Normativity in the Study of Religion: A Dialogue about Theology and Religious Studies

Introduction by Thomas A. Tweed

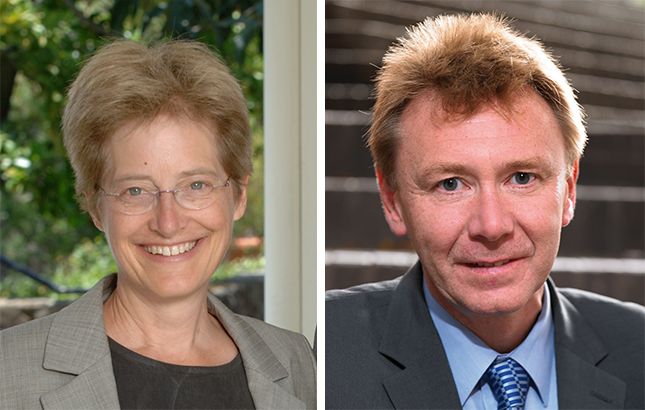

Academic fields are constituted by their debates, and the relation between theological and religious studies approaches has been one of the most enduring but least productive debates in the study of religion. This dialogue between Graham Ward, a distinguished theologian, and Ann Taves, a distinguished religious studies scholar, attempts to refine that conversation. It is the product of months of exchanges as they read each other’s work (Taves 2016; Ward 2014) and tried to discern where they concurred and where they diverged as they prepared for a plenary session, “Normativity in the Academic Study of Religion,” at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Religion. That conference session, and this published version of their scripted dialogue, strives to reframe the conversation about theology and religious studies.

I organized the session because I thought it might help to talk more precisely about what unites and divides scholars as we imagine the nature and scope of the academic study of religion—a topic I also addressed in my 2015 AAR presidential address (Tweed 2016). I was concerned, on the one hand, that some theologians seemed surprisingly disinterested in religious studies scholarship, including historical or social scientific studies and analyses of their own tradition, even though every theologian I know engages scholarship in some other discipline. Some theologians even seem a bit defensive, complaining that the academy doesn’t respect their discipline, yet they don’t engage the research of those they want to persuade. On the other hand, I was concerned that some religious studies scholars not only didn’t engage those doing constructive religious reflection, or arrogantly dismissed them, but they also claimed that the AAR’s “big tent” had grown too large and that those who enact values and make normative judgments have no place in it.

Despite all their talk about positionality, some religious studies scholars seemed to ignore the ways that they too affirm values and make judgments. In short, it seemed to me that we either weren’t talking to each other, or that we were talking past each other. So more talk seemed like a good idea, for it is only those unwilling to talk—and deeply listen—who are unwelcome in the AAR’s big tent. To be a participant in the academic study of religion, it seems to me, means opening your views to continuing scrutiny and giving reasons for your claims, even if that means explaining where you think reasons come to an end.

But who should do the talking and what should we talk about? It did not seem helpful to conjoin the shrillest voices from the extremes of the continuum on this issue, though that might have yielded an entertaining spectacle. Rather, I decided that a dialogue between two judicious scholars with some overlapping interests (about neuroscience and beliefs about anomalous experiences) and with some similar experiences in navigating theological as well as religious studies settings might be most helpful. I thought this sort of exchange promised to generate more light than heat. I hope you will agree that my hunch was right.

To help you interpret the exchange that follows you might want to know how it began and proceeded. I suspected that it might help if the participants talked about their deepest values, the commitments that guide their work and provided the language they use when they make normative judgments about how scholars ought to think and act. So I asked each dialogue partner to identify the most central epistemic, moral, or aesthetic values that inform their work. I asked them to then cordially but frankly explore what they share and what they don’t. I hoped that, in the end, this strategy might yield some hints about how we might reframe the conversation, or at least identify some possible next steps to further clarify converging and diverging commitments.

To my delight, these conversation partners went even farther than I originally had hoped. They communicated for several months, exchanging drafts and offering comments. So what you see below is a scripted dialogue, one that has been revised in and through ongoing conversation. The result of that collaboration is divided into several sections. First, they position themselves and talk about their institutional contexts and the tensions that arise as they try to enact their ideals. Second, they disclose their bedrock values and explore how they diverge. Finally, they consider disciplinarity and the relation between theology and religious studies, imagining the implications of all this talk for reframing our understanding of what divides and unites us.

Positioning: Privilege and the Tension between Context and Ideal

Taves: In reflecting on how we position ourselves intellectually and academically in our institutional and national contexts, we realized several things. First, we are both in relatively secure, privileged academic positions, which in both cases are congruent with our values and sense of vocation, and we recognize that many others, whether colleagues or graduate students, are not in that position. So we want to acknowledge at the outset that we realize that where we’re positioned gives us a freedom to pursue research in ways that many do not have.

Ward: Second, in the course of our conversation, we also realized that despite the differences in our institutional contexts and sense of vocation, we share a common commitment to the formation of students prepared for citizenship in a world in which religion plays a vibrant and challenging role. Our conversation allowed us to surface the differences in the way we are seeking to advance this fundamental value in our respective contexts.

Values: Integrity versus Methodological Agility

Taves: We began to clarify these differences by talking about values that are central to us in our teaching: integrity and methodological agility.

Ward: In thinking about teaching, I identified integrity as one of my central values. Integrity is about telling it as it is, not as you would like it to be or you believe your doctrine teaches or your home church tells you your doctrine teaches. The study of theology can’t be compartmentalized. It’s about life, damage, power, violence, and healing. It has to be governed by a notion of wholeness. I see integrity as a moral virtue formed by living, learning, and reflecting upon what we believe and what life shows us. That “wholeness” is not something we grasp as such. We are always on the way to it as circumstances change.

Why this is important theologically? Because there are multiple legitimation processes and authority structures in the institutions that theology fosters: doctrines with anathemas attached; internal disciplinary bodies with respect to those teachings, creeds, confessions, and sacred texts; appeals to revelation. Integrity seeks alignments here between official teaching and one’s lived experience of what is shared and recognized to be the case with other people (religious or nonreligious). This calls for critical and hermeneutical engagements with what is received through these legitimating powers and authority structures.

I can think here of two concrete examples. First, when I was teaching for the summer in a Bible school in Nigeria. The team I went with from Britain included a number of women. When we all got there the women were not allowed to teach because of a scriptural injunction. We had to work among ourselves and then with the others in the Bible school to come to an understanding of that biblical injunction in a way that enabled the women to be taken seriously as coteachers. In the end we failed; and the women were divided. Some teamed up with a man they knew would encourage their resistance in any class taught; some accepted the male headship line and worked with pastors’ wives. The second example comes from encountering Christian groups that cannot accept gay relationships as wholesome, authentic, and God-given. Again a negotiation, not always very successful, takes place because the integrity of personal and collective experience of being gay as being as much a divine gift as being straight is resisted. Sometimes this means people have to leave certain groups with a particular theological position because the resistance is so intense that spiritual and somatic well-being is at stake. In my own theological writing, I am always sensitive to the power involved in speaking about God. A confession of limits and fallibility is important for allowing spaces for contestation and correction.

Taves: I understand your concerns, but ironically I began articulating a different value as I taught graduate classes that included both students preparing for the ministry and students preparing for academic careers in the humanities–a value that you might view as promoting compartmentalization. In Claremont, I thought of it as learning to speak in different voices or from different subject positions, and specifically, in that context, learning to identify and switch between insider and outsider positions relative to a tradition or an academic discipline. In my more recent work, I’ve referred to this as methodological agility and extended it to include the ability to shift back and forth between humanistic and scientific presuppositions. Methodological agility, as I’m conceiving it, has the value of encouraging us to explore what experiences, beliefs, and practices are like for those we study and those we teach. This would include religious and nonreligious students exploring what various religious and secular points of view are like. From a scientific perspective, it allows us to compare people’s beliefs, practices, and experiences, along with our own, and offer explanations for human behaviors that may differ from those offered by those we are studying.

So I’m curious to know what you think. Does it sound to you like cultivating the ability to adopt more than one point of view is just another form of compartmentalization that undermines integrity and wholeness?

Ward: Methodological agility, if I understand you, is not primarily a moral pursuit, though if linked to entering into the standpoint of another it can become one. I’m sure from your description it’s not just a functional procedure that erases personal investments of interest. Crossing disciplinary borders for me is part of an ongoing “negotiation” that has integrity or a greater wholeness as its goal. The desire to understand across the borders would run counter to compartmentalization. The compartmentalism I’m thinking of is where the dictates of a particular position refuse to encounter the dictates of another position, believing that “we have the truth.” I think your approach could help that top evolutionary biologist who accepts mutation is random and adaption turns on the throw of blind dice and also is a Christian believer in God as a loving creator. Scientific method uncovers the world in a certain way and is ringed with caveats and what remains unknown. I’m not sure your methodological agility can handle power structures and institutionalized legitimation processes, the forces that want people to believe what they believe because unity and belonging is based on that. I’m not sure your commitment to methodological agility can handle or disrupt processes that can lead to radicalization. So I suppose I would ask you about the goal of methodological agility. Is it to hold and maintain multiple standpoints? What about the institutions entrenching their standpoint as the right one, demanding allegiance above all others? Does your methodological agility treat ideological socializing structures–even within academic disciplines?

Taves: I understand methodological agility as an ability to distinguish between the different types of aims and distinct kinds of evidence we bring to different forms of inquiry. So to take your Christian evolutionary biologist as an example, I would want to distinguish between the conclusions that can be drawn on the basis of scientifically accessible evidence—for example, that mutation is random and adaptation turns on the throw of dice–and the meaning(s) that religious believers elaborate for themselves or their communities based on such evidence. Thus, I could imagine that with a bit more theological training that stresses the value of integrity and wholeness, your Christian biologist might be able to explain that mutations appear random from a scientific standpoint, but that—in light of their belief in a creator god—they don’t think that they actually are. They would need to concede, however, in my view, that they can’t demonstrate their claim scientifically but are stating it as a matter of faith.

Although I haven’t developed that aspect of it, I think we can and should consider the implications of valuing methodological agility in different institutional contexts. Here, our two contexts may be illustrative. I am assuming from what you’ve said that the faculty of theology and religion at Oxford would support students distinguishing between the presuppositions that govern biological research and those that govern their Christian faith and allow different conclusions regarding the evolutionary process from these respective standpoints. I can also imagine that those who belong to more conservative traditions might be met with resistance from fellow believers who are unwilling to concede the premises of biological research.

I approach methodological agility somewhat differently at UCSB, which is a public university, than I did at Claremont, where I taught students from a private graduate university and a denominationally sponsored school of theology. In that context, theologically oriented students had the option of developing their theological views in the way that you describe. In a public university, where I currently teach, I don’t see that as part of our task. Within the public university, theological reflection is primarily an extracurricular activity and, in that sense, perhaps compartmentalized. For me now, methodological agility is more a matter of facilitating the ability to shift between humanistic and scientific perspectives. In light of your own research, it strikes me that we both value this ability to shift between different disciplinary points of view.

Ward: Yes, we do, and Oxford too is a public university. I’m not directly involved in seminary education. But nevertheless it is theological reflection that I teach. There are some theologians who aspire to a “pure theology” and for whom that reflection is primarily an internal one: with reference only to the coherence of the Christian faith, say, from within that faith. Much systematic theology is perceived along these lines. I don’t teach theology in that way because I don’t accept there can ever be a purely “insider” account. The insider position is lived in complex situations and draws upon any number of discourses and sciences to understand those situations that impact one’s faith. This is why the pursuit of integrity is important, especially when those “insider” accounts are being legitimated by a variety of institutions, from churches to university departments. How does that faith hook up to the world in which is it held and formed? Acknowledging other perspectives and standpoints is part of recognizing that lives are not and cannot be lived entirely from within the faith without significant cognitive dissonances.

So perhaps there is a difference here between what can be done to shift perspectives in an intellectual project and what this involves in terms of one’s personal development. As a researcher, I draw heavily upon anthropology, sociology, philosophy, cultural studies, and theology, but I want to be upfront about my disciplinary and existential standpoint as a theologian. I’m not aiming at a comprehensive view from nowhere. That would compromise my deep sense of being limited. I build an argument, these other disciplinary voices help me to build my argument, enriching and critiquing it. I can’t speak as an anthropologist or as a sociologist. I rely on the expertise of other people, and I’m aware that I have been selective about whose expertise I have drawn upon, and, therefore, I am open to contestation both within my field and by experts in the fields I have drawn upon. That’s okay. In fact, it seems to me that is healthy. We’re all involved in continuing debates, but the goal is to draw as close to a truth about what is and my faith is part of that truth.

Disciplines: Theology, Religious Studies, and the University

Taves: You’ve indicated in our conversations that you think that theology must be pursued within the context of religious studies. Can you explain why you think this is so crucial? Is it primarily a means of keeping an “outsider” perspective in view?

Ward: In my view, no Christian theology today can be written honestly and responsibly that does not reflect upon three evident realities: a) there are other, long-standing pieties, many religious; b) Christianity itself is far from being homogenous; and c) syncretism is unavoidable. Psychology and sociology of religion offer important counterbalances to theology; critical and literary theory offers essential tools for analysis. A purely “insider” theological account runs into all the dangers of ideology. The biggest challenge in teaching theology is radicalization. If, heuristically, theology is an insider’s discourse and religious studies the outsider’s discourse, then to recognize the outside is already at play in the inside (and vice versa), and to amplify the outside within for greater critical awareness is the first step in being responsible to the rest of the global community for one’s own believing and speaking.

Taves: In a parallel fashion, I have been arguing that we need to pursue religious studies within the context of the range of university disciplines: humanities and sciences (social and natural). Like many before me, I have been arguing that we need not—and indeed should not—limit ourselves to descriptive, phenomenological, or historical studies of religion, but we can and should also seek to explain what we study in terms that make sense to us. As long as we have a clear idea of what we are explaining based on a careful analysis of the insiders’ points of view, are explicit about our explanatory presuppositions, and signal clearly when we are attempting to explain rather than describe, I think we can advance any explanatory account that we think we can defend on general academic grounds—and then submit that for debate and critique. So I think that theological explanations can be advanced in a university context if they meet those criteria.

But I am not sure what this implies about the relationship between theology and religious studies. You indicate that you think theology needs religious studies, but does religious studies need theology in the same way? Is the relationship reciprocal?

Ward: Religious studies does need theology, particularly when trying to understand activities that form the basis for ethnographies or in the interpretation of data and method in fieldwork. Questions put to practitioners have to understand not only the system of beliefs in the books but also the way those beliefs are lived, reinterpreted, and ordered according to certain cultural values. In part this goes back to my concerns with radicalization. Due to numerous years of secular thinking and the privatization of religious belief, religious studies still tends to underestimate the power of religious conviction to motivate action. It underestimates the emotional communities it fosters. Theological conviction is not private and cannot be made private because of the public and open nature of worship and ritual. It is also profoundly political. Religious studies that doesn’t engage with the variety and variation in belief (even within a single piety) risks a reductionism that falsifies or distorts claims that might be made. No anthropologist would engage in fieldwork in a specific location without first trying to understand the “insider” perspective and testing that perspective against more official and authorized descriptions of a specific culture. So the process is two-way.

Taves: I see what you mean, but I want to insist on what I see as a crucial distinction—one you may not embrace—between understanding the theological views (implicit and explicit) of those we are studying and doing theology. If we are going to study religious people, of course we have to understand their point of view, and this includes in the ethnographically rich way you describe. I realize that some who study religion from social-scientific perspectives, whether psychological or sociological, don’t always spend much time doing this, and I agree that is a weakness, but I take for granted the necessity of understanding the religious views of those I study. As one trained in the historical and social-scientific study of religion, I cannot—and do not desire to—speak as a theologian. I do, however, draw on the work of theologians in so far as their work helps me to better understand those I am studying.

This raises a related point, given my interest in studying unusual experiences both as a historian and in light of scientific research. In reviewing my forthcoming book in which I devote separate chapters to both historical and explanatory approaches, a historian friend characterized the chapters in which I advanced a scientifically informed explanation as theological simply because I broke with the historian’s role—which she and I both understood as focusing primarily on the views of others—to offer an explanation that made sense to me in light of current scientific research. I agree with my historian friend that there is a parallel between doing theology and doing science in that both advance explanations based on fundamental premises and values, but, while there may be some cases of overlap, I assume that in most cases they presuppose different ultimate causal explanations based on different sorts of evidence.

Within the natural sciences, the theory of evolution generally provides the ultimate causal framework. Most religious traditions offer an alternative ultimate causal framework—an alternative narrative of human origins—that grounds the tradition as a tradition. The latter accounts tend to be self-authenticating in so far as traditions claim that they were inspired or revealed. The theory of evolution, by contrast, is based on archeological and biological evidence. This is not to say that these frameworks can’t be combined, as, for example, in the case of the Christian biologists we have been discussing. But the biologist as Christian brings specifically Christian beliefs to her understanding of evolution—for instance, faith that God exists and is responsible for creation—which she holds in common with her coreligionists but not with biologists qua biologists. In saying this, I am assuming that scientific and theological causal frameworks rely on different sorts of evidence for the ultimate claims they advance, such that the former is more restricted than the latter. Since our task here is to talk about values, I would say that, when it comes to invoking ultimate causal claims, I value clarity with respect to the kinds of evidence that can be marshaled for ultimate causal claims and sensitivity to the kind of evidence that is relevant or admissible in different contexts, when advancing such claims.

So let me conclude by asking whether, in your view, theological integrity requires religious believers to make something like the distinction I am proposing here between kinds of evidence?

Ward: Yes, theological integrity does require us to distinguish between kinds of evidence. But as a theologian doing theology I can’t make such a neat distinction between “ultimate cause explanations” as you suggest. From where I stand, I am very aware that the very categories that appear to self-authenticate theology (revelation, inspired sacred texts, etc.) are deeply complex issues endlessly debated within theology as it engages with other perspectives about the way things are. The very grounds for any assurances of self-authentication are contested and contestable and, to my mind, rightly so because that enables the closed-circle of ideology to be continually interrupted.

The audio of this conversation, including Thomas A. Tweed's introduction and the Q&A session, is available via RSN's feeds on Soundcloud and iTunes. RSN thanks Ann Taves, Graham Ward, and Thomas Tweed for their permission to print this dialogue.

References

Taves, Ann. 2016. Revelatory Events: Three Case Studies of the Emergence of New Spiritual Paths. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tweed, Thomas A. 2016 (forthcoming). “Valuing the Study of Religion: Improving Difficult Dialogues within and beyond the AAR’s ‘Big Tent.’” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 84.2.

Ward, Graham. 2014. Unbelievable: Why We Believe and Why We Don’t. London: I.B. Tauris.