In one of my classes, I have a practice that I call “Two-Minute Reflections on Last Class” as a means of letting conversations from one class session leak into our conversations in the next. Here’s one that captures a bit of the essence of this tricky reality of work/home (im)balance:

Paying bills for a family of four on a single income,

keeping people fed, clean, warm and well,

raising little human beings, new to the world,

to be loved, to love, to be responsible, thoughtful, kind and attentive,

providing a sense of home, a ground underneath our feet

1,300 miles away from our closest family—

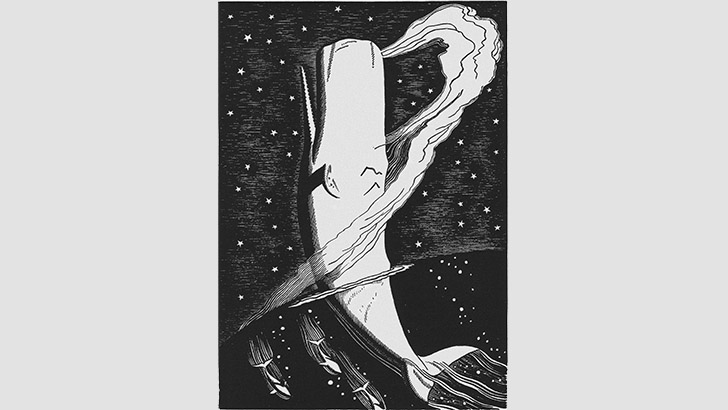

this is exhausting.

Daily log:

7:01 am—hit snooze (and again, and sometimes again)

7:30ish: get up and get dressed.

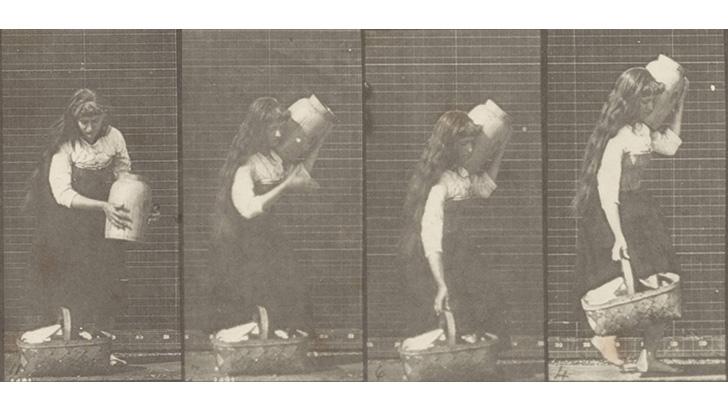

7:45ish: get baby up for a diaper change and morning feeding

8:10ish: get three year old up and fed, pump excess to maintain adequate milk supply

The Guide for the Guild is a series of blogs posts submitted by AAR members in response to the Status on Women in the Profession Committee's work-life balance project. To learn more, visit SWP's page on the AAR website.

The Guide for the Guild is a series of blogs posts submitted by AAR members in response to the Status on Women in the Profession Committee's work-life balance project. To learn more, visit SWP's page on the AAR website.