Engagement with the Digital, Department Life, and Professionalization

This article is the third in a series that unpacks and contextualizes data on religion departments collected by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Humanities Indicators project. All three articles were written in collaboration between the American Academy and the AAR. Various data sources are noted along with numerous links to reports and indicators maintained by the Indicators. The first article in this series explored trends related to undergraduate and graduate enrollments and degree completions; the second article focused on indicators related to graduate students and faculty as well as those pertaining to working conditions.

The recent Humanities Departmental Survey (HDS) offers a rich set of data on vital structural aspects of religion departments, such as engagement with digital skills in the curriculum, use of online education (before the pandemic), and support for student careers. One particular value of these data comes from the ability to compare religious studies to other humanities fields. Taken together, these data present a number of strategic avenues for action in religious studies, especially in light of the growing demand for digital skills and teaching experience.

Digital Humanities

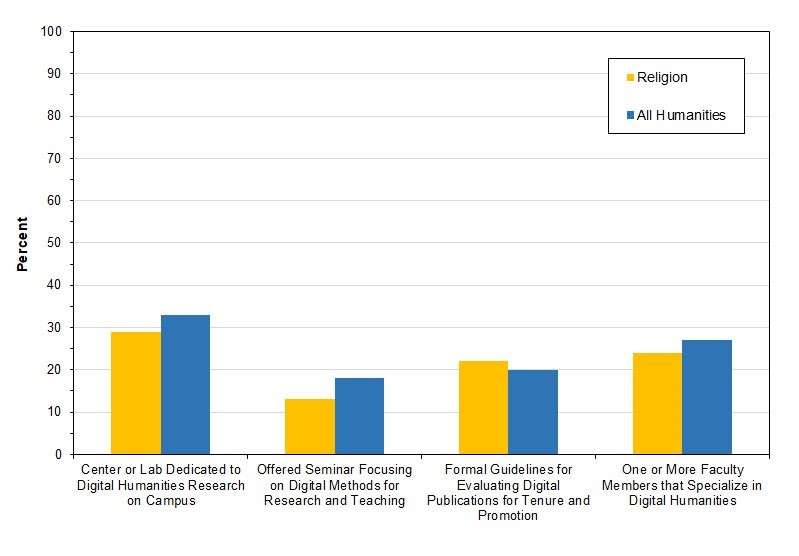

Perhaps most notably, religion departments appear modestly less likely to engage with digital tools than their peers in other humanities departments. The Humanities Indicators measured engagement with digital humanities through four measures: the presence of a dedicated center or lab on campus, specialized faculty in the department, relevant course offerings, and departmental guidelines for the evaluation of digital scholarship (see Fig. 1). Among these, religion departments reported higher rates than the average across all humanities on only one question: the provision of guidelines for evaluating digital scholarship. That finding may be a result of work done by AAR members and staff to develop and share the Guidelines for Evaluating Digital Scholarship. Such an example would underscore the importance of such actions on behalf of professional associations to raise awareness of and set standards for emergent issues.

Fig. 1: Share of Departments Engaged with Digital Methods, Fall 2017

Source: Humanities Indicators, The State of Religion Departments in Four-Year Colleges and Universities (2020), tables REL21 and REL19.

For each of the other measures, however, religion departments were less likely than other humanities disciplines to be engaged with these activities. An estimated 24% of religion departments had one or more faculty members specializing in the digital humanities, compared to an average of 27% among all humanities departments. And only 13% of religion departments offered a seminar on digital methods for research and teaching; the average across all departments was 18%.

Interestingly, engagement with digital work varies widely by institutional sector. For example, across all disciplines, each measure of engagement with the digital was at its highest at research universities, and the largest gap related to digital humanities centers and labs. The same was true of religion departments, where digital humanities expertise, resources, and courses were most likely to be found at research universities. (Table 21 HDS-3).

Distance Education

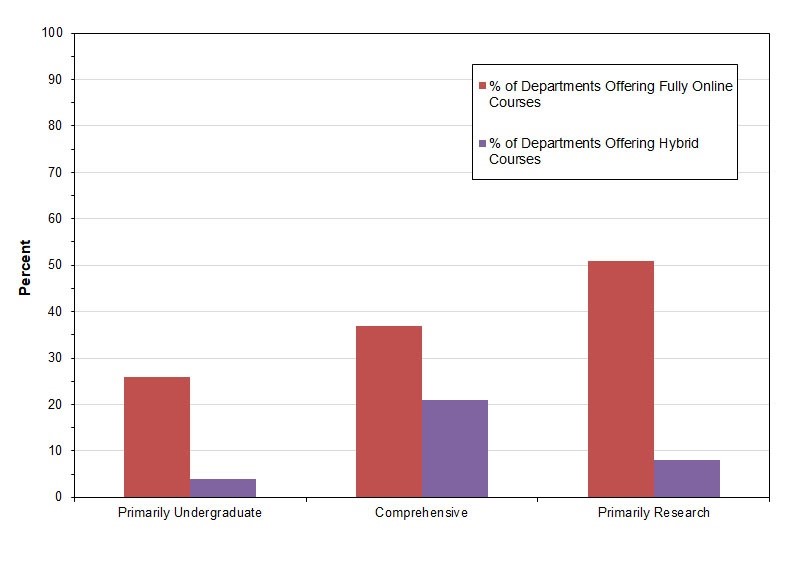

While the coronavirus pandemic has had many impacts on higher education, one of the most notable has to be the sudden shift to fully online and hybrid modes of education. The department survey (which was conducted in 2019, but asked departments to look back at the 2016–17 academic year), reveals just how much the pandemic disrupted normal practices in most religion departments.

Just 22% of religion departments offered fully online courses that year (compared to 30% across all humanities departments). A smaller share (15%) of religion departments offered hybrid courses, which was equal to the rate reported across the humanities. From this, we learn that most religion departments were not offering online or hybrid courses before the pandemic.

Fig. 2: Share of Religion Departments Teaching Online or Hybrid Courses, 2016–17 Academic Year

Source: Humanities Indicators, The State of Religion Departments in Four-Year Colleges and Universities (2020), table REL18.

Among religion departments that offered such courses, there were an average of 4 fully online courses, and 8.4 hybrid courses offered. Interestingly, both of the figures are nearly double that of the humanities as a whole--indicating that while considerably fewer departments had online courses, those that did were prolific.

Similar to other humanities departments, religious studies departments at primarily research institutions were nearly twice as likely to offer online courses as those at primarily undergraduate institutions. Across all disciplines, departments at public institutions were twice as likely to offer both fully online, and hybrid courses (Table 20 HDS-3). The gap is not as pronounced among religion departments but a wide gulf remains.

Career Services and Professionalization

Given the ongoing debates about the value of humanities skills in the contemporary job market, career services and preparation of students for jobs after college is another key area of interest. Data collected by the American Academy offers an important perspective for these discussions, as they offer some insight into the support available at the departmental and institutional level, and help to situate religion among its peer disciplines.

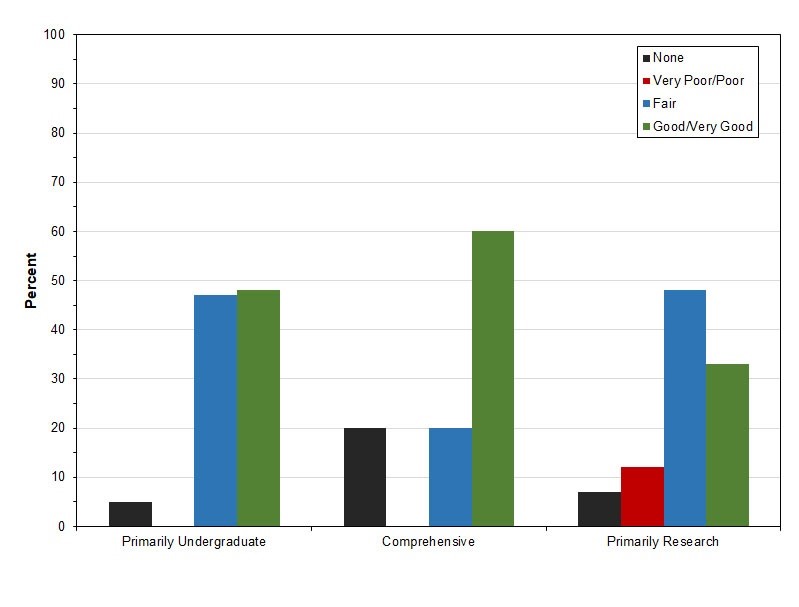

For instance, 48% of religion departments rate career services at their college or university “good” or “very good” for their students. While just 2% rated the programs “poor” or “very poor,” 9% did not think they even existed on their campus. The rest rated their programs as merely adequate (Table REL21 HDS-3).

Similar to other humanities departments, religious studies programs at research universities seemed the most critical of their career services programs, with barely a third of departments rating them as good or very good, and one in five judging them poor or not available (Table 27 HDS-3).

Fig. 3: Religion Department Ratings of the Quality of the Student Career Services Offered at their Institutions, by Carnegie Type

Source: Humanities Indicators, The State of Religion Departments in Four-Year Colleges and Universities (2020), table REL21.

Most—but not all—religion departments try to fill in some of the career gaps for their students. For instance, 52% of them either offered or required career-oriented coursework or workshops for their students (though this was considerably less than the average of 75% among all humanities departments).

The disparity was quite different when it came to doctoral students. Among all humanities disciplines, 68% of doctoral programs were either offering or requiring occupationally-oriented courses or workshops for their PhD students, but 70% of religion departments did so (Tables 23 & 25 HDS-3). Religion departments were substantially less likely to offer internships to their doctoral students, however, as 42% of humanities departments did so, compared to just 11% of religion departments.

Beyond the provision of opportunities for students, the Humanities Departmental Survey also assessed other ways that programs support professionalization. Humanities programs are increasingly scrutinized along these lines, making such data quite useful to program leaders in their advocacy for the continued importance of religion departments on campus. One of the ways that humanities departments are perceived to make contributions to professionalization is through interdisciplinary teaching arrangements. On that score, a relatively large percentage of religion departments had faculty teaching courses in a professional school (e.g., law school, business school, engineering, or medical/dental/nursing school) at their college, with approximately 17% of religion departments reporting that kind of arrangement compared to an average of 12% in all humanities departments.

Career Outcomes

One of the other critical ways that humanities departments engage with the topic of professionalization is through the collection of career outcomes for students. Such outcomes are an increasingly common component of new program proposals and reviews, and their absence can be used to justify proposed program cuts. In light of these growing demands, humanities advocates are marshaling data and resources to aid departments in their response. These broad resources are especially important in light of the disparate access to resources to sustain data collection at the departmental level.

The American Academy’s survey asked specifically about collection of career outcomes for graduate students—in most cases assumed to be a lesser burden than collecting such data for undergraduate students. Across all humanities departments, only 40% track career outcomes for their graduate students, and 29% reported tracking no career outcomes at all. Religion departments were even less likely to track career outcomes for their students, as 44% of departments fail to track any information about their students’ outcomes. This was the second highest share in the humanities.

Religion programs at doctorate institutions were 10% more likely to report tracking career outcomes, a disparity likely driven by the need for additional resources for that effort (Table REL11 HDS-3). These data point to likely challenges for religion programs as such outcomes are becoming an increasingly common aspect of program review.

As religion departments struggle to meet the current moment, the HDS provides a critical snapshots of department efforts relative to other other humanities disciplines. The data offer a baseline for thinking about your own programs, and offer potential evidence of peer models for success.