A Conversation with 2016 ALHR Lecturer, Dr. Fatemeh Keshavarz

The American Lectures in the History of Religions (ALHR) is proud to welcome Dr. Fatemeh Keshavarz (University of Maryland) to speak in a series of public lectures in the Chicago area from October 24 to the 28, 2016. Dr. Keshavarz’s lecture series is entitled Unsilencing the Sacred: Conversations with the Divine, and in them she will explore the works of poets such as Omar Khayyam, Hafez of Shiraz, Sa’di, Jalal al-Din Rumi, and ‘Attar of Nishabur.

In addition to her lectures in Chicago, Dr. Keshavarz will offer a general summation of her series at the 2016 AAR Annual Meeting in San Antonio, Texas, on November 20.

Listen to Dr. Keshavarz's podcast, Radio Rumi via iTunes or University of Maryland.

As you know, the ALHR has been hosting lecturers since the late 19th century. From its earliest lectures, the ALHR explored various topics, with Buddhist, Egyptian, Japanese, Vedic, “Primitive”, and Persian religions all discussed in just the first decade. What do you think is the significance of continuing an exploration of ancient texts, specifically in the Islamic context?

The significance of exploring these ancient texts is immense. For one thing, the exploration helps us see the continuity in the human engagement with the larger questions of life. Our desire to make ourselves better, to love, to learn, and to create are not modern phenomena. It is important to see that first hand through in-depth engagement with these texts. Furthermore, our digital brains are now being trained to think of texts only as repositories of information. As a result, we get more and more used to skimming the reading before us for “relevant” information instead of developing more long-term ties with such texts, savoring their beauty, creativity, and depth. The exploration of ancient texts, to which you have referred, helps us to move beyond the surface and seek more than a rudimentary process of information gathering.

All of the above become especially significant when it comes to primary ancient texts that were produced in the Islamic context. By virtue of being preserved in less familiar languages, and being produced in less explored (and often misunderstood) cultural contexts, these texts are not taught or read as often. Much treasure is there to be discovered and savored: treasures of beauty, creativity, emotive expression, analysis, struggle, thinking and more.

Dr. Fatemeh Keshavarz, Director, Roshan Institute for Persian Studies, University of Maryland. 2016 ALHR Lecturer.

Dr. Fatemeh Keshavarz, Director, Roshan Institute for Persian Studies, University of Maryland. 2016 ALHR Lecturer.In the months prior to speaking at the UN General Assembly in 2007, I lived in the constant terror that the US military intervention in the Middle East will soon spread further and reach Iran. Besides my very personal feelings arising from the fact that I had been born and raised in Iran, I found such a situation totally lethal for the region. I had just published my book Jasmine and Stars: Reading More than Lolita in Tehran to counter the narrative that Iranians were either villains or victims. I wanted the world to see and appreciate the complexity and the potential of Persian culture as a positive presence on the global stage.

I was delighted with the invitation to the UN’s Assembly and the fact that a few of us scholars had been asked to address the significance of cultural education for world peace. I had not even had the time to think about how thrilled I would be when Secretary General Ban Ki-moon shakes my hand. Well, I was.

I focused my presentation on the ways in which the peoples of the Middle Eastern and Islamic origin have been distorted and turned into ghosts. They are often othered and often demonized in vague and general terms. They feature in the media as unknown masses that cause terror. And yet, like ghosts, they do not have faces, names, or individual stories. I proposed that the UN put serious efforts into training its own young cultural ambassadors by providing encouragement and resources and lending the prestige of its name to countries that are happy to empower their youth to learn languages, travel worldwide, and fight our global ignorance about each other.

I think this kind of hands-on cultural education is needed even more today to counter ignorance, isolation, and the resulting tendency to resort to war and violence.

Your work has spanned across a variety of poets and mystics. Do you have a favorite author or work? If so, what specifically draws you to that author or work?

This is probably one of the hardest questions for me to answer. I have lived among a constellation of star poets whom I have loved and enjoyed all my life. American poets have been added to that list over the past few decades. These including Billy Collins, Mary Oliver, Stanley Kunitz, Galway —Kinnellto just name a few contemporaries.

But since you are addressing my own work, the first mystic poet whose work I studied and wrote about (in English) was Jalal al-Din Rumi (b. 1207). I still think that he is one of the most vibrant, profound—and at the same time playful—presences that we have on the world’s poetry scene. His lyric poetry, contrary to what we expect of this genre, is direct, dramatic, and able to make you dance. I mean this in a literal and metaphoric way both. Literally, he gives us some of the most musical verses you can think of in Persian language and encourages you to join the whirling dance as you listen to them. Metaphorically, he wants you to get off the margins of life and join the big whirling scene which is the universe. You have to be in love or your existence matter little. “If you do not have that fire, descend into nothingness!” is a translation of a famous verse from the opening lines in his major book of speculative mysticism in rhyming couplets The Masnavi. Interestingly, Mary Oliver has an exact—almost word for word—rendering of this thought in her poem “What I Have Learned So Far” in which she ends the poem with “Be ignited, or be gone!”

I absolutely love Rumi’s work and can continue to write about him perhaps all my life. But, in a way, when I finished my book on his lyric poetry Reading Mystical Lyric: the Case of Jalal al-Din Rumi, I was aware that this great attraction could become a prison. I could easily become a Rumi person, if you like. There were so many other Persian poets whose work had filled my life/imagination and inspired me from childhood that I wanted to write about them as well. The Persian ghazal-writer par excellence Sa’di of Shiraz (b. 1203) was the one I started exploring next. He seemed to have developed an unjustified reputation for being a master versifier and a dry moralist among the 20th century critics particularly inside Iran. That was not the Sa’di I had known. I enjoyed the freshness, the humor, the practicality of his way of looking at social and ethical issues. People often think Rumi is ecstatic and Sa’di is all law and order. That was not my feeling at all. To me, he is as exuberant and love-stricken. However, like his poetic language, his universe is neat and orderly. The play between these two seemingly conflicting sides turns his poetry into a colorful melodic symphony that is about coming together one minute and spreading out the next. What you know at all times is that a powerful composer has carefully crafted this masterpiece and set it to motion. I published my monograph on him Lyrics of Life: Sa’di on Love, Cosmopolitanism, and Care of the Self last year. Now, I am trying to resist the temptation of becoming a Sa’di person so I do not close other doors on myself!

What aspects of the poetry of mystics, such as Rumi and Hafez, do you think allows them to be so easily integrated into popular culture?

There are many, of course. And, needless to say, like other poets, mystics have their individual experiences, historical contexts, personal temperaments, and particular abilities with language. But if we were to make generalizations, a few characteristics would stand out. For example, these poems value personal encounters with life, “tasting” the joy of connecting with “the Real,” “the Friend,” the beloved,” “God,” or whatever you choose to call that which we all crave for. Because experiential learning is important, shocking the reader and giving him/her a sense of surprise, joy, and elation is more important in these poems than lecturing on ethical and/or philosophical aspects of spiritual development. This methodological preference for “tasting” mystical learning automatically privileges the ability to remain joyful, vibrant, and receptive in comparison to pedantic gathering of knowledge. Please note that I do not intend to down play the significance of speculative knowledge for these poets. Rather, I wish to show a trend that makes the poetry of these mystics accessible to none-specialists.

At the same time, attaching value to the simple human ability to connect with the higher forces of goodness—regardless of the religious rubric used to refer to these forces—allows for a distinctive level of openness and tolerance for those who are not like you.

Last but not least, mystic poets of various traditions incorporated music and dance into their practices. Their poetry was often sung to music even by those who did not formally carried membership in a particular Sufi/mystical order. Besides creating a joyful atmosphere, these musical performances overcame the linguistic barriers that usually prevent people of diverse background from communicating effectively with each other.

Do you have any books you would suggest for “beginners” interested in exploring Persian poetry?

All right, I’ll be shameless! To begin with, I recommend my Jasmine and Stars: Reading More than Lolita in Tehran. Of course, when you go to Amazon, or other online vendors, you’ll see reader comments and it can help you see if this is the kind of book you are looking for.

The reason why I recommend it is that I wrote the book to show that Iranians have gone, and still go, far beyond Reading Lolita in Tehran, and that a good deal of what they read is poetry. In the process, I speak about this poetry and give examples. I also think the book is helpful because a fair amount of cultural context is explained in the references to Persian poetry. Last but not least, I wrote the book with the general, educated, nonspecialist, American audiences in mind and in order to counter the minimalist, misinformed, and at times hostile portrayal of Iranians. Therefore, the book focuses on the joy that the literary, particularly poetic, aspects of Persian culture can bring to people’s lives.

Beyond the kinds of reading that familiarize one with the distinctive characteristics of Persian poetry, I would emphasize reading the poetry itself. For example, I would highly recommend In the Dragon's Claws: The Story of Rostam and Esfandiyar from the Persian Book of Kings translated by the late Professor Jerome Clinton. The Book of Kings is the foundational myth of the Persian culture. This excerpt is the story of the fight between two major heroes in the book. It is masterfully translated into a rich, humorous, and thoroughly readable English. There are other translated texts that I would recommend. For example, Selected Poems of Rumi translated with an introduction by Reynold A. Nicholson. I would also recommend Bride of Acacias, a masterful translation of the works of the 20th century Iranian poet Forough Farrokhzad by the late Amin Banani in collaboration with an American poet Joshua Kessler.

But above all, to all interested in Persian poetry or poetry in general, I recommend learning the Persian language. It is a relatively easy Indo-European Language which will give the learner the beginnings of access to a treasure-trove of poetry after a mere two years of diligent work.

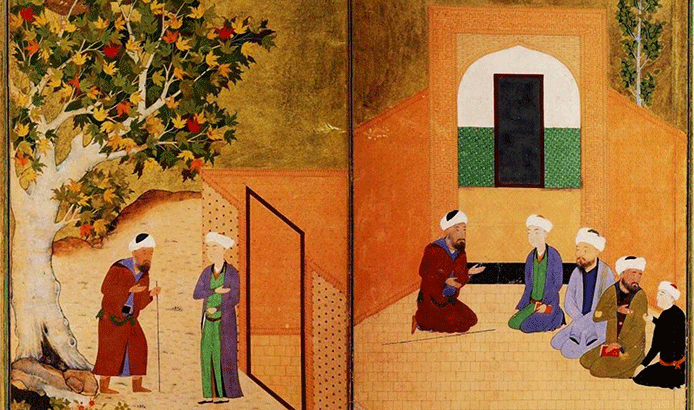

Image: Saadi [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons