A Theory and Method of Comparison - Part 1

This is Part 1 of "A Theory of Method and Comparison." Below, Georgia State University associate professor of religious studies, Molly Bassett, writes about a dual-level course she's teaching for a third time this fall titled "Religious Dimensions in Human Experience." Part 2, to be published September 16, is a reflection by one of her former graduate students, Sarah Levine, who took the course the first time Bassett taught it in the fall of 2010.

Late last spring, Sarah Levine, a former student now senior editor for Religious Studies News, emailed me to ask if I would be interested in writing for the newsletter’s new column “Theoretically Speaking.” Her e-mail came at a perfect time: I had just begun redesigning one of the courses Sarah took with me several years ago. In fact, she took the first version of the course, and it is now in its third iteration. Sarah and I met over coffee, and I proposed that she write with me. She graciously agreed. Our essays reflect on “Religious Dimensions in Human Experience,” a dual-level (graduate and undergraduate) course that uses a comparative method to explore “religion” and religions as anthropological projects.

Sarah took a version of the course inspired by an epigraph and op-ed.1 We examined themes like certitude (or ignorance, as Sarah puts it) using Errol Morris’s Times essays, and Oliver Sacks, Daniel Dennett, and Gloria Anzaldúa informed our conversations about storytelling and “the self.” This fall, the course will look completely different, but the underlying method, which I describe below, is the same. While reading widely for my research, I came across Wendy Doniger’s observation, “Animals and gods are two closely related communities poised like guardians on either threshold of our human community, two others by which we define ourselves” (1989, 3). My aim in “Religious Dimensions” is always to provide space and structures for students to ask some of the big questions that bring them to the study of religions. This fall, we will be examining humans as beings that stand “Between Animals and Gods.” In this essay and the one that follows it, Sarah and I explain a bit about the place and application of theory and method in the course, and Sarah her experience of the course.

The Ensemble Approach

The comparative method I use is one that I learned from Davíd Carrasco. In his Religions of Mesoamerica, Carrasco describes the “ensemble approach” as a way to piece together a picture of cultures disrupted by Contact and colonialism. In his own writing on Mesoamerica, Carrasco draws on a variety of sources, including archaeological records, ethnohistoric texts, pictorial manuscripts, and ethnographic accounts (2014: 26-37). He uses a similar approach when he organizes projects for the Moses Mesoamerican Archive, a scholarly collective that co-authors studies like Cave, City, and Eagle's Nest: An Interpretive Journey through the Mapa de Cuauhtinchan No. 2. In this course, I borrow Carrasco’s approach (and his title, with permission).

In “Religious Dimensions,” I combine an ensemble approach with a comparative one so that students consider a topic or sequence of topics through a series of readings, images, sites, and sounds that do not—at least at first glance—look like they go together. I also use an ensemble approach to assemble the course materials: I ask other area experts for advice, I invite guest speakers to present in class, and I assign a variety of media. This fall, our ensemble will include two new aspects: field trips and (potentially) you. We will venture outside the classroom to learn from ZooAtlanta research scientists and art historians at Emory University’s Michael C. Carlos Museum. Students in the course will be writing and creating podcasts, audio ensembles that collect and curate specific course themes that will be posted on our course webpage. The ensemble runs throughout.

“Religious Dimensions in Human Experience: Between Animals and Gods”

Introductions and conclusions bookend the course’s three foci: (1) our primary animal, the snake, as presented by Western science; (2) the snake as a subject of natural histories in India and Mesoamerica; and (3) snakes as deities and divine symbols in Hindu and Nahua religions. First, we will learn about the scientific side of snakes. Questions like, “What is a reptile?” and “What is a snake?” introduce students to concepts like taxonomy and Evo-Devo, while giving them a baseline understanding of the animal’s biology. Readings about the Eastern Indigo, a recovering species in the Southeast, underscore snakes’ local relevance. A third of the way into the course, students will have a good sense of the snake—one reinforced by a field trip to visit ZooAtlanta’s herpetologists and “meet the snakes.” The second and third units, snakes as presented in Indian and Mesoamerican natural histories and religions, will complicate the first.

Image plate depicting examples of the Ophidia clade in the Western taxonomic system. From Natural History of the Animal Kingdom for the Use of Young People (1889) by W. F. Kirby. via Archive.org.

Image plate depicting examples of the Ophidia clade in the Western taxonomic system. From Natural History of the Animal Kingdom for the Use of Young People (1889) by W. F. Kirby. via Archive.org.The course’s comparative turn hinges on one becoming many. Students know the snake as order Squamata, suborder Serpentes—that is, as a scientifically classified biological creature—and then they see the snake named and described differently in other cultural systems. This shift draws on natural histories and folkbiology, the study of how other peoples—particularly indigenous peoples—study plants and animals. Editors of Folkbiology Douglas L. Medin and Scott Atran argue that “people’s actions on the natural world are surely conditioned in part by their ways of knowing and modeling it” (1999, 1). If this is true (and I think it is), then how my students know and model the world directly affects how they are in the world. An ensemble approach exposes students to multiple models, and so their “actions on”—perhaps better, actions in—the (natural) world are complicated and less restricted. This notion—that by highlighting similarities and differences, comparisons illustrate the ensemble’s multiplicity—brings us back to the course’s learning objectives: that knowing the world deeply—through careful reading, writing, and analysis—affects how people act in and on the world.

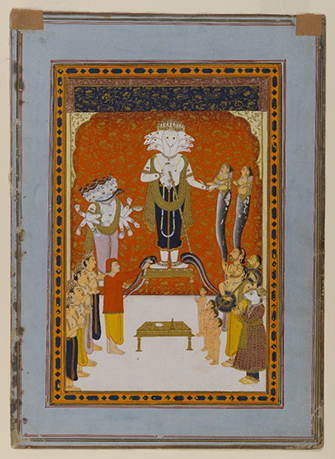

"Devotions to Nagadevata" (c.1790, India). via the Brooklyn Museum

"Devotions to Nagadevata" (c.1790, India). via the Brooklyn MuseumThe Ensemble as Action

In her recent book The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, Elizabeth Kolbert takes readers inside a series of specific events occurring at particular places to explain how we have brought about the Anthropocene. The course starts with Kolbert’s work, which brings a sense of urgency to the class and functions as a model for the students. She, too, gathers materials from diverse fields and draws on a variety of colleagues’ expertise to craft well grounded arguments. In small groups, my students will research, write, and produce podcasts that integrate material from diverse disciplines. Their podcasts will take listeners, including their classmates, down tangents and through new territory as they trace their own interests in “Between Animals and Gods.” In their final reflections, they will compose essays like these that interweave assigned materials and their own podcasts through a reflection on the course. These tasks require them to read for comprehension and employ comparisons to understand how different people(s) see animals and gods and themselves in relation to the two.

Part of the work of humanities classes and scholars is teaching students how to evaluate information, especially given how easily accessible information is. Students in this course test the theory that humans see the world comparatively—paraphrasing Doniger, that we locate ourselves by drawing comparisons. Hopefully, they will come to know the world a bit differently and be in it a bit differently as a result.

Notes

1 ^ The epigraph from Javier Marías’ A Heart So White (1995) appears in Rabih Alamadinne’s The Hakawati (2008): “Everything can be told. It’s just a matter of starting, one word follows another.”

References

Atran, Scott and Douglas Medin, editors. 1999. Folkbiology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Carrassco, David. 2014. Religions of Mesoamerica, 2nd edition. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Carrassco, David and Scott Sessions, editors. 2007. Cave, City, and Eagle's Nest: An Interpretive Journey through the Mapa de Cuauhtinchan No. 2. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Doniger, Wendy. 1989. "The Four Worlds." In Animals in Four Worlds: Sculptures from India, by Stella Snead, 3–24. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. 2014. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

Molly Bassett lives in Atlanta with her husband Mike, daughter Jennings, and two dogs, Chance and Owen. Everyone in the family enjoys running and walks. When she’s not reading Eric Carle and Dr. Seuss, Molly works as an Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of Religious Studies at Georgia State University. She recently published The Fate of Earthly Things (Texas, 2015), a study of Nahua (indigenous Mexican) concepts of deity and deity embodiment, and her next project explores how Nahuas describe relationships between natural and supernatural things and persons. Her research appears in History of Religions, Material Religions, and Teaching Theology and Religion. She’s blogging about her fall course for the Wabash Center, and she keeps track of her work life here.

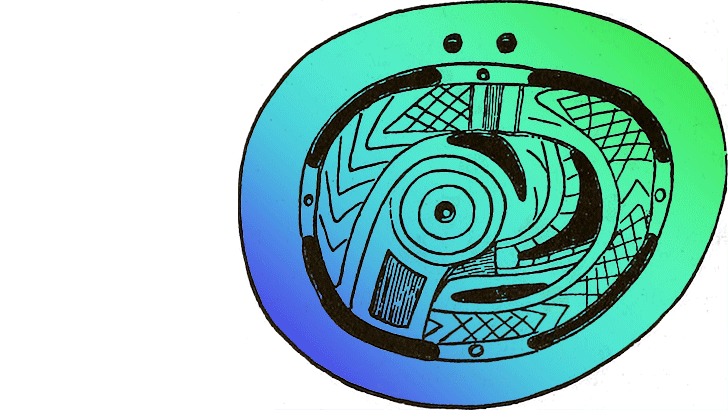

Image: Unmodified image appeared in the paper "Art in Shells" by William H. Holmes, published in the Transactions of the Anthropological Society of Washington, Volume II (1882). Holmes identifies the image as the "common yellow rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) of the Atlantic slope." Via Archive.org.