Sandwiched but Not Smashed: Connection, Loss, and Responsibility in the Middle Years

Almost twenty years ago, when considering pregnancy a subversive state bearing “generative lessons unknown to men and angels,” I made the following remark: “Serious involvement in child bearing and rearing involves an . . . unrelenting tug of attachment, what Kristeva calls a pain that ‘comes from the inside’ and ‘never remains apart. . . . You may close your eyes, . . . teach courses, run errands, . . . think about objects, subjects.’ But a mother is marked by a tenacious link to another that . . . never quite goes away .” (Miller-McLemore, Also a Mother, 143. See also Julia Kristeva, "Stabat Mater," in The Kristeva Reader, ed. Toril Moi, Columbia University Press, 1986: 166)

I never anticipated how true these innocuous words would become—a mother is marked by an unrelenting tug of attachment that never quite goes away. Nor could I foresee how workplace and family responsibilities would expand rather than diminish as the years roll by. My children may actually produce children of their own and I’m still not sure I can handle the complexity of my life, much less this reproducing and doubling of relations and obligations.

The question is: How do women in academe in the middle years deal with this tug of multiplying responsibilities? Is there a way to be “sandwiched” but not smashed? Apart from thinking about early mothering and adult vocation, I claim no special expertise here. I imagine there is a substantive social science literature worth considering. The privilege of my own situation may even block my insight — I have a job and financial resources, a partner who shares household work, three sons aged twenty-two, twenty-four, and twenty-seven years whose biggest problems are typical of what experts call “emerging” adulthood, and my parents remain relatively healthy in their mid-eighties. I no longer face daily unrelenting choices between children and work and I have yet to assume the arduous leave-taking, body-tending, and home-rearranging demands of sick and dying parents.

There are nonetheless issues I can name. Although the challenges are less immediate and urgent when children become young adults, the pain and angst do not simply dissipate. I used to get irritated by my mother-in-law who seemed to worry excessively about her adult sons. My mother frets over my siblings’ failed marriages, financial hardships, and vocational pressures. I swore I would not do that. I have had to eat my words. I have not completely forsaken such emotional labor. And now I also worry about my parents, although they probably wouldn’t like to know that.

After you spend a major portion of adult life protecting and providing, parental empathy (that uncanny life-sustaining ability to enter into another’s world) doesn’t just evaporate. Pregnancy is suggestive, as I argued years ago. “In the pregnant body the self and the other coexist. The other is both my self and not my self, hourly, daily becoming more separate” until the child, once physically part of me, waltzes free, moving out into the world (Miller-McLemore, Also a Mother, 143). No wonder mothers find themselves harboring an unusual investment. A mother who has entered deeply into sustaining a life cannot easily turn off the visceral connection, described so unempathically as a proverbial umbilical severing.

I have a million legitimate excuses for why I avoided writing this essay; I have never written so many reference letters, reviewed so many tenure files, and served on so many “important” committees (I will come back to this midlife challenge in a moment). But I have to admit that I procrastinated because living these middle years brings with it a close brush with finitude and loss. And who wants to focus on loss? I am not saying the sandwich years are unhappy. But as children grow and parents age, these years are a time of reckoning with end times—my own and my parents’. It startles me sometimes to think that my parents know daily their days are so numbered. The truism that you never know in departing whether you will see someone again presses upon us. And as I watch my children’s lives open up to a plethora of possibilities, I see my own closing down, my stamina declining, and new age-related ailments arising—like menopause, disrupted sleep, and an uncanny resistance to working so hard.

Women in mid-to-late career also face an unexpected but confounding accretion of responsibility, paired with a mounting awareness of one’s limited influence. Expanding responsibilities in the workplace flow into the vacuum left as children depart but bring less gratification. In pretenure years, I assumed life after tenure would be easier. Never did I anticipate that I would have multiple areas of scholarly expertise to cover (e.g., my old projects and my new projects), more students and junior colleagues to protect and promote, curriculums and disciplines to shape and secure, and academic societies to tend and oversee. The cumulative institutional and scholarly weight that needs lifting sometimes seems overwhelming. Each year the graduates who need reference letters in a sagging job market grows. One would think that power would accompany this expansion, but the ability to land someone a job, reverse a university tenure committee decision, counteract destructive faculty politics—all of this falls largely outside one’s influence, almost as in pretenure days; except now I feel more responsible than ever before.

One’s lack of influence is also acute within the family. A parent’s say over a child’s friends, teachers, and living situation diminishes as the years go by. And sustaining intimate relationships becomes harder. Last year, my husband and I didn’t see two of our sons for almost a year and have yet to meet their girlfriends and our third son spent a half-year in Australia. How does one stay in touch? Who does one visit when time and means arise—parents or children? And what is the extent of one’s accountability for their dental care, car maintenance, street savviness, financial solvency, and general well-being? In a word, deep bonds become harder to sustain, responsibilities become tougher to manage, and a strong undercurrent of loss pervades it all.

Even though these developments are distinct to midlife, viable responses are not much different from those of early adulthood. The maxim that one cannot “do it all” and so must be satisfied with mixed accomplishments just gets accentuated by aging bodies and abilities. So it’s important to keep invoking priorities and limitations at work and home. Just as I complained about meetings scheduled late in the day at work when I needed to be home for young children and, at the same time, protested at home the conventional cookie-baking ideal of motherhood and expected my kids to pitch in, so now I still have to set realistic expectations on both home and work fronts. I have worked to assuage parental guilt—writing about spirituality in families as not requiring one more item to do but rather a recognition of places where one has already established mundane practices that form faith (Miller-McLemore, In the Midst of Chaos). So now I still want to say go easy on self-critique. Build on what you already do well. Acknowledge loss and finitude. Welcome grace and forgiveness. One would think that all this should come more easily for religion scholars well-versed in longstanding traditions that have honed such ideas and created rituals to support them, but alas.

Equally important is the sustenance of support networks at home and work. Colleagues facing the same challenges have been essential to my own well-being. Before a regular academic conference, I met several times with two close women friends to share midlife challenges and discern our evolving calls. Hearing how they have dealt with aging and dying parents, wandering kids, and turning points in their careers gives me comfort and insight. Within our institutions, the responsibility of advocating for parent-friendly policies and educating colleagues about the value of family and domestic labor doesn’t end when our children leave home; nor does sharing domestic labor justly end at home (with partner, spouse, etc.). Perhaps most challenging, careful discernment and extra work are required to connect to children and parents not living in close proximity. It means cultivating availability; scheduling phone calls and visits; determining whether, when, and who to visit; and striving to strike a fine balance. This spring we chose a Gulf Coast rental with my parents over a trip west to see sons, knowing the years with healthy parents are short-lived even though a kid visit is long overdue.

Finally, even though I hesitate to say it in our “seek your own bliss” society, sometimes you just need to care for yourself. Today is Valentine’s Day. I didn’t send as much as a card to my sons and parents, even though in the past I’ve baked and shipped cookies and even gift cards (as one son reminded me in an e-mail today). I’m just looking forward to a quiet dinner at home with my husband, mourning and celebrating how quiet the dinner hour has become as our responsibilities have moved out into the world.

Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore is the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Professor of Pastoral Theology at Vanderbilt University’s divinity school and graduate department of religion. Recognized for her work on families, women, and children, a prominent leader in pastoral and practical theologies, and recipient of a Henry Luce III Fellow in Theology award, Miller-McLemore is author of numerous publications, including Also a Mother: Work and Family as Theological Dilemma (Abingdon Press, 1994), Let the Children Come: Reimagining Childhood from a Christian Perspective (Jossey-Bass, 2003), and In the Midst of Chaos: Care of Children as Spiritual Practice (Jossey-Bass, 2006).

Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore is the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Professor of Pastoral Theology at Vanderbilt University’s divinity school and graduate department of religion. Recognized for her work on families, women, and children, a prominent leader in pastoral and practical theologies, and recipient of a Henry Luce III Fellow in Theology award, Miller-McLemore is author of numerous publications, including Also a Mother: Work and Family as Theological Dilemma (Abingdon Press, 1994), Let the Children Come: Reimagining Childhood from a Christian Perspective (Jossey-Bass, 2003), and In the Midst of Chaos: Care of Children as Spiritual Practice (Jossey-Bass, 2006).

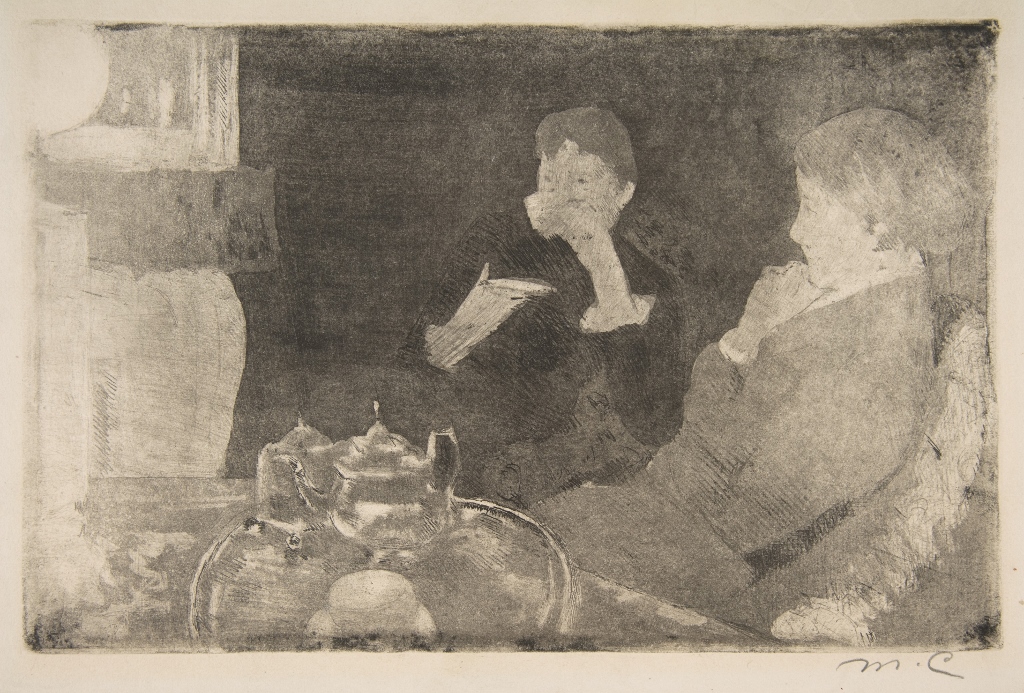

Image: "Lydia and Her Mother at Tea," Mary Cassatt, 1882. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Gustavus S. Wallace, 1932. www.metmuseum.org