The Politics of Christian Theological Education

[Author’s note: In this piece I write out of a particular set of Christian convictions about the purposes of Christian theological education. Such starting points, and such scope, are of course narrower than the full range of starting points and concerns of members of the Academy. I do not presume to speak for others with other starting points or interests, let alone for the full spectrum of membership. But I do hope the essay might open up some points of conversation across lines of difference.]

Much of my energy for this work comes out of a conviction that we are in the middle of a sea change in theological education, the kind of shift that has happened about once a century in the United States over the last 300 years. If the energy comes from a sense of change, the particular shape of the project comes from the repeated experience of watching people—myself among them—grapple with this change in mostly managerial language. We talk of enrollment numbers and funding models and relative position in various markets of money, students, faculty, and status. These things matter. The work of a good manager is essential and deserving of respect, for truly great managerial work is not just efficient, but also moral. I hope this project will support wise and good managers in their work. But I have also been worried that our focus on the means was keeping us from conversations we needed to have about the ends of theological education. And so I have tried to keep questions about the ends of theological education at the center of the project. What is all this for? What is the telos of theological education?

Talk of telos can seem trivial and abstract, like the worst sort of academic navel-gazing. This is especially true when theological schools are closing, students are crushed by debt, and faculty jobs are dissolving into the gruel of adjunct work. And now, when some of our students, staff, and teachers fear being deported; when all of our students, staff, and teachers have greater and lesser reasons to fear a militarized police force that will not be checked by a Department of Justice committed to civil rights; when the president says and does things that grant legitimacy to some of the most hateful currents in our culture; when the habits and institutions of democracy are under threat . . . at a time like this, talk of anything but political action with this-worldly impact can seem not just trivial, but decadent. We know what the purpose of theological education needs to be: we need theological education that empowers action for justice. We need theological education that is action for justice. We need to put whatever theorizing, theologizing, or talking about telos we do into the service of a politics of resistance and emancipation.

I feel this demand. Even more, I feel judged by it, convicted by it. And I think we must be willing to take stands that place whatever status we have at risk. We must be willing to give up the rituals of respectability, as many members of the Academy already have. I think the times demand new seriousness from us, new willingness to risk, new faith and energy for bearing witness in a time when the powers and principalities of this age seem to be ascendant.

At the same time, I must confess I worry about the call to put theological education in the service of even the best sort of political action. I worry about it because it invites an instrumentalization of theological education that I think betrays our best hopes for this work. It elevates managerial logic as if by a hidden set of stairs. If the goal of justice is higher than the goal of keeping the institution alive for another year—and it is—orienting theological education to the pursuit of that goal still makes it a means to this-worldly ends. It just asks us to manage theological education in a different direction.

In articulating this worry I do not mean to renounce the political significance of theological education. On the contrary, I name this worry in part because of political concerns. For I worry that our political goals are too small, too determined by systemic racism, too attached to knowledge-class vanities. I worry that they are insufficiently radical, insufficiently utopian, insufficiently hopeful, insufficiently infused with the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. And so I worry about making Christian theological reasoning about the purposes of theological education subject to our immediate practical projects.

The Censor’s Placet

Theodor Adorno is a mixed-bag of a guide on this question. But I think his analysis of the right relation between theory and practice can be instructive to us now. In his Negative Dialectics, Adorno wrote:

The call for unity of theory and practice has irresistibly degraded theory to a servant’s role, removing the very traits it should have brought to that unity. The visa stamp of practice which we demand of all theory became a censor’s placet. Yet whereas theory succumbed in the vaunted mixture, practice became nonconceptual, a piece of the politics it was supposed to lead out of; it became the prey of power.1

Theory, theology, and talk of telos can become, in Adorno’s words, “degraded … to a servant’s role.” This is not just bad for theory. It leaves practice to become “a piece of the politics it [is] supposed to lead out of …” even “the prey of power.” We need tactics to make it through the night. But because the ends those tactics seek are embedded in an unjust order, we also need hopes that go beyond a better president, and the reform of police practice, and the guarantee of Constitutional rights for all people, whatever their gender, sexuality, race, religion, or country of origin. We need to work for these things. But we need to pursue them by the light of hopes that exceed all that we can ask or imagine.

We need dreams of a heavenly city whose gates are always open. We need beatific visions of a God who calls us to arise and come, for winter is past. We need parables of a Reign of God in which all the laborers are paid the same wage, regardless of when they arrived in the vineyard. We need songs of a time when the wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them. Theological education can nurture such visions. And so I think we need theological education that seeks a telos that is not just a better goal, but a hope of another order.

Whose Hopes? Which Rationality?

Saying that theological education should nurture such hopes should provoke an immediate challenge: Whose hopes are you talking about? Who gets to specify the content of these beatific visions? From what social location are these hopes formed? These are the signature questions of our age. For we live in a time when we know there is no view from nowhere. Every view is a view from somewhere. That somewhere is shot through with interests of race, class, gender, and more. The promise of the academy is that it offers a little break from the pressing demands of economy and politics. It creates an institutional space for thought to break free from material concerns. But if the academy shelters us from some sets of demands, it depends for its existence on the fulfillment of other demands that are no less political and no less material. The theological academy is on the grid of power. Why, then, should we expect visions formed in the theological academy to transcend their material origins when others do not? If it’s all already political, shouldn’t we just bring the politics to the surface so that we can deliberate with clearer vision and hold one another accountable for our choices?

These questions grow out of a truthful recognition of the significance of social location. But it is also true that they can play—and, I would argue, they have played—right into the hands of a prevailing order in which neoliberal incrementalism, technocratic managerialism, and nihilistic careerism collude to divide the world between them. When we use the knowledge that every view is a view from some very implicated somewhere to sweep the legs out from under prophets who would sing to us of other worlds, we end up saying “Amen” to Margaret Thatcher’s declaration that there is no alternative.

The recognition of the social location of all knowledge makes any talk of a transcendent hope problematic. At the same time, the loss of such visions consigns us to a world that has given up hope for deep change. This dilemma has dogged me since I first started thinking about theological education more than a decade ago. The institutional crises within schools and the wider political crises that rage in, through, and around schools only make it more urgent.

Yearning

The key, I think, is not to evade the dilemma, but to live into it, even to intensify it. Intensifying the dilemma means accenting both poles of it at once. We must be reminded constantly, forcefully, of the social location of our visions. At the same time, we must be reminded constantly, forcefully, of how much we need a vision that transcends all of our social locations. If we forget social location, we slip into one or another ideology, old or new. And if we forget our need for a transcendent hope, we slip into the ideology of Third-Way realism that is—still, even after a string of defeats in these last twelve months— one of the signs of our times. If we forget the first pole, we can confuse our hopes with God’s hopes. And if we forget the second, we can confuse the limits of what we can do with the depths of what the world needs. Remembering both at once puts us in an impossible situation—which is, I think, exactly where we need to learn how to live.

Learning to live in this space should be central to the formation offered by theological education. It would involve learning in conversation with people different from ourselves, and in critical reflection on our own positions, the particularities and limits of our hopes. And it would mean learning in conversation with scripture, and with wise teachers and faithful witnesses of every era and continent, the need for good news that outruns our ability to proclaim it. It would mean nurturing in students and faculty a desire for a transcendent hope and a recognition that even our best efforts do not offer the hope we need. It would mean cultivating a yearning for justice.

Some might argue that such yearning is itself the favored posture of privileged, tenured, white, male academics, for it allows us to wring our hands and furrow our brows and express sincere concern . . . and do nothing to change the structures that benefit us so much. But the yearning I am describing still takes action, even bold action. It just refuses satisfaction.

Others might argue that such yearning is just nihilism in fancy dress. That might be true, if I thought that all of this was up to us. But I don’t. If Christian theological education has any value at all, it depends on knowledge of a God who is more than just our thoughts about God and whose work for the redemption of the world is more than just the sum total of our actions. Christian theological education presumes such trust is meaningful. More specifically, it presumes trust in one whose power is made perfect in weakness. In light of that trust, we understand our limits differently. In our yearning we are not bereft. Instead I dare to hope that in our yearning our sighs are joined to those of the Spirit who groans with all creation with sighs too deep for words. And in that joining is the substance of theological knowing. Having a right knowledge of our limits does not put an end to wisdom. On the contrary: the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom. And it is the beginning of any Christian theological education worthy of that name.

Notes

1 Theodor Adorno, 2003 (1966). Negative Dialectics (London: Routledge), 143.

Ted A. Smith is associate professor of preaching and ethics at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. He is the author of two books, Weird John Brown: Divine Violence and the Limits of Ethics (Stanford University Press, 2014) and The New Measures: A Theological History of Democratic Practice (Cambridge University Press, 2007), and the editor of two more. Smith serves as director of Theological Education Between the Times.

Ted A. Smith is associate professor of preaching and ethics at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. He is the author of two books, Weird John Brown: Divine Violence and the Limits of Ethics (Stanford University Press, 2014) and The New Measures: A Theological History of Democratic Practice (Cambridge University Press, 2007), and the editor of two more. Smith serves as director of Theological Education Between the Times.

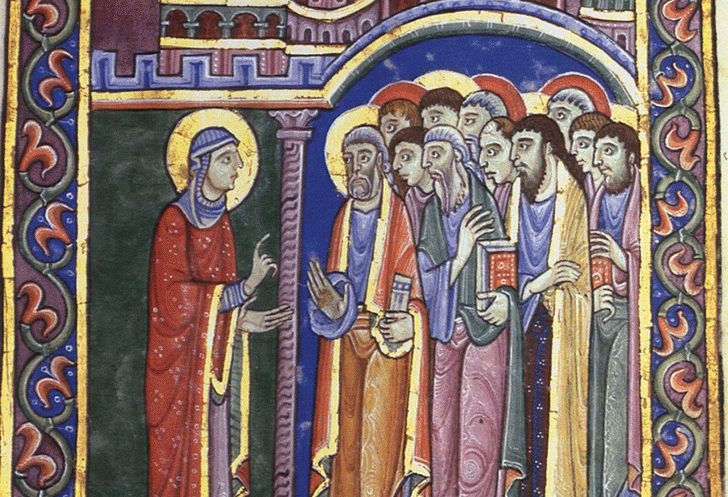

Header image: Mary Magdalene announcing the Resurrection to the Apostles, St. Albans Psalter, 12th century