Film as Methodology: Torang Asadi on Ethnographic Filmmaking in the Study of Religion

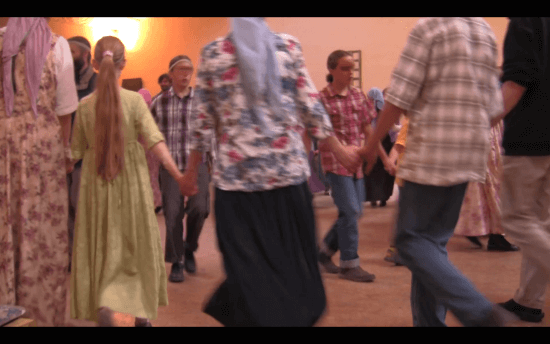

Being seen by God. Screenshot from raw ethnographic film, Torang Asadi

Torang Asadi is pursuing a PhD in religion and modernity at Duke University, writing her dissertation on religion in the Iranian diaspora. Asadi's research is firmly based on the close relationships she develops with the communities she studies and documents. She began developing her skills as an ethnographic researcher and filmmaker as a master's student and continues to champion the medium as a legitimate and productive method of research. In this interview, which was conducted via e-mail and has been lightly edited, Asadi discusses objectivity, methodology, ethics, and legitimacy in ethnographic film.

Sarah Levine: How did you first become interested in studying religion? When and why did you begin using film as a medium to study religion?

Torang Asadi: I graduated with a double major in pure mathematics and interior design. I discovered religion only in the very last semester of college, when I took a course on new religions with Becky Moore. It was during a field project for that class that I realized I needed to pursue this field. I grew up in Iran, where my mother attended underground classes in New Age philosophy and meditation, so my own experience with religion was quite bizarre. I was too intrigued to be content with a PhD in mathematics or a career in design, so I strayed and have never looked back.

I became interested in film as a medium during that same semester. I spent most of my time watching audio and video footage from Jonestown, Heaven’s Gate, and the Manson Family. There was an aspect of the human experience that could not be conveyed through text as secondary source, and an authenticity to the footage as evidence. During my master’s program, I began to take courses in the film department to develop filming and editing skills, and I worked with anthropology professors to both train as an ethnographer and think through theories of film as ethnography.

Do you think it’s important for scholars of religion to take film seriously as a research method?

Absolutely. Evidently, when we talk about ethnographic films, we are talking about work on contemporary lived religion. But there is not much engagement with film, even in that subfield. Anthropology has made a lot of progress in that direction, but religious studies remains far behind in modern methods of research. Why wouldn’t you use film, especially in the study of religion?

The subject of our study is the unique experience that can only be explained through an understanding of the community in which it is conditioned. And the religious space is unique in that it is not readily accessible. So if we have the privilege of being present and conducting research in that unique space, why not engage a medium that can more honestly communicate that experience? And many would argue that it is not a more honest medium, which I think has to do with vision as a continuous sensory experience, which film interrupts, and speech as fragmented by nature, which text preserves. But that's a separate conversation altogether.

It’s such a great teaching tool, too. In religious studies, we have already moved past the written text as the primary subject of study to lived religion and materiality. So why can’t we do that with our research methodology as well?

Do you use your films in your classroom teaching? As a producer of ethnographic films, do you have any insight for teachers who might want to use your film or others like it in the classroom?

To my surprise, I’ve learned that students don’t like to watch too many films in class. I’ve also learned that they don’t like the traditional documentary format and get bored very quickly. The moment I realized I wanted to do away with commentary in my own work was also the one in which I realized that my students were unusually engaged with Peter Adair’s Holy Ghost People, a 1967 film about snake handlers. When the professor I was TAing for assigned the film, I thought the students would hate it. The footage is very rough, in black and white, and the audio quality isn’t great. But they loved it! The experience of that community felt authentic to them. It was very obvious from the final exams that the film was memorable for every one of the students. And they were all very aware of themes like leadership, personal engagement with the divine, and physical reaction to salvation. They had also picked up on one the most important moments: the fall of the prophet. So we were also able to have a very lively discussion about it. The traditional documentary acts as a textbook for them, but the ethnographic film feels more like a field trip.

I’ve also experimented with having students watch films at home, but engage in a discussion about it in class while the footage plays on mute. It’s been very useful to have the visual present during conversation.

In short, I think the best film for the classroom is one that shows the student a specific human phenomenon, and even maybe hints at certain themes and conveys an analysis; not the one that tells them what they need to know about something. The former is the kind of film that provides an opportunity for an essay question on an exam; the latter gives you a fill-in-the-blank at best.

In our initial exchange you mentioned some obstacles you’ve encountered while working with film. Can you elaborate some of these—perhaps the logistical, ethical, and/or financial?

Ethical and financial obstacles are always aplenty. Camera equipment and editing software cost quite a bit, as does travel for acquiring the footage. And the process of obtaining proof of consent is traumatic. Getting the permission to film is the worst of them all, because there’s so much to it: gaining trust, making the case for your project, speaking to the right people, informing every member of the community of your project and intentions, securing access multiple times, knowing what you can and cannot film.

But the methodological issues are more productive to discuss and work through. For example, I’m very interested in the material or embodied religious experience. I’m interested in how space, place, and atmosphere are experienced. How the body moves, stays still, how it’s disciplined. How it engages its surroundings and acts differently when not in the sacred space. And this is not very easy to convey through film. For example, an important part of the religious experience in a church is sound. How can you ignore the echo in a church? Every time you shift or fidget in your seat, you hear it and are aware that everyone else hears it as well. Every whisper, every crackle, every chuckle echoes in there, and that itself regulates the body in a certain way. But you need expensive audio equipment to record and convey the echo and enough experience and a good theoretical approach to capture the way this sound

BAPS Temple, Raleigh, North Carolina. Screenshot from raw ethnographic film, Torang Asadi.

BAPS Temple, Raleigh, North Carolina. Screenshot from raw ethnographic film, Torang Asadi.Are there any issues on the other side of the camera?

People act differently when aware of the camera. Religious communities never forget its presence, because it’s threatening, especially for more marginal communities. The camera captures an extremely intimate and totalistic part of their lives.

It’s important to have accomplished solid ethnographic work prior, so that the ethnographer can identify the differences in performance and judge her own footage’s validity. Most times you will know when your interlocutors are acting differently. I discard a lot of footage because I can tell it’s not natural, for example, when no one’s entering a trance-like state when dancing at a New Age chanting event, when they would if the camera weren’t present. And that’s why it’s important to have hours and hours of footage and to keep going back with the camera. I think out of every ten hours of footage, there’s ideally an hour of natural footage, and it’s up to the ethnographer to determine the nine hours that are problematic. There have also been times when I haven’t been given permission to film in a particular space or to return to one to obtain additional footage.

I don’t mean to distract from the value of film by talking about all the issues and obstacles. The fact that such issues exist and the fact that we can have this conversation and try to find solutions to these obstacles means that the medium is worth working through. We can pose the same types of questions to our own method of written scholarship. Many claim that film is not a reliable form of scholarship because a lot ends up on the cutting room floor. My response to that would be: first, the cutting room floor is now a folder called “raw footage” and is as accessible as fieldnotes, primary sources, and secondary sources used by any author. And second, there is no difference between editing footage and editing an article. In short, they are both edited and much of the information is left in a research folder somewhere. That is why we have the peer review process. As a matter of fact, even selective and edited footage is more reliable than the fieldnotes and the speculative analyses that make up the material from which we weave written scholarship. And again, this is still a topic of much debate, but the short version of the claim would be: it's much easier to fabricate and manipulate fieldnotes. At the end of the day, the obstacles are not that different from the ones we face as ethnographers.

Do you see a close connection between ethnography and film?

That is perhaps the most important connection when thinking of film as a research medium. You need to know the community well enough to know where to point the camera, and you need that familiarity to be able to have a camera present and to gain permission to publish your work. You need to know the validity of your footage and be able to measure its honesty. The best thing film can do is convey the experience of the ethnographer, who is a trained professional. And that is what academic scholarship is supposed to do, as well. It is, first and foremost, the ethnographer who can provide an understanding of a community, not the filmmaker.

Ethnography is a very delicate endeavor. It’s one thing for scholars to visit a community, ask some questions, and write up some field notes, but it’s another for an ethnographer to pay extremely close attention to her own body, its relation to other bodies, the ways it morphs as a result of living with that community, and the way in which the community's response to her body’s presence changes over time. For anthropologists, it is unimaginable to spend less than a year in the field or to conduct your research through a translator. But our scholars even get away with just a few hours of face-to-face time, if any, with the people about whom they write. Despite the hopeful move toward ethnography, language competency in our field is still equivalent to reading knowledge of research languages. Ethnography is absolutely crucial to our research of lived religion, and it’s something that takes a lot more than a few visits to accomplish.

A good example is when a community feels the right to correct the ethnographer, which means she’s no longer a stranger and that she has a responsibility to this community now. This dynamic is very fruitful, but takes a long time to achieve. I’ve been spending time with the Twelve Tribes Community for over six years now. I dress differently when I visit one of their communities, out of respect and to create a more comfortable presence, especially for the children. I am covered from neck to toe and my clothes have more room than my body requires. During a visit to one of their communities in France, a few of the women around me leaned in to let me know that the top button on my blouse was undone and that they could see my skin. “Let me know if it’s broken, I have a pin,” one informed me. It was clear that I was being instructed to cover up, and that was extremely exciting! There's a lot to discuss here regarding ethics, but the fact that they felt the right to correct me and not the other guests meant that I was part of the community, enough to be held responsible and corrected. There was so much for me to learn in that moment, and I was much more confident in my ethnography.

But place a camera in my hand and everything would have been different. There is no way I could have gained the access, trust, and understanding that participant observation provides with recording technology, and even less so with a camera crew. I did, however, bring my camera out about a week after that incident. And I was allowed to film almost everything. After a few minutes of showing the small consumer camera to the children and even letting the curious members play around with it for a bit, the comfort they felt with me overshadowed their enchantment with the object and I began filming. Being an ethnographer first and an ethnographic filmmaker second is absolutely crucial, I think.

How does your methodology as an ethnographer translate into your methodology as a filmmaker? Do you theorize the two in the same way?

I’m very interested in the material religious experience, which is more than the simple engagement of objects. I’m interested in embodiment. How the body moves, stays still, and is disciplined. How it engages its surroundings and is different when not in the sacred space. How it becomes the technology through which religious work is done and made efficacious.

Even in my ethnographic method, I pay close attention to both my own body and the bodies of my interlocutors. Together they form a very complex relational network. So I work very closely with theories of the body, conduct my ethnography through the body, and film with a similar approach. That is another reason I make minimal use of fancy equipment and see the presence of a crew to be detrimental. For me, my small camera is part of my ethnographic body. It's more of an appendage than a tool, and creates a collective whole that affects my presence and my engagement of the community. It changes the way I move, the things I see, the things I remember, and the way I am received, regulated, and included.

Are there things you learned from filming your subjects that you might not have learned from merely observing them and producing a written ethnographic analysis?

Absolutely. I have so many examples. I work on the counterhegemonic tensions that make room for innovation, so I work with communities that have rebelled against what they have recognized as corrupting powers. And seeing a community’s reaction to what the “outside world” will be seeing of them is illuminating. What they allow you to film and when they ask you to put the camera away tells me so much about how they demarcate themselves from the world. Also, the camera can stare, but I can’t. So hiding behind the camera and focusing on something specific has been very fruitful. The way communities interact with the technology, the spaces they allow the equipment in, and the things they stop doing in front of it are just a few examples of what you can only pay attention to with a camera in hand. You also end up recognizing space, light, and sound differently as a filmmaker, which can also teach you more than you’d expect.

There aren’t too many established scholars who use film in their academic work. You’re studying at Duke, and I imagine that was a calculated choice.

At Duke, I was recruited by David Morgan, Ebrahim Moosa, and Leela Prasad, who encouraged me to incorporate film into my work. However, that encouragement was very unique to this group of professors. And I am still being encouraged to submit chapters of my dissertation as film. I did not get the same reaction from other institutions, such as Harvard. One of Leela Prasad’s students submitted an entire MA thesis as film, with accompanying commentary. Duke also has a fantastic program in documentary studies. So I’ve worked with Gary Hawkins and Steve Milligan, both of whom are fantastic.

In our own field, the incorporation of film has been pathetically slow, but not absent. But there’s hope, it seems. The current editor of JAAR, Amir Hussain, came to UNC-Chapel Hill last year for a great session with graduate students and he did mention that he’s hoping for submissions that engage ethnographic film in some way.

Who else in the field is engaging documentary filmmaking as a scholarly enterprise? Where is the theory happening?

The shift towards lived religion, material religion, and understanding text as much more than the written word is not new anymore. Our field is no longer limited to textualists. This is a debate that has run its course and impacted our field in a fruitful and progressive manner. But we still don’t have the right training to compliment this trend. We are just now seeing ethnography courses in religion programs. Graduate students are still tested for reading knowledge in their research languages, with not much importance being given to their ability to converse with their interlocutors in their own language. And the primary form of scholarship is still the written one. Our training has not caught up. Film as a research method and as academic scholarship is still a distant hope. We have a lot of catching up to do with anthropology in that regard. [Editor's note: The American Anthropological Association has had "Guidelines for the Evaluation of Ethnographic Visual Media" since 2001. They were updated in May of this year.]

There are scholars who have engaged ethnographic film in their own work. Jeffrey Kripal and Leela Prasad are the better-known names that come to my mind. Most ethnographic filmmakers right now are anthropologists studying religion, not religious studies scholars. But just to be clear, we’re talking about ethnographic film, not documentaries like the ones produced for Diana Eck’s Pluralism Project. The goal is the ethnographic documentary as scholarship; one that does the same work an article or book would do in our field.

The theory is not happening in our field; it’s happening in anthropology. There’s a fantastic edited volume by Peter Ian Crawford and David Turton. There’s also the work of David McDougall and Anna Grimshaw. There is a great Oxford Bibliography, which is a great place to start. I’m also very interested in the sensory experience, and pay attention to affect, which is very hard to film. Laura U. Marks has a couple of pieces that discuss the senses in haptic images and embodiment that I would recommend.

The Twelve Tribes Community, Klosterzimmern, Germany. Screenshot from raw ethnographic film, Torang Asadi.

The Twelve Tribes Community, Klosterzimmern, Germany. Screenshot from raw ethnographic film, Torang Asadi.You reference Eck’s documentaries. Can you elaborate on the distinction between ethnographic film and documentary? And can you give some examples?

A “documentary” is very personal and creative, and not academic. It’s nonfiction, but still narrative and artistic in nature. On the other hand, there are documentaries that are characterized by the Ken Burns Effect, expert interviews, and monotonous narration.

“Ethnographic film” is footage obtained during ethnography. It’s most useful to think of it as raw footage, like fieldnotes. Watching ethnographic film is like reading someone's field notebook.

“Ethnographic documentary” is equivalent to the finished scholarship. The same way that a scholar uses field notes to write an article or a book, he can use footage to make an ethnographic documentary, which is academic in the sense that the scholar’s analysis and research are brought together in a film.

These aren’t necessarily useful distinctions, to be honest. The main goal is to have a polished product that serves as scholarship. The simplest form would be the written scholarship orated over ethnographic footage, but that’s just boring. And going back to the classroom example, it’s not successfully educational.

Philip Gröning’s documentary, Into Great Silence, about the Grande Chartreuse is a great example of an ethnographic documentary. It took him 16 years to gain permission for filming. He spent a year living in the monastery with no camera crew and the bare minimum in terms of equipment. That film is purely ethnographic in that sense. It’s not ethnographic footage, since it’s been beautifully edited, but it’s also not documentary since it conveys a purity to the experience. And I don’t mean that there is a lack of editing, just that the film is not unnecessarily embellished.

Lucien Castaing-Taylor’s work also comes to mind in this regard. This intersection is what I think of as an ethnographic documentary: one that is ethnographic in nature, but edited and polished; the sweet spot between raw footage and a work of art. The ethnographic documentary can be academic scholarship, and it can be made for public consumption as a standalone project. As a matter of fact, it is more valuable since it would be more accessible to the public. But I think this is the issue we’re facing right now: how do we engage academic theory in film?

Right, so if there is no narration, then how does the scholar engage theory or provide analysis through film?

The easiest answer is commentary, since divorcing scholarship from the medium of the written text remains so difficult. But the narration, for me, is always like a paper being read at a conference: I’d much rather have that paper to read in the comfort of my couch and pajamas. But how do you make the ethnographic documentary as efficacious as the written scholarship? How do you include analysis and engage theory without speaking it?

The closest I have come to this goal is trusting the viewer to make the connections implied in the footage itself, the title, interview material, candid conversations, and perhaps a couple of sentences of text when absolutely necessary. For example, I was working on a short project tilted “The Distant Touch and the Material Gaze in a BAPS Temple,” and the footage is very much focused on the human body, especially the hands, as ritual technology. It is also focused on the positioning of the body in relation to the murtis, and how devotees look at and are seen by them. So you can expect a lot of closeups from the ways in which devotees use their bodies to pray or address the murtis from a distance. The reciprocity of the gaze and the inability to touch the murtis is also explained visually through the film by a devotee as she silently walks around them but keeps her distance.

Interviews often do some of the work for you in this regard, but the traditional interview format feels unnatural and is not purely ethnographic to me, for some reason. It feels set up, both by the interviewer and the interviewee. The most successful and enlightening interviews I’ve had have been while washing dishes or mopping floors with the members of a community, not when I have them seated in front of lights and cameras.

So to answer the question: I don't have an answer. Just like written scholarship, it depends on the scholar to choose a writing style and to format the analysis. I think this question, of making film academically theoretical and analytical, is one that needs to taken up by scholars of religion, because that's how we can work through adopting film as a productive method of both research and scholarship.

If you were to pinpoint the most valuable aspect of film as scholarship, what would it be?

There is an important question that I ask myself with film: If you can’t say it through images of the community and through its members, is it worth saying at all? How much of our analyses is made up and conjectured? If you can’t say it with film, does that mean it’s too far removed from reality? I’ve never been one for over-theorizing or abstraction beyond recognition. If the people about whom I write cannot relate to the scholarship, is there a purpose to my work?

Leela Prasad demonstrates this very well in her Poetics of Conduct. She questions the categories she's trained with, prefers the language of her interlocutors to that of the disciplines, and engages her subjects in a conversation with the scholarship itself. I think it's no coincidence that she also works with film.

You can write something your subjects don't understand, but it's much harder to make a film to which they can't relate (assuming dishonesty is not a factor). So, a lot of times if I think it can’t be said through film, it must not be said at all. Ethnographic film has a way of pulling me out of an academic cloud of abstraction down to the reality of the human phenomenon that I’m studying. In that sense I think it’s very valuable as academic scholarship.