The Contract Employee

I am an adjunct/contingent/contract employee at multiple universities. I recently decided names matter, because after years of teaching that words mask and reveal truths to my students, what I call the work I do determines how I see myself as an employee.

I am not an adjunct, yet. An adjunct is someone who teaches as a side job. A professional who wants to give back comes and teaches as an adjunct. Professional schools, like law, business, and medicine, may have adjuncts. Their pay as adjuncts are “thank you” gifts that acknowledge time, effort, expertise, and the fact that the adjunct has a full-time job. Therefore, I’m not an adjunct. I do not have a full-time job, and nobody in HigherEd is paying me enough for my time, effort, or expertise. Some places are not even paying me minimum wage, making me question how long they will last when people figure out Costco values us more than HigherEd does.

I am not contingent faculty. Contingency depends on a certain of conditions that make the temporary hire of workers necessary. With nearly 70% of faculty working as contingent hires, this is not a temporary or conditional state. Business as usual, and a strong emphasis on business, relies on decreasing labor costs, so part-time faculty define the modern university. The only thing contingent about my labor is how fast any university I work wants to prove their irrelevance and cut more positions that do not immediately train for yesterday’s jobs.

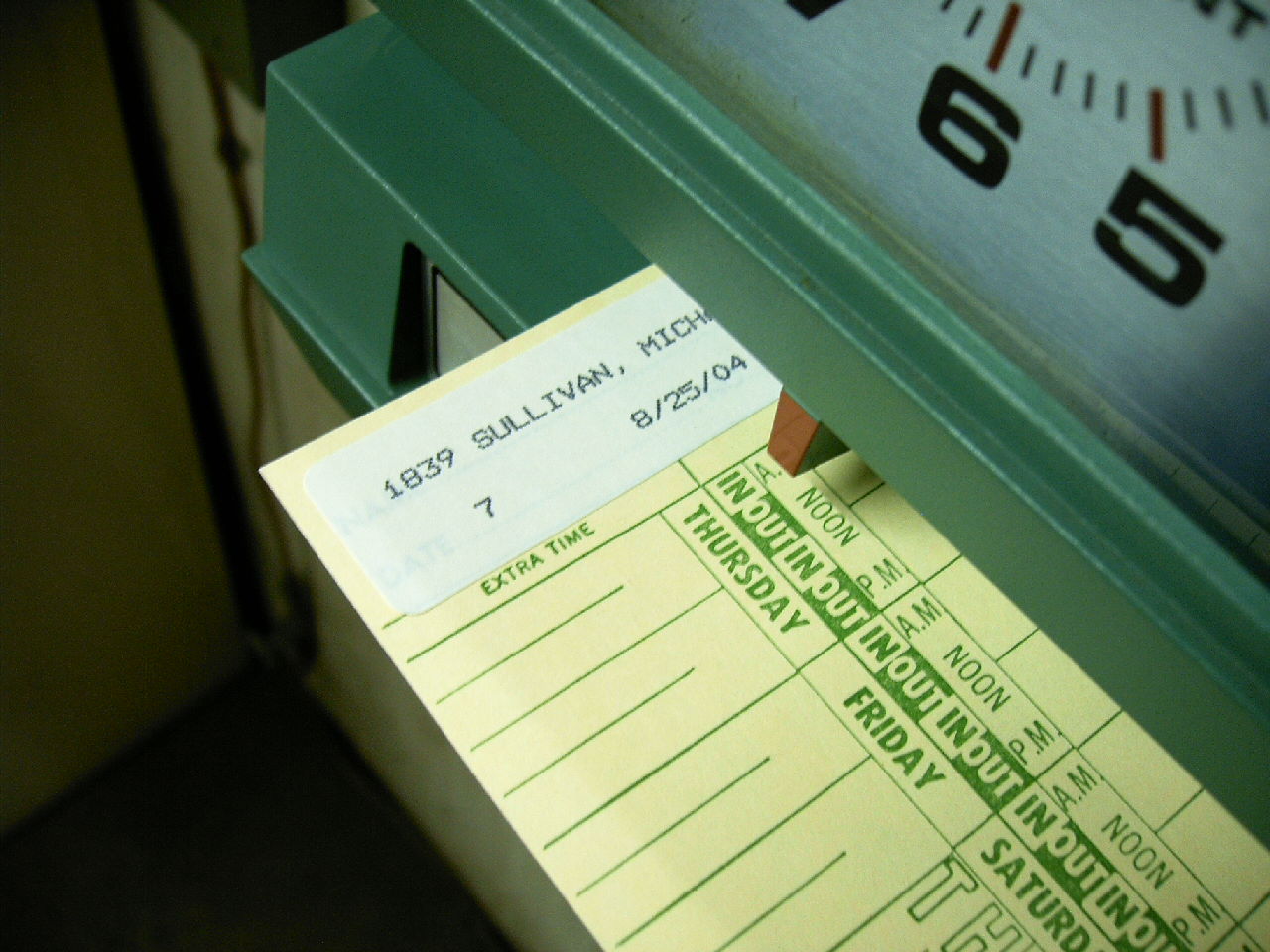

I am a contract employee. This is an important label. It means I can negotiate contracts. There are limitations within each university, but generally, I do what the contract says and nothing more. There is no work that is implied or expected; contracts do not work that way. I had one school that ended my contract on a date before finals began, so I refused to administer the final without being paid. The union said the administration had every right to expect work outside of the contract, so they were no help to labor. They failed to realize that I would not be available for grade appeals either, since I was no longer an employee of the university, and there was no clause in the contract to account for appeals. I am not sure the school understood that it is potentially a FERPA (Family Education Rights and Privacy Act) violation to give me access to student records when I am no longer an employee.

As a contract employee, I can decide what is worth my time and what is not. I can show very clearly that the hours a school expects for classroom instruction, preparation, and office hours is close to minimum wage, if not under it. Any time a school asks me for something, I can ask for money for it, because it is not in the contract. The new faculty majority is a freelancer’s group, and we need to start asking for what we believe we are worth.

Thinking about myself as an independent contractor returns agency to me. I can say “no” to schools because their pay scale is not just cheap, but immoral; or because they run industrial-size classes that exist simply to bring in tuition; or because the contract hides work under the expectation that’s what good scholars should do. Good scholars should teach and research, and when we allow systems to grow that prevent us from doing so, we are no longer being good scholars.

Names matter, so I tell my students I am a part-time contract employee. I tell them I love to teach, to learn, to be part of a community of like-minded people, but I have to work to be able to afford to teach them. And that is our first lesson on the power of names and of capital.

Hussein Rashid is a member of the AAR's Contingent Faculty Task Force and a contract employee currently affiliated with Hofstra University.