Growth, Identity, and Branding in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Alabama

Russell McCutcheon, Chair, Department of Religious Studies, University of Alabama

Years as chair: 11

- University Type: 4-year, public

- Student Population: 36,047 (30,752 undergraduate)

- Department degrees conferred: BA

- # Majors: 50

- # Faculty:

- Tenured or tenure-track: 9

- Nontenure-track full time: 1

- Part time/Adjunct: 3

Is there a departmental identity at UA? That is, in the wider world of religion departments in the US and Canada, does the department strive to have a distinct character in its theoretical or methodological orientation or leanings or faculty makeup?

Our department is very conscious of defining itself—both within the national field as well as among other units on our campus that also happen to offer courses on religion. Given that we were a very small department for much of our almost fifty-year history (three or four faculty members), other departments understandably own such courses as Anthropology of Religion, Philosophy of Religion, History of Christianity, Mythology, and Roman Religion, so ensuring that we establish an identity and thus a domain for our department—especially as we’ve grown over the past fifteen years—has been high on our list of priorities.

That we might have lost the major back in 2000, when we were not graduating enough students according to our state credentialing board, means that reinventing the department from the bottom up has kept our eye on identity issues at countless sites. Our view is that theory isn’t some sort of optional second step. Theory provides the enabling conditions for all scholarship (and, in our case, social theory), and it is something that we think sets us apart. So we’ve developed a common and explicit focus on identity-formation (though it’s something our faculty members each study and teach in a wide variety of regions and eras, of course) as something that we think sets us apart from many other departments in the country. In fact, anyone paying attention to our social media or even our job ads will know that there’s a particular sort of thing happening in the study of religion at Alabama and, so far at least, it has been quite successful. Given our success–we’re adding our tenth tenure-track faculty member this August, and we’re hoping to search for another new line next year–I’d hope it’s a model others would consider if they’re game to rethink their own work and departmental identity too.

Some departments work on their public personas through events, outreach, etc. Is this something your department does, and if so, how? Is there a strategy to the way you communicate to wider publics just what is the Department of Religious Studies does?

During my job interview to be chair, back in January of 2000, the newly appointed dean of the College of Arts & Sciences asked me who the various stakeholders were in the study of religion. That’s a key question, I think, for any successful department, so I’d hope all departments work on their public persona. Being a public university, our stakeholders range from the taxpayers of the state to the students and their parents, along with other colleagues (on and off our campus) as well as administrators, the general public, and even our own graduates. So while communicating effectively with them all at any one given moment is likely not possible, we try to think through strategically who this event is for or at whom that mailing is directed and for what purpose. All of this means that the department has a number of different personae, much like each of us, and the key is knowing when and how best to operationalize which.

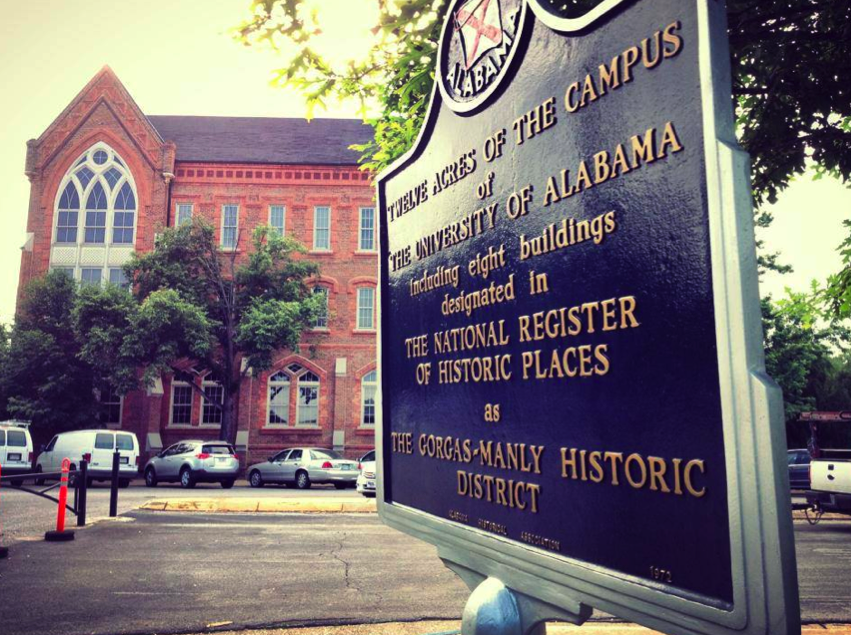

It’s likely linked to your first question as well. It might sound crass to some, but among my first tasks when I became chair was to develop a motto (the result: “Studying Religion in Culture” [the italics matter to us]) and a logo (based on our post-Civil War gothic building and not a mash-up of world religions symbols). The people who poo-poo this sort of intentional branding strike me as missing the point that the nation-state has a flag and an anthem for a reason—how many years of people’s lives do they repeat the Pledge of Allegiance out loud and in front of each other each morning? Publishers don’t pay attention to book cover design and scholars don’t invoke the titles “Dr.” or “Professor” without reason. So for any social group to be successful, a host of techniques are needed—that’s the social theorist in me talking—since I don’t assume group identity is a naturally occurring resource.

So yes, we’re very mindful of our publics and trying to stay in touch with them. Some events may just be for majors, for instance, hoping to benefit them intellectually, sure, but they also provide a social occasion for them to bond as a group. We’re also sure to live tweet it, probably post a picture on social media, and maybe even request some financial support from the college—all an effort to ensure that wider groups understand the good work we see the students and faculty to be doing.

We also learned long ago that although we try to provide programming to attract others’ interest outside our department, whether from the local community or other faculty on campus, we also have to make programming choices based on our own needs and interests instead of trying to intuit what others think the study of religion ought to be. While we work hard to translate what we do to wide publics with our annual newsletter and department blog that features a steady stream of student and grad along with faculty posts, we also have to speak mainly to our primary public—our majors and minors, in and outside of the classroom—for they’re the lifeblood of the department; in the state of Alabama, at least, the number of grads is the crucial measure of viability. And sooner or later, even parents who might have at first questioned their children’s decision to major in REL come around once they see not only the attention their daughters and sons get but also the critically important tools they acquire in our classes. In fact, one of my favorite videos (did I say we have a Vimeo account and that we train students to make movies?) was filmed with two grads (a brother and sister) and their dad, who were all on campus for a Saturday football game. Hearing what dad thought now about what his kids studied in college (one became a public school French teacher and the other a lawyer), versus what he thought long ago when first hearing they planned to be religious studies majors, was pretty gratifying.

So a strategy? Sure: use whatever is available, easily at hand, to make connections for people who aren’t already experts so that they can understand the relevance of whatever seemingly esoteric topic you happen to have trained in as a scholar. It takes time and energy to do, but it pays off in countless ways. At the end of the day, no field is self-evidently important. Our campus closed the Department of Sociology just a few years before I arrived, just as all the languages and even Classics were rolled into one major, and the undergraduate degree in Physics was also nonviable and in need of reinvention. Every communication has a pedagogical undertone, trying to bring people along who might not otherwise care as much as you about this or that. I think of Jonathan Z. Smith’s work here, actually: as I read him, pretty much all of his essays are pedagogical, inasmuch as they exemplify for readers how they too can think more carefully about, say, doing comparison (wherever they happen to do it). I think that’s the spirit of our department—we try to see much of what we do, regardless the intended audience, as having an eventual pedagogical pay-off.

UA has a large undergraduate enrollment. Where and how does the department fit into UA life? Is partnering or engaging with other departments an important part of programming?

In terms of courses, presumably like many departments, our main contribution is to serve what we call the Core Curriculum (or what others might call General Education courses)—either offering lower-level core “humanities” courses for incoming students or upper-level core “writing” courses. We offer other courses too, such as upper-level seminars mainly attended by majors/minors, but the majority of our classes carry a core designation. As others know all too well, these so-called service courses are also the main gateway classes to the major since the vast majority of incoming students have never heard of what we do, and so few are chomping at the bit to declare REL as their major when they first arrive. Our campus doubled in size over the past decade from about 18,500 when I arrived in 2001, so we’ve had to be prepared to seat an always larger number of incoming undergraduate students each fall for quite some time. Our contributions to teaching those students was crucial—we’re hardly the largest department, but the core and honors seats we offer provide a real service to the university.

Like I said, there are far larger departments on our campus, but I bet there are not many who so consistently have their faculty step up to take on major service roles outside the department. I recall earlier in my career offering an invited lecture at UCSB where Richard Hecht, who was chair of that department at the time, took me to lunch. We talked about the field, and at one point I asked what he thought made his department so successful. Without batting an eye he replied by talking about the senior leadership role their faculty played all across campus. That stuck with me. Seating incoming students is certainly important, yes, and each faculty member’s research productivity is crucial, but its takes a lot more to run a university. We help the college to administer its grants programs and a variety of other initiatives, REL faculty serve on its tenure and promotion committees (Merinda Simmons is doing just this sort of heavy service lifting this year, in fact), or maybe the department reassigns faculty time to help the college cover another unit missing a department chair for a semester, perhaps supports a colleague to direct a minor for the college, or we might share yet another faculty member’s time and expertise to help the college promote the use of technology in teaching. The pay-off for doing this is never sure, but apart from just trying to be good citizens it comes back to Hecht’s point: it never hurts a department’s members to have the rest of campus see them as not only principled in the way they practice their field but also as a go to place when things need to get done. It doesn’t guarantee success but I think success can’t happen with out.

As for other departments, apart from Nathan Loewen being reassigned to the College of Arts and Sciences for nearly half his time, working on the above-mentioned technology initiative, we have two other cross-appointed faculty (Ted Trost is appointed 25% to New College, where self-designed, interdisciplinary majors pursue their studies, and Eleanor Finnegan is 25% History), so cooperating with other units is bred into the bone, as the old saying goes.

It’s a tricky exercise since the structure of the university ensures that departments are all competitors—there’s only so many students to go around and there’s only so much money in the budget, yet everyone wants more majors and a new tenure-track line. So intradepartmental cooperation, in my experience, happens on one level but, at another, it’s not as likely. While we chip in to help fund each others’ events, maybe crosslist some courses, and surely develop a number of fast friendships, departments don’t always approach things from the viewpoint that we’re all pulling the same sled. Because the study of religion also happens in other departments on campus, when we redesigned our curriculum about four years ago, we built in twelve hours of electives that, with our advisor’s permission, students can count toward their REL major. This revision encouraged double majors, which is great, but it was also our way to grapple with students satisfying an interest in the study of religion in units other than our own. With the number of majors, and thus grads, being the coin of the realm (along with total credit hour production), these things matter a great deal in the long run.

On campus at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa

On campus at the University of Alabama in TuscaloosaAre religious studies courses available to students to satisfy core curriculum requirements? If so, how do leverage that opportunity?

Since having students find us often happens through satisfying their core requirements, then the more lower-level core courses (or upper-level writing courses) the better the chance they’ll find us. So over the past few years faculty have been proposing new courses and identifying many as new core courses. Doing so introduces the faculty member’s area to lower-level students and, hopefully, lays a foundation for a possible repeat visit in one of their upper-level classes later. Since satisfying one of the core’s writing courses is also something some of our upper-level courses do, it means that students from a wide array of majors end up enrolling to satisfy that requirement—thereby making those seminars feel a bit like an introductory course, unfortunately. Although this presents some challenges to faculty, I think we all also realize that because we need the enrollments for the upper-levels many of those courses have always had that feel to begin with.

This comes back to an earlier point, actually—the pedagogical intent in many of our classes. Because we propose an alternative to how people usually talk about religion, then many of our courses must work from first principles to make sure everyone is up to speed with the issues that need consideration if we’re going to talk about this tale or that behavior in this rather than that way.

As I mentioned earlier, these service courses are also gateway classes—but it’s not like students, having taken a 100-level introductory course, immediately declare a major. Far from it; after getting the three credit hours from us, most never darken our doorstep again. That’s just the way it goes. But some do, and most who do end up doing that a year or two later. We have a number of students declare their major in the junior year because they recall a good experience in an intro course with us, a couple years back. So in many cases the gateway has a delayed reaction.

When a faculty member agrees, we’re sure to use intro course to offer other events in the department as extra-credit opportunities. This is controversial, but if part of what we’re doing in these core courses is introducing students to university life, then maybe we all need assignments that get them going over to the library or ways to incentivize going to an evening lecture by a visiting scholar. Whether or not that recruits the student to our field, it might at least help to plant the sort of seed that is needed to be curious about the world. If nothing else, I’d hope that the university is a place premised on that sort of curiosity. So students in these courses appear at our annual undergraduate research symposium to hear their fellow students present original research, and they end up at our evening Grad Tales events where we invite recent grads back to talk about their incredibly varied careers and the role they think their liberal arts training has played. We also see them at our annual and endowed Day and Aronov lectures. Investing this kind of energy is, we think, among the prerequisites to hopefully finding them enrolled in another one of our courses—someday.

Let’s talk more about recruitment and marketing. How do you sell your department to potential majors? What’s your relationship with social media and digital media technologies?

Back in 2001, when I came to Alabama, we had a pitiful website. Nothing matched; it had little info, only a few pages, and all in multiple formats. So among the first tasks was reassigning my then colleague, Kurtis Schaeffer (now chair of religious studies at the University of Virginia), to build us a decent site. His efforts, using a preset university template, bought the department a year or so during which we commissioned a new design and got the logo made. Soon after, we had a professional-looking site that, over the course of a few years, grew to several hundred web pages. These were the days well before Facebook, of course, so we updated the site often and students routinely went there to get information on the department (upcoming courses, lectures, pictures/captions from a recent student event, etc.).

Now, with the advent of Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, not to mention our blog, the challenge is how to have a presence that reaches out to varied audiences while ensuring that the message always reinforces who we are and what we do without being redundant. In fact, this is now a major service assignment in our department, with Mike Altman taking the lead. But many hands make light work, and twice a semester, a different faculty member will also occasionally tweet for an hour from our department lounge—Live Tweets from the Lounge, or #loungetweets, is what results. And many of the faculty regularly tweet (or set up their own class blogs and Twitter accounts); so if you happened to be online and, for whatever reason, paying attention to our department in early March you might have seen Steven Ramey, Merinda Simmons, Eleanor Finnegan, Vaia Touna, Nathan Loewen, and Mike Altman all tweeting about our undergraduate research event, and tagging our @StudyReligion account meant that the retweets were happening fast and furious. But the best part of all is seeing our students get into it as well and, sooner or later, people from well off campus chiming in, commenting, elaborating, seeking feedback, and, voila, something happening in a room in Tuscaloosa is relevant to someone sitting in an office who knows where around the world.

Like I said, it’s all about making sure students know that what we and they do matters.

But apart from a pretty strong social media presence, we do a variety of things to get the word out. We’ve sometimes put a catchy ad in the student newspaper, but who knows what the return on that is; so we also book space on campus each semester for a few hours, to put up the department tent and advertise upcoming classes. We get some fun buttons made, pin them to a business card with course information and a QR code that takes you to our website, and our student association has fun giving them out to people who are on their way to the student union for lunch. These button events, as we call them, were the idea of Steven Ramey and Eleanor Finnegan, as I recall, and they’re an opportunity for the students to bond and have fun. We also do this during “Get on Board Day” at the start of each semester, a time when student clubs come out to recruit members from new incoming students. So, like I said, we hope to get the word out about us, sure, but it’s also a chance for our own students to increasingly feel part of the department themselves—they’re in it with us and having them know that doesn’t hurt. You’d be surprised how many return visits we get from people wanting this year’s button!

Of course, faculty talk about upcoming courses in their classes, but we’ve learned that’s not enough. You’ve got to make an appointment and go over and talk to the admissions staff and campus recruiters; you’ve got to talk about the department to the advisors in your college; you’ve got to get a flyer of upcoming classes into people’s hands and posted online; you’ve got to invite some blogs from grads concerning what they now value about what they did way back when. The payoff on all these investments is never really obvious, but it strikes us as serving so many needs that I think we now can’t imagine not doing it. So in a faculty meeting you’ll hear “When’s the next button event?”

How reactive is your curriculum? How do you gauge and respond to student demand while satisfying institutional requirements and department values? And how do you gauge the success or failure of curricular changes?

That’s a tough one, since it often takes several years for a course or even a new faculty member to establish themselves in the curriculum. Given that we don’t control many of the variables that affect things, for example, when courses that compete with our own are scheduled, it can be a hit and a miss. But like any department we have a variety of topics courses at the upper-level, and even our intro courses have a degree of adaptability, so it isn’t difficult to have a course on the books the very next semester if something happens that faculty feel needs to be addressed in the curriculum. Within a year it could be regularized as a course, if they’re game.

However, the department sees itself as swimming against the stream a bit—and as bringing students along with us—so I’m not sure the idea of student demand is necessarily how we make curricular decisions. We aim to be timely, but more than that, we aim to persuade students that studying religion as self-evidently interesting is not nearly as fascinating as paying attention to what gets called religion (or Hindu or Muslim or dominant or marginal) and how systems of designation and identification are tied to all sorts of other issues in a society—“classification is a political act” our students now tell us. And doing that seems to us to be the goal of a liberal arts degree—persuading students to become curious about their world in a new way and then seeing what they’ll do with these tools.

What’s your philosophy on the role higher education—and a student’s chosen major—should have on career prospects?

We tend to have in mind a student as an entrepreneur, but not necessarily in the business sense, of course—maybe bricoluer is a better image. For while some of our graduates will enroll in further degrees in our field, many go into such a wide variety of careers that it’s tough to itemize them all. From law and medicine to teaching and business, our graduates have successfully done so many different things that it reinforces our view of ourselves as using the topic of religion as a site where we teach skills (e.g., definition, classification, description, interpretation, explanation) that are widely applicable, all depending what the student wishes to do. It also fits well with the image of the liberal arts as readying a person for life—not necessarily that old Renaissance notion of the good life, whatever that is, but, instead, any old life where distinguishing and ranking and acting (and then being prepared to deal with the consequences) happens countless times a day.

While there are some programs in the modern university that are very career oriented—if you want to be a civil engineer, then you must take these classes, in this order, and then write this credentialing exam (whose contents were covered in all those courses)—the study of religion can be like that, for those who wish to enter this profession, but for most of our students, it isn’t. And for them we are convinced that it’s the skills that we teach which will be remembered and used; they may or may not retain the name of this river or that god, but they will more than likely remember that any two things are comparable if seen in this or that way, and that they themselves play a key role in determining how these two things are put beside each other (or not).

I don’t want to sound too Pollyannaish, but I really do think the sky’s the limit for our students so long as they make the shift and understand that their classes with us, on any number of different topics, are all examples and thus places where a certain way of talking about human beings can be done in order to shed new light on a situation. Our hope is that, in the future, they’ll use the method (what I guess we once called critical thinking?) on sites in which they have investments and curiosities. What those will be, who knows? The students who “get” this really are motivated by our approach; the students who don’t at least gain the descriptive information that they came for when enrolling in a course on world religions, for example. Luckily, some keep up with us and come to see that it’s our very habit of calling some things “world religions” that we find interesting.

How do you advise students interested in pursuing an MA and/or PhD in religion?

Annually, we have a graduate school prep evening or workshop, ideally in the spring, when students get to talk with faculty about the nuts and bolts of applying to programs: taking the GRE, how to write a cover letter, what to put into a CV, and how to pick a school to which they’ll apply. Throughout the year, I know faculty are talking with students interested in further study. There’s a variety of backgrounds in our own department (e.g., several faculty, including myself, started their careers as nontenure track instructors), and a student would have to work pretty hard to graduate without being told to think seriously about national trends in higher education and the humanities job market in the United States and elsewhere.

While I can’t speak for all of the faculty, my guess is that practical pointers are high on the list, making sure students interested in further study know that student debt should be on their mind, that gaining practical professional experience should also be there (will they get experience TAing in this or that program?), while they should also be aware of programs that likely depend too greatly on grad student labor. After all, while having some teaching experience is important once you near the end of a PhD and are ready to get on the market, having taught five or six or ten or twelve (or more) of your own courses at such an early stage might not add up to as much as you think. The learning curve on teaching your own class is steep, but it can flatten out quickly, and although hiring departments are certainly looking for evidence of classroom success, they’re also looking for plenty of other things on those CVs that come with applications.

We’ll never pop the balloon of a student’s excitement and hopes for the future, but I think it’s fair to say that all of the faculty work to make sure grads see higher education as an institution much like any other, with practical constraints and power issues that need to be taken into consideration if you wish to enter it. In my fifteen years here, we’ve had some students go on to earn further degrees, to be sure, and I’d hope they’d all agree that, though there’ll inevitably be surprises, they all went in with their eyes open, ready for both the potholes and the opportunities.

Have you done any hiring lately? What’s your impression of the academic job market, beyond the obvious competitiveness of the pool?

We were 4.25 tenured or tenure-track faculty back in 2001 (back then I was the sole tenured faculty member) and in the fall of 2016 we’ll be ten (five of whom are tenure-track), so we’ve been quite successful in obtaining new lines and making strong hires. As I also said earlier, the university doubled in size during that time, but because we were threatened with losing the major back in 2000, there was no necessary reason the resources had to come our way. I’m still thankful that our then brand-new dean decided to invest in the department, by hiring an outside chair (the position I serve), instead of closing us.

Unlike, say, English, which has four required English courses in the core curriculum, or History, with two of their own, there’s no reason a student has to take an REL course (though they can choose to, if they like, and obtain core credit, of course). So for us to grow our faculty was a challenge to persuade the university that we were helping it to meet its goals while also meeting goals of our own—even as they don’t always overlap. Because campus growth was an overarching goal of the university, demonstrating increases in credit hour production was the key. We’re now teaching about four or five times the number of students annually that we did back in 2000—some of those are online (where we have three off-campus staff who grade courses), but the vast majority are in in-person lectures and seminars. Over the years we’ve had quite a few searches.

One thing that really stands out for me, and something I’ve written a little bit on, actually, is how unprepared I find many early career scholars to be. They know much about their area of specialization, but their ability to communicate to people outside that specialty is sometimes a challenge for them. It always seems to me that—returning to that notion of pedagogy—the whole interview is more similar to a set of practice teaching sessions than candidates realize; their casual conversations and even their academic paper (should that, and a sample teaching demonstration, be part of the interview, as they are for us) are opportunities to demonstrate their ability to bridge a gap between what they know and someone who doesn’t know it. But too often I meet very bright, very motivated people who haven’t yet been challenged to think beyond their data domain. It’s long been apparent to me that departmental identities are built at the level of theory, not data, and so, ideally, the reason we happen to have offices next door to one another is not because we each study the same ritual but because we both see our examples as just that, examples—illustrative of something that people do rather widely.

Too few people on the market today seem to understand this.

When our department puts out an ad for “social theory of religion and X” (as we’ve recently done a couple times)—that is, specifying the approach we’re looking for but leaving the area, period, topic wide open, it seems that many people overlook the ad because religion in America wasn’t mentioned by name, or neither was Islam or Siberian shamanism, etc. It means to me that doctoral programs in our field are probably all still working in world religions boxes, and anyone who challenges that model, by asking why studying this or that myth is interesting or relevant, can be greeted by blank stares and repetition of the descriptive details. We’ve had a lot of success with our approach though, and I’d hope others would rethink that model and challenge doctoral programs to produce more crosscultural comparativists who are interested in answering broad questions by means of their narrow focus.

How do you think the field of religious studies is doing?

Tough to say. On our campus, it’s doing wonderfully, though we still have a variety of challenges. We’re in the midst of proposing a new MA degree that takes social theory of religion and the communication skills of the public humanities equally seriously. If all goes well, the program will start in the fall of 2017, but there are plenty of committees and hurdles to pass between now and then. So at least here at Alabama, the field is thriving—something I particularly like to say, I admit, given the negative stereotype so many in the United States still have of this state.

Nationally? I’m not so sure. I helped to organize a meeting of public university department chairs at the last AAR, in Atlanta, and about fifteen attended, from some of the big schools in the country, and it wasn’t difficult to go around the room and hear tales of woe related to oversight, governance, funding, credit hour production, retention, recruiting, etc. No tale was unique, of course—it’s a story told by many in the humanities. But I sometimes think that departments that are not adaptive or are not intentional about how they are seen and how their skills relate to wider interests among their students, might be in for some big challenges in the future. All this depends on what you mean by religious studies, of course; if you mean by that something other than what we aim to have our department accomplish, then you might conclude that the field is doing really well.

Speaking as a department chair who takes seriously that not just the ability to satisfy intellectual curiosities but also the ability to have careers and to pay mortgages and raise families all depend on what we do in departments, I’d simply say that it’s the long-term good of the field that our decisions today ought to be anticipating; solving a short-term issue is key, of course, but ideally we’re making decisions that will leave departments in the future who will one day be hiring the undergrads we’re today teaching.

The recession had an incredible impact on public universities and colleges. How was your department affected? Is there a “new normal” when it comes to funding in higher education?

All the campus growth over the past decade means we’ve had resources on our campus and, in many ways, didn’t really feel the 2008 collapse all that much. We didn’t have raises some years, but the rate at which we’ve been hiring new positions stayed steady or even increased. Our university’s growth plan put us in a good position to weather what other public universities that still largely rely on state appropriations could not. While this doesn’t mean that we’re somehow awash in money, it does mean that the administration has been able to address historically low salaries here, as compared to the South University Group (those against whom we measure ourselves when it comes to thinks like salaries), and that new positions have indeed been given to departments that can demonstrate they’re helping the college and the university to meet their goals.

What’s something you’ve learned as chair that you didn’t know as a regular faculty member?

Hearkening back to something I mentioned earlier, about job candidates: I think many faculty also are trained to focus on their data domain and subject area (the silo model), whether in their research or teaching. I recall an experience with someone once presuming that we’d of course get a replacement position for an Asianist (a vacancy made when Kurtis left for UVa)—it’s Asia, after all, I was told, and we all know just how important it is to study Asia, right? Now, while not disagreeing over that particular importance (and our campus indeed has too few Asianists—which is just one of the reasons why we’re so pleased to be adding Suma Ikeuchi to our faculty this coming Fall, inasmuch as she studies the role played by religion in identity formation among Japanese/Brazilian immigrants), I recall answering by saying that this importance would likely not necessarily be among the reasons for us getting the position—if we were lucky enough to get it, that is. This decision would probably be made using other scales of values—credit hour production, graduation rates, student-to-professor ratios, research productivity, grant success rates and external funding budgets, and whether the desired position helped the university to achieve its goals.

My point is that thinking well outside one’s own data domain is a necessary skill for anyone interested in helping a department (that is, helping one’s students and colleagues) to succeed today. And this is maybe not all that apparent to some faculty members. It doesn’t mean leaving your research interests behind but, instead, learning how one’s own focus is somehow interrelated with other things that others think are no less important. That’s one of the key things that I’ve learned as a chair; a field-wide interest is something I came to the job with—in fact, that’s what prompted me to apply in the first place. But an institution-wide awareness, well beyond your own field, let alone own research, is what you need, to be able to anticipate opportunities and see overlaps that advance your unit’s interests. And those “other things” are not just the work of your peers or the curiosities of your students but goals other departments are working toward, the aims of administrators further up the chain, as well as the goals your department might have in some imagined future that you’re working toward.