The Role of Western Universities in the Education of Scholars of Islam

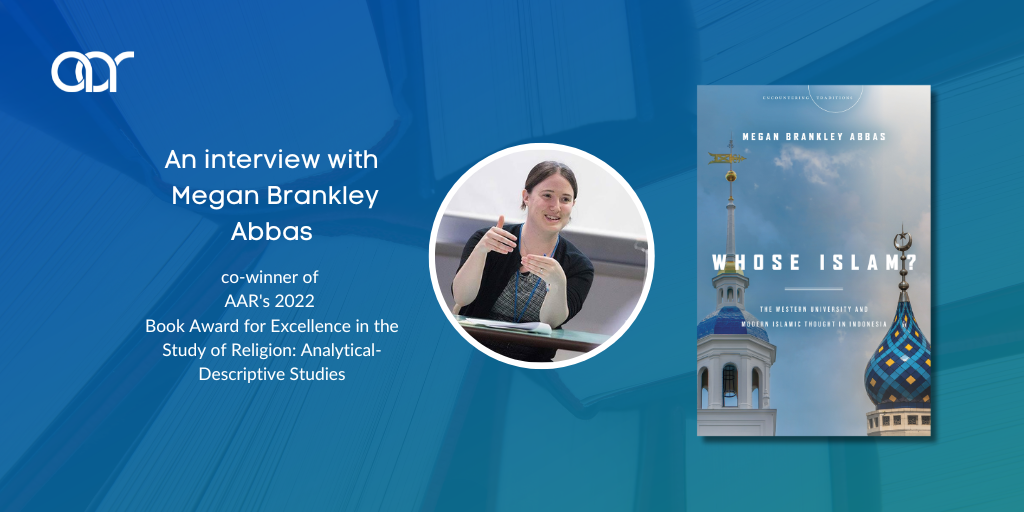

Megan Brankley Abbas joins Kristian Petersen to discuss her award-winning book Whose Islam?: The Western University and Modern Islamic Thought in Indonesia (Stanford University Press). Abbas's book "thoughtfully discusses the question of authority in Islamic studies, both religious and academic, infusing the insider-outsider debate with new empirical evidence and profound insights."

Kristian Petersen:

Welcome to Religious Studies News. I'm your host, Kristian Petersen, and today I'm here with Megan Brankley Abbas, associate professor of religion at Colgate University and co-winner of the 2022 AAR Book Award in Analytical-Descriptive Studies. She's here to speak to us about her book, Whose Islam?: The Western University and Modern Islamic Thought in Indonesia, published with Stanford University Press. Congrats on your award, Megan, and thanks for joining me.

Megan Brankley Abbas:

Yeah, thanks for having me.

Kristian Petersen:

Yeah, this is a really cool project and kind of unique in its approach. You're tackling the development of Islam in the context of Indonesian exchange with North American academic institutions. Can you talk about how this project started for you? Where did this kind of transnational exchange pop up on your radar and what made you say, this is the way I want to approach this?

Megan Brankley Abbas:

Yeah, so actually the project began as another project altogether. I was interested in the Indonesian Ministry of Religious Affairs, which is an Indonesian bureaucracy that manages mosque construction, religious education in schools, et cetera. And I started diving into the Indonesian religious ministry and started thinking about the background of the various leaders of it, and started to notice that a large number of the leadership - top ranking leadership in the ministry - had McGill graduate degrees, so master's degrees or PhDs in the 1970s and beyond. And that struck me as surprising and then reminded me of something I had noticed in an earlier seminar that I had taken in grad school that several of the most recent leaders of Muhammadiyah, which is the largest modernist Islamic organization in Indonesia with like 20 million plus members, also had Western PhDs. So that really kind of struck me as an interesting pattern that I hadn't really seen anyone delve into: why so many major Indonesian Islamic leaders had western academic degrees in Islamic studies. And therefore, I started to ask questions and do the research on what exactly the relationship is between Islamic theology or Islamic politics in Indonesia, and what we might call the academic study of religion in Western universities.

And where that line is between those and how that line might be collapsing in the Indonesian context.

Kristian Petersen:

And a kind of major thread across many of the thinkers, whether they're taking up this perspective or kind of critiquing it, is this kind of new development of an interpretive approach to Islam. You dub it fusionist, and you're kind of, maybe I won't spoil it and let you respond, but you're responding to this context of modern Islam, contemporary Islam often being either kind of traditionalist or modernist in its approach. And this seems to be kind of a different option. So can you talk a little bit about what you mean by this term? And then tell us a little bit about maybe how this small sliver of scholars gives us a new intervention into thinking about the diversity of Islamic thought?

Megan Brankley Abbas:

Yeah, sure. So two of the main concepts that I'm playing with in the book are what I call dualism and fusionism, as you mentioned. So it's some ways easier to kind of start with how I define dualism, because fusionism is a reaction to it. So dualism I define as a conceptualization of Islamic thinking as distinct. A distinct tradition from western academic traditions. So you can think about dualism as saying that there are certain texts, certain scholars, certain methodologies that belong to the Islamic tradition, so Quranic exegesis. And then there are certain traditions, certain scholars that belong to western academic traditions, whether that be psychology, history, et cetera. And that is - dualist thinkers would build institutions that represent that. So have a Islamic curriculum or western style curriculum and also associate with one of those traditions over the other. And they'll often kind of argue that that's how things should be, that the Islamic tradition should be located in a madrasa, should be a special type of curricular path, and that there should be western academic style schools that have a different kind of goal and a different set of instructors, instructors, curriculum, et cetera.

So fusionists are then, a reaction to that, and these are predominantly Indonesian Muslim thinkers who I'm looking at who really want to break down the wall between the western academic and the Indonesian Islamic traditions and really integrate the two. They make arguments that say, we can't really study the Quran without studying literary hermeneutics from western academic traditions, and we're going to apply those literary hermeneutics into Quranic studies and create something new and integrated out of that, or take western critical historical methods, put them into studies of the life of Muhammad and create something new out of that. So I'm really looking at people who are intent on destroying that boundary between the western academic and the Islamic tradition, both in their own thinking, but also institutionally. Building institutions, schools in particular, that are intent on kind of merging in a real kind of deep integrated way, the two traditions.

So when I think about what these figures have been doing in Indonesia, they produce some really exciting scholarship that looks a lot at how to integrate Islam into development economics, in particular in the 1970s and 80's, so that we can get development economics that have Islamic values built into them, and that Islamic interpretations that take the social reality around them, the kind of economic policies and system deeply into account. But I also think that to me, the other interesting thing that these Indonesian fusionists are doing is that they fundamentally challenge what a madrasa or an Islamic institution should look like, but also what a western academic university is doing. By kind of attacking that line between the two and merging them, they kind of create these questions about, well, what exactly is the purpose of an Islamic education versus a western academic one?

Kristian Petersen:

So you do this through these various biographical sketches in these various kind of waves of exchange back and forth in the early first wave. We have Indonesian academics coming to McGill University. Can you tell us a little bit about what this early exchange looked like? What were the political and religious results of this kind of cross-cultural exchange?

Megan Brankley Abbas:

Yeah, so as I mentioned earlier, I got really interested in what some people call in Indonesia, a McGill Mafia. So this group, at this point over 200 Indonesian Muslim leaders, bureaucrats, politicians who have masters and PhDs from the McGill Institute of Islamic Studies. So it's not even McGill as a whole, it's the McGill Institute of Islamic Studies in particular. And so I started diving into the history of the McGill Institute of Islamic Studies and thinking, well, why is this place of all place this kind of bastion or this kind of mecca, for lack of a better word, for Indonesian Muslim scholars? And to me, this is really about the way that Wilfred Cantwell Smith, who was the founder and the director of the McGill Institute, built and kind of envisioned what McGill was supposed to be in the 50's and 60's before he left for Harvard.

And he really built McGill from the ground up, the McGill Institute as a place of encounter between non-Muslim western scholars and Muslim scholars that he would go out and recruit from across the Islamic world, especially from South Asia, which is where his specialty was, but also from Southeast Asia - therefore Indonesians coming - because he really wanted this kind of fusing of, the merging of what he thought of as an academic, critical, social scientific approach to Islam with the insiders' impassioned, reformist energy of Muslims from the very recently post-colonial world. He had this quote that I like to think about. He said, "For western scholars studying Islam," - I'm just paraphrasing - "we can study the fish, the goldfish in the tank, we can count their scales, we can kind of see what color they are. But the problem with Western scholars is that they're not thinking about what it's like to be the goldfish."

And so Smith thought that in order to kind of cultivate good western scholars of Islam, you needed Muslims studying alongside of them to get them to be more empathetic, to get western scholars to kind of think from the inside of the Islamic tradition. So he really partly was recruiting Muslim scholars into McGill in order to improve Islamic studies from a western academic perspective. But he also was recruiting Islamic scholars from Southeast Asia, Iran, et cetera, because he thought that McGill could become, in his words, a midwife for the Islamic Reformation, that it could bring the best and the brightest from these Muslim countries, train them in academic methods, and then send them back to their home countries to establish new institutions to lead to become major political leaders, et cetera. And Smith was interestingly, really attached to sending his Muslim scholars from McGill back to Pakistan, Indonesia, Iran, so that they could foster this reformist revolution. So really the buildup of McGill, at first, I thought it was just a strange coincidence that all these Indonesians ended up in McGill, but it was actually part of the design of the McGill Institute of Islamic Studies to become this kind of place for empathetic studying of Islam for western scholars, but also this kind of hotbed of reformist thought for Muslims from across the Islamic world.

Kristian Petersen:

And how were these Indonesian scholars received when they came back? What was their welcome? How did the Indonesian public see their authorization through western academia?

Megan Brankley Abbas:

Yeah, so really interesting and kind of complicated question. So on the one hand, because the Indonesian government at that time period, so the book predominantly is looking at the 1960s, the 1990s, which is the Suharto period of Indonesian politics. So Suharto was a right-wing, pro-American, anti-communist military dictator, and he really kind of banked his authority on economic development in Indonesia and western style economic development, kind of in alignment with the United States. And as a result, the Suharto government was quite friendly with these McGill and the other western academic graduates coming in and kind of taking over positions in Islamic political parties, Islamic institutions, because the Suharto government saw them, since they were trained in the western academic tradition, most likely more friendly to western style development. So as a result, a lot of the McGill alumni have these really fast rises in Indonesian political hierarchies.

One of them becomes the Minister of Religious Affairs in 1971. Another one becomes the rector of the state Islamic University in Jakarta, which is one of the largest Islamic universities in Indonesia, and is able to rewrite not just the Jakarta curriculum, but the curriculum for the whole nationwide system of state Islamic universities. So from the perspective of the Indonesian government, these fusionist graduates from McGill in particular are seen as really in line with kind of a developmentalist western style regime under Suharto. But then from a kind of broader perspective of other Indonesian intellectuals within the Islamic tradition, these folks coming back with, instead of traditional training, either in Indonesia in pesantrens, which is the Indonesian term for Islamic schools, or going to Egypt or maybe Saudi Arabia, and getting what are seen as the more expected way of establishing your Islamic authority, coming back instead with Western PhDs was often quite controversial.

There were often accusations coming from other Indonesian Islamic intellectuals that these western PhDs had kind of sullied or tainted the way that the fusions were interpreting Islam. They were bringing in things from outside of the tradition, things that were inauthentic or kind of alien to Islamic studies and kind of imposing them on Islamic curriculum, Islamic schools. So the fusionists have both a large degree of political authority, but also have this kind of uphill battle that they have to climb to prove that their fusionist techniques are not inauthentic or are not outside or alien to Islam, but are actually something that can be grounded within the tradition itself and help the Islamic tradition thrive in Indonesia.

Kristian Petersen:

As the decades pass, we have a second generation of Indonesian scholars this time going to the University of Chicago, and again, returning home, often achieving prestigious positions. Can you talk about this kind of second wave and perhaps some of the continuing goals of this cohort and how shifting attitudes about western education are taking shape within Indonesia?

Megan Brankley Abbas:

Yeah, sure. So to me, so the second wave really picks up in the late 1970s. And as you mentioned, I'm really focusing on three major Islamic scholars in Indonesia. So two of them who became chairman of Muhammadiyah, this huge sprawling modernist Islamic organization in Indonesia, and another one who became a household name, really kind of like a public intellectual who had his own radio shows and was interpreting the Quran and writing a lot, and actually almost was a candidate for president in Indonesia temporarily. So these folks were traveling to Chicago in the late 1970s. And the thing that, to me, struck me as kind of different than the McGill wave is that several of them were really focused on the social sciences rather than on history or on kind of Quranic interpretation. And that's because the Chicago professors who were receiving them and training them, one of them was a Pakistani intellectual Fazlur Rahman, who was trained in modern Islamic thought, and then the other was a social scientist, a political scientist to be precise, Leonard Binder. And they, together, these two Chicago professors were really working on how to think through what an authentically Islamic mode of development, political and economic development, would look like. What would it mean to kind of get conservative Muslims on board with political and economic development?

And as a result, these Indonesians who are coming to study with them, start asking those types of questions pretty explicitly and start writing dissertations on questions of Islamic development. So is democracy in line with Islamic values, are certain types of economic development in line with Islamic values? And these questions drive both their scholarship, while they're in Chicago, but also become then their launching pad when they get back to Indonesia since those questions are very kind of hot button issues in the 1980s and 1990s, in particular in Indonesia, of how should we kind of think about authentically Islamic model of development that will take some aspects, perhaps, of western style development, economics, political development models, but then really infuse them with Islamic norms and values and models as well?

Kristian Petersen:

The other really interesting thing that you do in this book is you take stock of how we might think about Islamic studies in general, and it's kind of emerging out of this back and forth that you see of these different approaches and there success and outcomes. Can you talk a little bit about this kind of intersection of Muslim scholars, North American, non-Muslim scholars, and what are the kind of possible paths forward in the study of Islam?

Megan Brankley Abbas:

Sure. Yeah. So overall, the history that I'm telling about these generations of Indonesian Islamic scholars who are coming to North American universities and heading back to Indonesia, to me the major takeaway of that is that this border between Islamic theology or Islamic politics, normative Islamic work, and the academic study of Islam has really collapsed. It's really hard to draw any distinct line at any time, for me, from this history of people who are doing normative reform work, both Muslims and non-Muslims, and people who are doing academic research that is more descriptive or objective or these words that people often use. And so to me then the kind of pressing question is, well, what do we do with this collapsing border or this collapsed border between Islamic theology, Islamic politics, and the academic study of Islam? And the conclusion of the book kind of proposes a couple of different ways of thinking about how we might, once we recognize that the border has collapsed, how we might respond to this.

So one of them is you could try to rebuild the border. You could try to say, okay, no theology in the academy, no academic methods in Islamic schools, and try to reestablish a neat bifurcation of the two. I think that that ship has largely sailed, and I think for better that ship has sailed. So I play around with that idea, but I don't really think of it as maybe a viable way forward.

The other two, I think, ways of thinking about this story and perhaps the way forward is to embrace the kind of plural discursive or the plural commitments that are in the academy. And instead of thinking that there are kind of set rules and methods that academics have to follow, to kind of pluralize the possibilities and to think about the university rather as, instead of having certain standard methodologies, instead saying, we are a place where people can come and debate what a proper methodology should look like, can experiment with entirely new ones, and to really just kind of let the academy be a space, rather than a set of rules for cosmopolitan, diverse, different ways of engaging with the Islamic tradition. And that, I think, has a lot of potential. To think the academy maybe is not purely "academic" in quotation marks, but instead a cosmopolitan, diverse, partly theological, partly non-theological space. So yeah, that's the second one.

The third, I borrow a lot from Wael Hallaq's book on Restating Orientalism that takes a much more pessimistic stance towards the academy and sees perhaps through Hallaq's eyes the story that I'm telling about Indonesia as a story of epistemological imperialism, academic imperialism, that the academy out of North America, especially the United States, has overreached its boundaries and has started kind of reforming Islam when it should not have much to say about Islam. That we should let Muslims reform Islam if they so desire, rather than kind of reaching out our hands and getting involved in internal Islamic matters. And Hallaq, I think, as a result, would tell us to really rethink these types of exchange programs, to really rethink the desire for academics to be involved in Islamic politics, to judge, to critique, to champion certain models of Islamic interpretation over others. And that really is a signal of academic imperialism. I personally find myself torn between model two and model three, thinking about the academy as a cosmopolitan space versus thinking about that cosmopolitan space as I think Hallaq would do, as a symptom of global overreach and imperialism.

Kristian Petersen:

It's definitely interesting context there, and I think certainly this last section, especially folks working in Buddhist studies and Jewish studies across the American Academy of Religion can really learn a lot and think about what they're doing. Even this divide not only between theologian and scholar, but perhaps this kind of identity as scholar activists and what might be the normative claims within methodologies there. There's a lot I think that people can glean from your work, so I hope they'll pick the book up. And I want to congratulate you again on the award, and thanks for making time to talk about your wonderful book.

Megan Brankley Abbas:

Yeah, thanks so much for having me.