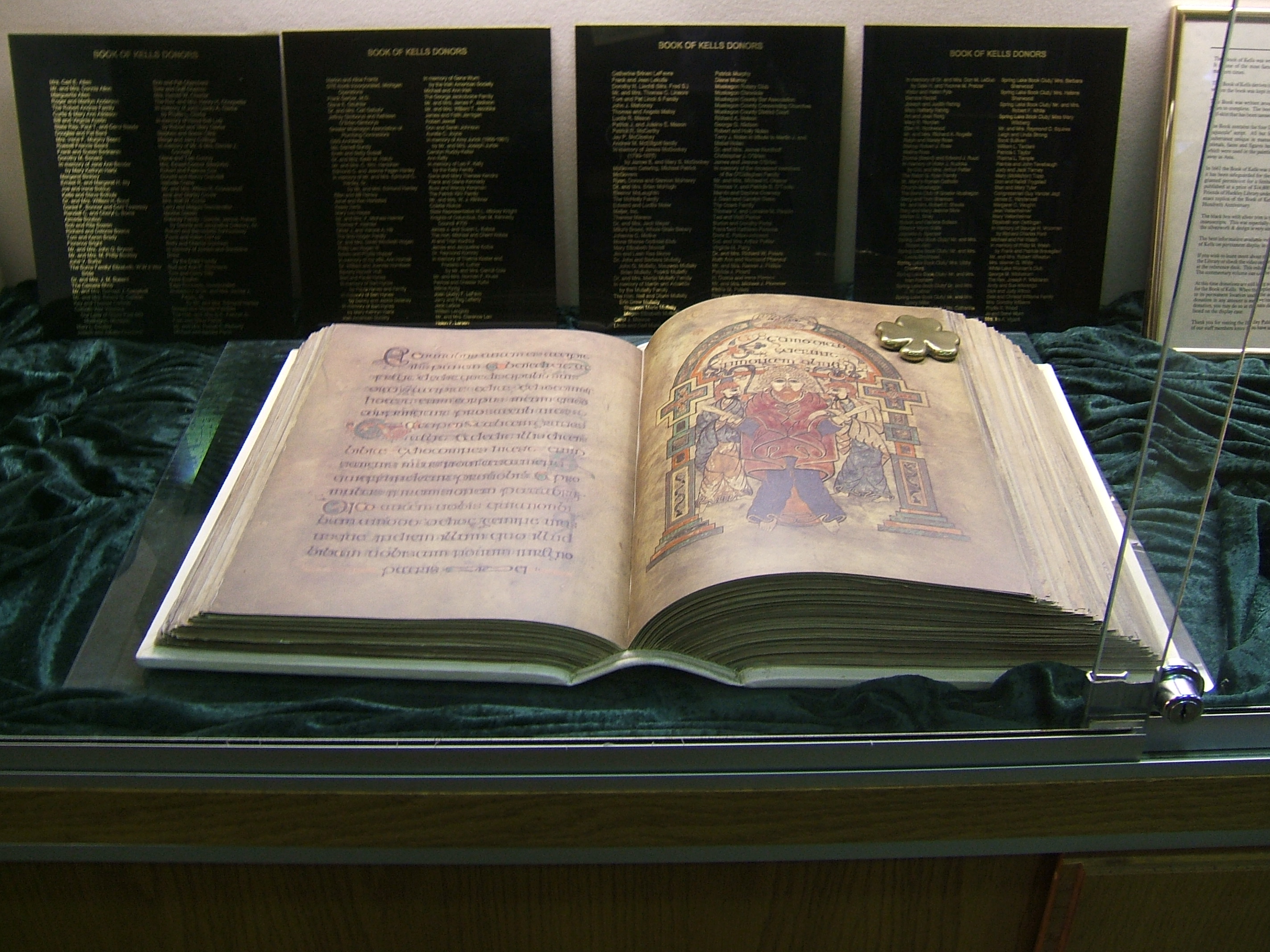

Unfortunately, he received a diagnosis of stage four cancer that had already metastasized. His recovery oncologist, Dr. David Zucker from the Swedish Cancer Institute in Seattle suggested that Phil just start walking. And Phil is lucky in that he has quite a big backyard. It's a big property where he has a small cornfield and there's a small river - if you get the book or if you have a chance to look at the book, there's actually a map of the backyard, earlier when we were talking about visual material, [the book] actually comes with a number of really beautiful, kind of well-produced color images in the center, and one of them is Phil's map.

(Fig. 2 - Phil's map via Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation)

In any event, he started to walk around this backyard of his, and he realized at one point that he was putting in a lot of miles. So he took out a map of the Camino de Santiago and kind of mapped how many miles he had walked in the backyard onto the map of the Camino, and he realized he had arrived at a specific town.

So from that point forward, he started to kind of record how many miles he was walking in the backyard and look at the map of the Camino. And then eventually he would arrive in a town like Burgos, and he and his wife Rebecca would have a tapas celebration with food and neighbors in the backyard, maybe even a regional wine, to toast his progress along the Camino. And he did it. He walked the entire Camino to Santiago in his backyard, and eventually he became quite well enough to have one month off of his chemo treatments. He went to Spain, walked the Camino in Spain, and then returned to his backyard and continued to walk the Camino many more times. So the point that I make in the book is that the Backyard Camino kind of takes on what Phil called "a life of its own."

People started to come to his backyard. It became a sort of pilgrimage in and of itself. He would say the rosary sometimes out loud, sometimes silently as he walked around the backyard. And he actually installed bird feeders at the places where you pray the "Our Father," so it also became a rosary walk. People came to be with Phil to walk in the backyard to reflect and to pray and to just be with nature and feel a closeness with God. People from all faiths and on kind of came to walk in Phil's backyard.

There's a documentary film - a short doc - called Phil's Camino. And I also make the point in the book that even watching the film becomes a sort of pilgrimage experience. So there's multiple layers here. There's the Camino pilgrimage, and you could also make the point that pilgrimage is a reflection of the human experience from birth to death and beyond, depending on which faith one comes from. So there's kind of the Big pilgrimage - the Augustinian where we're we're kind of progressing through, that's the Big pilgrimage. Then there's the next level of pilgrimage, which in this case is the Camino de Santiago. Then there's the mapped pilgrimage on Phil's backyard in Bashon Island, and then there's a film. So these are all different ways to experience pilgrimage, to experience sacred journey.

Kristian Petersen:

Yeah, I really like that example, too. You also earlier mentioned this art installation in this repurposed bus, which I think also is a great example that helps us think through this material culture. So can you tell us a little bit about this artist's project, how the blending of Catholicism and indigenous beliefs inform the art, and then how it helped you think about what it means for sacred objects to be decontextualized from their original space?

Kathryn R. Barush:

So the bus was something that I encountered actually right close to my home in Berkeley on San Pablo Avenue. It was parked, and there was a sandwich board that said, "Come on up, art on a bus."

And the way that it was set up is that you kind of walked up the stairs. It was an old school bus, and you walked in through the two back doors that opened up into a sacred space. It reminded me of the barrel vaulting in a medieval cathedral. And when the artist Gisela Insuaste had first encountered that bus, it was in a kind of darkened garage in San Leandro, California. It was part of a project that was set up by Jen Stager. She's a curator and also a professor of art history at Johns Hopkins. The idea was to kind of take this decommissioned prisoner transport bus that had subsequently actually been a Burning Man camp and turn it into a roving art space.

So Gisela was the first artist to be able to do an installation on this roving art bus. She was thinking about what she wanted to do, and she was taking photos of the bus in this garage in San Leandro, thinking about what kind of an installation she wanted to create when the flash of her camera illuminated these scratches on the windows of the bus.

(Fig. 3 - Altarcito via https://www.giselainsuaste.com/)

She immediately thought of all those people who had been incarcerated, who had done the graffiti on the windows of the bus, so she ended up taking those scratches and making them larger through gesture. She actually used colored tape to kind of create this matrix of tape over the roof of the bus to draw out those stories, those gestures of the people who had sat on that bus.

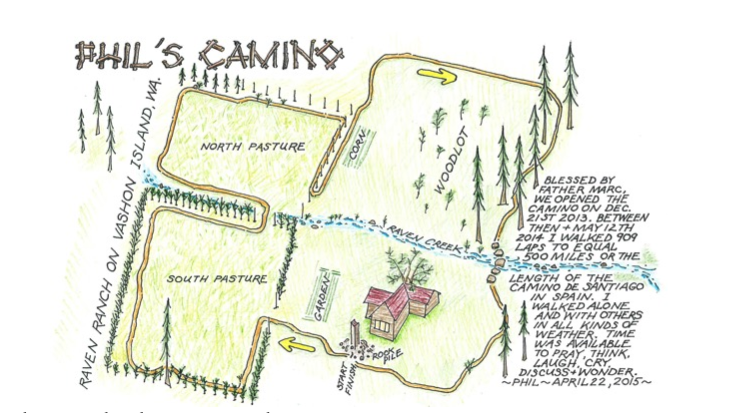

And then to kind of even further this experience of pilgrimage, she created a dashboard altarcito where she had a picture of her parents who had immigrated from Ecuador to New York City in the 70s to start a vacuum cleaner company called Desco Vacuum in Manhattan. And there were a bunch of other objects that she had collected from a sacred site in Ecuador, Our Lady of the Sacred Bass. So there was some water, there was some moss, and there were some wrappings made out of wool. And I'll just pause for a minute just to talk about the moss, because you had asked about her conjunction of her Catholic and Quechua heritage. The moss was a really important element for her because it was a place where there was a statue of el nenito - the baby Jesus, who's carried in processions in Ecuador - and the baby is sort of recumbent on a bed of moss.

And for her, it invoked that. But it also made her think of the Apus, who are the spirits of the Andes. And she says that when she rides her bike through Oakland, she's always thinking about the Apus who inhabit what is called "the more than human" in indigenous cosmology. And so the moss was kind of a very important element that combined these things. There was an artist that I interviewed, a fellow artist that I interviewed for the project, who called the moss a sort of repository of migrant experiences. And this was something that was kind of enshrined in this dashboard altarcito as part of this really beautiful transfer of this Ecuadorian pilgrimage onto this place.

Kristian Petersen:

Yeah, all the projects you explore in the book are really fascinating. There's several more that we won't have time to go into great depth, but I did want to ask you as a wrap-up, how you imagine others in the study of religion might benefit from your work, either in how you apply your methodologies or the types of things you analyze. What do you think that those beyond your subfield will engage this book?

Kathryn R. Barush:

So actually I have a funny story about this that I'll share. I'll just give one example of maybe an unexpected place where my critical framework has suddenly appeared. And this is in a book hot off the press by Naomi Seidman, who is at the University of Toronto. She was formerly my colleague at the Graduate Theological Union, and she has a book out called Translating the Jewish Freud: Psychoanalysis in Hebrew and Yiddish. And you might not think that this would be the obvious place to think about these ideas of pilgrimage and communitas through culture. However, she frames her book with this idea of what she calls "the Freud closet," and it's actually a physical closet in her home in Berkeley where she was collecting objects related to Freud. And I'm looking at the back of the book right now, and the blurb on the back of the book says, "What is it that propels the scholarly aim to show Freud in a Jewish light? Nomi Seidman explores attempts to 'touch' Freud and other famous Jews through Jewish languages seeking out his Hebrew name or evidence that he knew some Yiddish."

And so she uses the idea of communitas through culture and actually invokes a moment in my book where I'm talking about a reconstructed lord's shrine to think through what these objects mean and how they can invoke the presence of Freud, and you can get to know him through the tactile experience of these objects associated with Freud. So I thought that that was a very interesting kind of place where this has emerged. I also have a student right now that's using the idea to apply to art images of the Virgin Mary in a Taiwanese context, looking at a number of case studies in various groups of people who live in Taiwan. So it is something that seems to be able to transfer into various contexts, which is great, and I hope that people continue to use this idea.

Kristian Petersen:

Yeah, yeah, I think certainly. I mean, you illustrated in your book already, but I do hope others will pick up the book and follow your leads. So thank you for your time, and congrats again on the book award.

Kathryn R. Barush:

Thank you so much for the opportunity.