Realities of Teaching in a Neo-Lynching Culture in 21st Century America

My research on lynching and a culture of lynching in the United States is a painful reminder that theological education is always a negotiation of multiple lived realities. As a black US-born woman serving as academic dean and faculty member at a free-standing United Methodist seminary, with one campus location in Kansas at the largest United Methodist Church in the United States and the other at a United Methodist university in Oklahoma City, 11/9 offered a clarifying moment that there is arguably no static point that defines theological education at any given moment. However, a review of practices—such as qualifying exams, hiring decisions, curriculum revisions—might indicate an unawareness of the manner in which a growing percentage of persons navigate theological education between the times. As a point of clarification, I do not view “times” as a chronological reference point. Instead, I consider how the Association of Theological Schools and the Commission on Accrediting’s shared mission “to promote the improvement and enhancement of theological schools to the benefit of communities of faith and the broader public” influences professional and institutional self-identity and purpose.

Theological Education in a Post-11/9 Era

Prior to 11/9, I did not accept invitations from “well-meaning” Euro-American students to address historical-contemporary manifestations of racism as this country’s original sin. Instead, these student encounters presented as teachable moments to encourage them to name their discomfort and/or dis-ease and to engage in dialogue with my Euro-American “liberal” faculty colleagues about social-historical accounts that are antithetical to the colorless accounts they often so readily accept without question. In this post-11/9 season, I realize that as an administrator and theological faculty member, I do have a responsibility to create space where students can reflect on ways in which they are both compelled to appeal to the moral conscience of the nation and to articulate an ethics of ecclesiology that demonstrates their understanding of the nature, purpose, and function of church and its relationship to Christ and white supremacy.

When I gathered with colleagues in April of 2015 for a consultation on theological education at Mundelein Seminary at University of St. Mary of the Lake, the relevance of black lives was a pressing concern. And it remains one now. It is a moral dilemma that sparked debate about the significance of activism in response to a growing public recognition of the death of unarmed black persons at the hands of persons whose profession is traditionally understood to reflect a mandate to protect and serve.

As I reflect on the results of the 2016 presidential election in the United States, I am reminded that:

- Lynching still occurs, but in different forms.

- Today, the Klan bivouacs without robes and hoods.

- Slavery still exists but under the auspices of a prison industrial complex.

- Discrimination thrives, with no intent or program for relief.

- As was true in the 1960s, it is time for citizens of good conscience to rise up and rally to the cry for freedom and justice for all.

- We must think seriously about how some may view our service to the academy as a transgression, the time we invest to maintaining the status quo for the sin of our soul.

- From a manger in Bethlehem to a Bantustan in Soweto, a bus in Montgomery, a freedom summer in Mississippi, a bridge in Selma, a street in Ferguson, a doorway and shots fired in Detroit, a Moral Monday in Raleigh, an assault in an elevator in Atlantic City, an office building in Colorado Springs, a market in Paris, a wall in Palestine, a restoration of ties between Cuba and the United States, the kidnapping and assault of young school-aged girls and the reported killing of 2,000 women, children, and men in Nigeria, a new generation of dream defenders, a transgender teen's suicide note, our abuse of the environment—the racial climate in the United States, and the respect for our common humanity everywhere, is clearly in decline.

- Theological educators cannot acquiesce, remain silent, or be passive and neutral as people come to terms with an 11/9 presidential election poised to usher in an era of human rights violations from which only a select few will be exempt.

- We cannot continue with business as usual in our educational institutions in the midst of so many egregious injustices.

(Adapted from “An Open Letter to Presidents and Deans of Theological Schools in the United States")1

While there are graduate departments of religion that are not accredited by ATS, association membership is “open to schools located in the United States and Canada that offer graduate theological degrees, are demonstrably engaged in educating professional leadership for communities of the Christian and Jewish faiths, and meet the standards and criteria for membership established by the Association.” A post 11/9 society suggests that “theological education is in a season of profound change.” Informed by institutional identity and purpose, a presenting question is who and what will define that change.

Deepening Conversations toward the Common Good

The American Academy of Religion and Society of Biblical Literature’s Program Planning Committee selects host cities for annual meetings years in advance. It is impossible for even the most seasoned event planner to neither anticipate the significance of San Antonio for 2016’s gathering nor fully account for the dynamics of the 2016 election, including political rhetoric that intentionally maligned and placed at risk a majority of persons who reside in Texas as well as a significant percentage of AAR/SBL members. Although professional meeting planners cannot account for political issues that may influence an event’s ultimate outcome, theological educators will have to determine which motivating factors are of most importance while contending with compliance issues dictated by the Department of Education, ATS, regional accrediting bodies, and other agencies.

As I review the landscape from my own particularities, ATS’s four core values serve as a point of reference by which to understand how theological education remains unchanged while simultaneously adapting to new ways of self-understanding. As global citizens in a post-11/9 era, how we respond to access to health care, building of walls, female reproductive health, immigration, natural resources, quality public education, refugees, religious diversity, and a plethora of other moral problems will convey our core values and beliefs to the world.

In a post-11/9 era in which the only citizens who may be exempt from blatant and potentially harmful acts of bigotry are persons who self-identify as cisgender white heterosexual men, theological education finds itself at a crossroads to think more intentionally about how we prepare persons to engage in conversations that further an understanding of the common good. This emphasis on the collective will require theological educators to redefine, broaden, and nuance our working definitions and approaches to diversity, quality and improvement, collegiality, and leadership. These four key values, as articulated and embraced by ATS, suggest that theological education must be intentional about the ways we view the world and our contribution to the places we inhabit and the people we encounter. For such a time as now, we are presented with a challenge to determine how to negotiate the tension ever mindful of countless examples that conducting business as usual may not serve us, our students, and others well.

Notes

1 Alton B. Pollard III, January 17, 2015. “An Open Letter to Presidents and Deans of Theological Schools in the United States,” The Blog, The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/alton-b-pollard-iii-phd/an-open-letter-to-preside_19_b_6492328.html

Angela D. Sims is the Robert B. and Kathleen Rogers Chair in Church and Society and academic dean at Saint Paul School of Theology in Overland Park, Kansas. Sims’s research examines connections between faith, race, and violence with specific attention to historical and contemporary ethical implications of lynching and a culture of lynching in the United States. Sims is the principal investigator for an oral history project, “Remembering Lynching: Strategies of Resistance and Visions of Justice,” and the author of Lynched: The Power of Memory in a Culture of Terror (Baylor University Press, 2016), Ethical Complications of Lynching: Ida B. Wells’s Interrogation of American Terror (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), co-editor with Katie Geneva Cannon and Emilie M. Townes of Womanist Theological Ethics: A Reader (Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), and lead author of Religio-Political Narratives in the United States: From Martin Luther King, Jr. through Jeremiah Wright (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

Angela D. Sims is the Robert B. and Kathleen Rogers Chair in Church and Society and academic dean at Saint Paul School of Theology in Overland Park, Kansas. Sims’s research examines connections between faith, race, and violence with specific attention to historical and contemporary ethical implications of lynching and a culture of lynching in the United States. Sims is the principal investigator for an oral history project, “Remembering Lynching: Strategies of Resistance and Visions of Justice,” and the author of Lynched: The Power of Memory in a Culture of Terror (Baylor University Press, 2016), Ethical Complications of Lynching: Ida B. Wells’s Interrogation of American Terror (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), co-editor with Katie Geneva Cannon and Emilie M. Townes of Womanist Theological Ethics: A Reader (Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), and lead author of Religio-Political Narratives in the United States: From Martin Luther King, Jr. through Jeremiah Wright (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

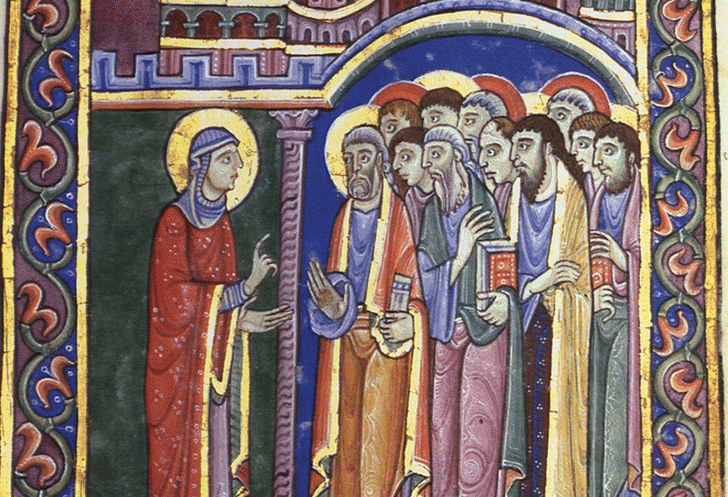

Image: Mary Magdalene announcing the Resurrection to the Apostles, St. Albans Psalter, 12th century