Tolerance for Others and Same-Sex Marriage

We live in an era in which public opinion and political positions are sharply divided. This has been exemplified both by the ineffectiveness of Congress in recent years and by the sharpness of the 2016 presidential campaign. One of the most controversial political and moral issues of our time has been whether couples of the same sex should be allowed to get married. In its fundamental sense, that problem was settled by the Supreme Court’s 2015 creation of a constitutional right to such marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges1, but that hardly has resolved everything. Even if one assumes, as I do, that an overturning of that decision is highly unlikely, it does not settle how individuals and companies must treat married couples of the same gender. Recent proposals for broad exemptions within states have generated intense controversy, and we can expect Congress to face this issue once the new president and members of Congress are in office.

We badly need a higher degree of respect and tolerance for the views of others, including their religious convictions and their fundamental beliefs about equality. If we managed to achieve that, we should be able to work out a principled and practically viable compromise between the opposing perspectives. Before suggesting that, I sketch the legal setting, and the competing views about same-sex marriage.2

The Legal Setting

What confuses some about the present legal circumstance is the relation between constitutional rights and possible exemptions from what people are required to do. Constitutional rights in the United States concern what the government may not do. Government offices, for example, cannot refuse to marry gay couples. But private individuals and organizations can operate in ways denied to the government unless an antidiscrimination statute bars such choices. State statutes typically forbid such discrimination based on race, gender, and religious connection. A number of states now have such provisions that forbid discrimination against homosexuals, but most still do not. Typical antidiscrimination statutes provide certain exemptions. The key issue for our time is whether such statutes should reach homosexual behavior and same-sex marriage, and, if so, what range of exemptions from equal treatment is appropriate.

Sharply Different Perceptions

The fundamental understanding that marriage is essentially between men and women is fairly simple to grasp in light of history. The concept of marriage has been closely connected to family life and the raising of children. For nearly all of human existence, the only way to create children was by sexual intercourse between men and women. Marriage between the two physical parents helped to assure stability and child support in family life. Although it has been suggested that this theory is undercut by the absence of any need for couples to produce evidence of their reproductive viability prior to marriage, that critique is misguided, given that a couple’s ability in this respect could not be factually determined, and few people were living to an age in life when procreation definitely would not occur. No doubt, the fact that the overwhelming proportion of people were sexually attracted to those of the opposite gender strengthened the approach of limiting marriage to men and women.

How does religion play in all this? Biblical texts suggest that marriage is between men and women, and that sexual relations between those of the same gender are misguided. For a person who believes that God created this world and that the texts reflect God’s will, the passages are hardly surprising since they fit with the fundamental physical characteristics of most human beings. A person who rejects religion in general, or any assumption that specific biblical passages necessarily reflect God’s will, will find this conviction to be without intrinsic force. But even she should not be surprised, given the long-standing dominance of Christianity in this country, that a large number of fellow citizens still subscribe to that position.

How do same-sex couples and the proponents of gay marriage see things? For a long time, the Christian tradition and the laws of this country rejected all homosexual involvement. A very high percentage of people have a strong inclination to sexual interactions, which often lead to loving relationships that are among the richest of human experiences. Although a substantial majority of people are mainly attracted to those of the opposite sex, some are drawn to those who share their gender. To expect, or ask, that these people to simply refrain from sexual involvement for their entire lives is extremely harsh. Yet for most of our history, these interactions were actually criminal, and other forms of discrimination against known homosexuals were very common. In modern times, the criminal laws were rarely enforced, and the Supreme Court finally declared them unconstitutional, but gay people understandably regard themselves as having been for a long time victims of unjust discrimination.

Since we no longer need heterosexual sex to create children and many children now are raised by single parents and same-sex couples, did it make sense to preclude gay couples from getting married? After a number of state legislatures and lower courts had created a right to same-sex marriage, the Supreme Court, by a 5–4 margin, declared that the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed it. Justice Kennedy’s opinion emphasized the basic rights that underlie marriage, and the absence of any solid reason to deny those rights to same-sex couples. Among other things, the ability to marry will counter an unfair form of unequal treatment. Whatever one thinks about the constitutional conclusion here, the fundamental arguments for allowing these couples to marry are decidedly strong.

Tolerance and Mutual Respect

This brings us to the need for tolerance and mutual respect. Let us start with the traditional religious believer who perceives that marriage in God’s eyes is between men and women. Two points are crucial here. The first is that secular law in a liberal democracy should not be expected to enforce what are seen as religiously grounded moral truths. As a crucial example, many people who believe abortions are morally wrong, including the former Roman Catholic governor of New York, Mario Cuomo, also think it makes sense not to have the criminal law prohibit them. And many who suppose that some divorces are inappropriate and immoral do not wish the civil law to enforce that view.

A second key consideration is that any believer needs to understand why it is that many in the population, including an increasing number of the religious population, do not share his views about same-sex marriage. If one thinks seriously about human capacities and inclinations, one cannot avoid understanding why few homosexuals feel comfortable about avoiding all sexual relations, and why, if these are legal and frequently engaged in, extending a right to legal marriage has a very solid foundation. Even if a person believes that on genuine religious grounds, marriage in God’s eyes must be between men and women, he has powerful reasons both to understand why others see things differently and why such a recognition in secular law is not necessarily bad.

For gay people and other strong supporters of same-sex marriage, a similar perception is needed. Given the long Christian tradition and its great importance in this country, those who strongly believe in same-sex marriage need to recognize that it is not surprising that a fairly large percentage of the population still believes genuine marriage must be between men and women, and that this view is not necessarily an outright negative opinion about homosexuals and how they should be treated. More particularly, people must understand that “tolerance” for others includes not demanding that they act directly at odds with their deep convictions, unless a powerful reason requires that compulsion.

What Makes Sense

Where does this leave us for what makes sense for legislators and others within our liberal democracy? We definitely need genuine mutual recognition. The religious objectors need to understand that some people have strong homosexual inclinations, that almost all of those people will wish to have sexual relationships, that they, like the rest of us, will welcome enduring relationships, and that they believe they are entitled to equal treatment, which includes a right to get married and to be recognized as so by others. On the other side, those who strongly favor same-sex marriage need to perceive why marriage has traditionally been between men and women, and why in a country with a deep Christian religious tradition, many Roman Catholic and evangelical Protestants, as well as members of other faiths, such as Orthodox Jews, do not consider same-sex marriage to accord with God’s will. A person needs to recognize this even if he sees all religion or particular forms of religion as deeply misguided.

What these understandings tell us is that we have a division of convictions that cannot be simply disposed of. We face genuine competing interests that require degrees of sacrifice. On reflection, insisting that one side or the other submit to a total sacrifice is unjust and does not make sense. I believe the most appropriate approach is to distinguish actual participation from subsequent treatment.

The fundamental relevance of this line can be shown through a bit of reflection on personal matters and on how most organizations treat people. Most adult Americans provide services of a wide variety to other people. Almost none of us, and I include teachers and professors, refuse to help those whose moral views and lifestyles differ from our own. Yet if we were asked to directly participate in an action we considered deeply immoral, we would almost certainly say “no.”

When we turn to organizations, such as restaurants and hotels, they do not engage into a serious inquiry about people’s lives. Is same-sex marriage special here? The religious leaders of some of those enterprises may believe abortions are immoral, that married people should not commit adultery, that sexual relationships outside of marriage are sinful, or that not every civil divorce meets necessary religious standards. Yet we are unaware of frequent refusals of service because an individual or couple has violated these standards or of serious inquiries into the backgrounds or relationships of those who seek services. Given this social reality, it is hard to understand a principled basis why such an organization should be able to refuse services to same-sex married couples that it is providing for people who have been engaging in what its leaders consider other serious wrongs.

Where this should leave us is not too hard to understand. People with convictions that same-sex marriage is not a genuine marriage in some fundamental sense should not be required to participate in one, but neither organizations nor individuals should have a right to refuse ordinary services to same-sex married couples. To take an analogy, this is essentially what the federal laws provide regarding abortions. Doctors and nurses need not perform them or assist their performance, but they have no right to refuse a woman other treatment because she once had an abortion.

The edges of what should count as participation are not themselves obvious, but to take two actual cases, I believe that being the primary photographer at a wedding, taking hundreds of photographs some of which will last for decades or longer, should count as participation, but that baking a cake for a wedding celebration should not. So long as the marriage is legally recognized, treating the couple as married for insurance purposes should not count as participation. A harder question I will not explore here is what should be allowed for institutions putting children up for adoption.

What I have urged about what practically should be done rests on two related assumptions that will not be widely accepted in every location. The first is that antidiscrimination laws should generally forbid unequal treatment for homosexuals and for same-sex married couples. The second is that accommodating exemptions should be grounded in what is fairest. I have not addressed what should be done in terms of political necessity if much broader exemptions are needed to assure passage of an antidiscrimination provision. That will vary among different states and locations. But whatever may be true about that, it is still crucial that both sides recognize that we have genuine competing considerations, that we need mutual understanding and tolerance, and that direct participation is not the same as affording subsequent equal treatment. If we could achieve a higher degree of tolerant understanding than we have now, the issue of exemptions could become less divisive culturally and politically.

Notes

1 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015).

2 My fuller perspectives on this topic are in the recently published Exemptions: Necessary, Justified, or Misguided (Harvard University Press, 2016).

Kent Greenawalt is a university professor at Columbia Law School where he specializes in the areas of constitutional law and jurisprudence with an emphasis on church and state, free speech, legal interpretation, and criminal responsibility. He is the author of many books, including Conflicts of Law and Morality (Oxford University Press, 1987); Religious Convictions and Political Choice (1988); Private Consciences and Public Reasons (1995); and Does God Belong in Public Schools? (Princeton University Press, 2005).

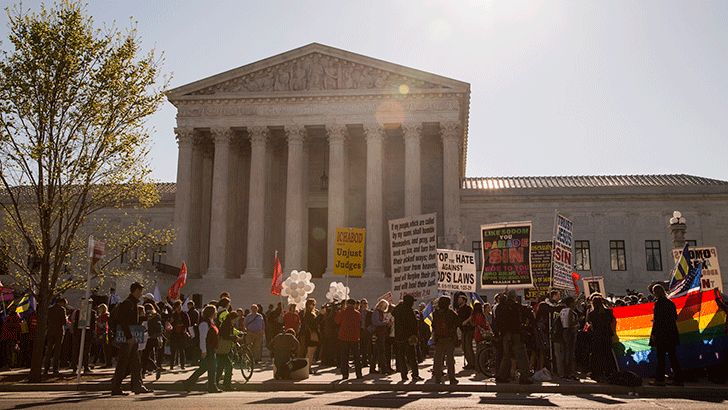

Photo Credit: "Supreme Court, Tuesday morning" (CC BY-SA 2.0) by Lorie Shaull

Religious Studies News welcomes comments from AAR members, and you may leave a comment below by logging in with your AAR Member ID and password. Editors review all comments and reserve the right to not post any comment they deem offensive, inappropriate, defamatory, or simply irrelevant. Accepted comments will usually post within 1 to 3 business days. Comments reflect the views of the author and are not indicative of approval or endorsement by RSN or the AAR.

- Log in to post comments

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version