Public Religion Scholarship: The Digital Landscape

Many signs point to a growing interest in connecting religion scholars with audiences outside of academia. One recent indication of this development was the AAR’s 2016 revision of its mission statement to include the "public understanding of religion." Another is the new proliferation of grant funding for initiatives that seek to make the academic study of religion relevant to an American general public who is deeply influenced by religious commitments and discourse. Disinformation campaigns, extremism, and deficit of critical thought across online media make the work of public scholars of religion more important than ever before. In 2020, the Henry Luce Foundation, one of the major foundations supporting the development of public religion scholarship, awarded a team of researchers (including the authors of this article) a $50,000 grant to study public scholarship on religion. The Principal Investigator of our study was Sandie Gravett of Appalachian State University, and as members of the grant team, our task was to conduct an environmental scan of the digital landscape for public scholarship on religion. Where do scholars of religion find public voice? Who occupies those spaces? Who underwrites them? In asking these questions, our goal is to support the expansion of religion scholars’ public reach as well as to help identify existing opportunities and potential areas for new growth.

We surveyed thirty-four sites for public scholarship on religion. These included websites, podcasts, video channels, and hybrid spaces (e.g., traditional print sources with a robust online presence). This report summarizes our findings and sketches the infrastructure that makes the work and voices of scholars of religion publicly accessible.

Authorship and Content Creation

The ecosystem for public scholarship on religion includes both authors and audiences—those who do the writing and those for whom they write. This study found that content creators on sites that feature scholarly perspectives include three primary categories of authors: professional academics, religion journalists, and religious practitioners. The latter two groups contribute to public religion scholarship when they interview scholars or engage scholarship in discussing current trends, recent events, new books, or topics germane to religious practice or thought. Naturally some sites for public scholarship employ multiple voices and not every author speaks or writes in one mode.

Audiences

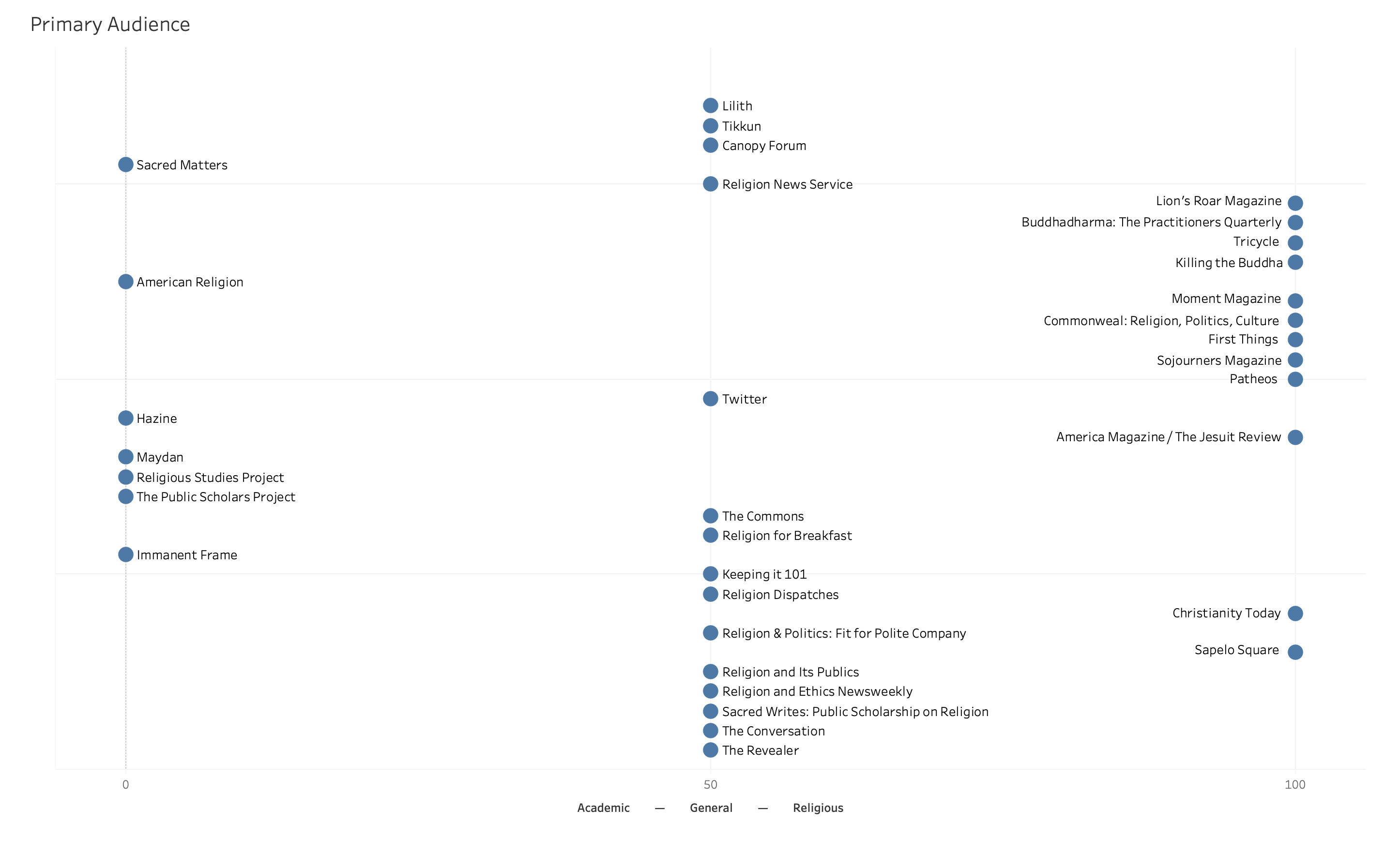

Target audiences may include professional academics, the general public, and religious practitioners. While all of these thirty-four sites we surveyed constitute public scholarship by virtue of being publicly accessible, some speak in more scholarly vernacular and some in the language of religious insiders. Most also aim to speak to a general readership, with some material created specifically for general audiences. The Conversation, for example, is a “non-profit, independent news organization” that publishes short (1000-word) journalistic articles “by academic experts for the general public . . . on the events, discoveries, and issues that matter today.” The Revealer, an online magazine, publishes articles by scholars, journalists, and freelance writers to provide the public “a wider lens . . . greater context . . . and more nuanced perspectives” to topics covered elsewhere.1 Some venues such as Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Quarterly directly appeal to insiders and those already familiar with the tradition; other outlets speak in a familiar style but are geared more toward academic audiences, whether students or scholars of religion (e.g., Keeping it 101, a podcast; Religion for Breakfast, a YouTube channel; The Public Scholars Project, an initiative which includes webinars and media training for scholars who want to engage in public scholarship).

Primary Audience. Click image to enlarge.

Traditional journalism represents a second mode in which scholarship is conveyed to the public. Whereas The Revealer and The Conversation publish work by professional academics writing for general audiences, other platforms produce what might be better described as religion journalism in which academics sometimes participate. Religion News Service and Religion Dispatches are good examples of these publishers.

If public scholarship is defined another way—as scholarship that occurs in public view, rather than scholarship intended for the general public—a number of other sites of production come into view. This sector consists primarily of professional academics writing for one another. One significant example is The Immanent Frame (TIF), which publishes articles about secularism by invitation-only. While TIF is online and available for anyone to read, the topics and style speak directly to academic audiences. The podcast-oriented Religious Studies Project is more casual in tone than TIF, but its target audience is also those interested in the academic study of religion. Similarly, sites like Maydan (Islamic studies) or Hazine (Central Asian studies, especially archival) speak to academic audiences in religious studies subfields. Some sites engage experimental modes of analysis, such as American Religion’s recent academic meditations on empty spaces.

Finally, there is a wide range of publications committed to theological or religious agendas, including some that might also fall into one of the above categories. Publishing outlets for religious audiences cover a spectrum of theological and spiritual orientations, including many for specific religious groups such as Christian denominations or Western Buddhist practitioners. Among the most inclusive of these sites is Patheos, which publishes a wide range of theologically oriented essays that speak to tradition-specific insiders as well as a spiritual-but-not-religious audience. Although some of its articles are authored by professional academics writing for general audiences, Patheos also publishes articles such as “Are Angels Real?” and “About Your Aura.” A site like Religion Dispatches, while journalistic in format, has frequently demonstrated editorial interests in atheism and agnosticism, hosting until recently a section titled “atheologies.”

Religious Alignments

Of the thirty-four sites surveyed, nineteen explicitly communicate their religious affiliation either through their magazine titles, mission statements, or mastheads. For example, Tikkun’s mission statement explicitly “uplifts Jewish, interfaith, and secular prophetic voices of hope that contribute to universal liberation.” America: The Jesuit Review of Faith and Culture is “the leading Catholic journal of opinion in the United States,” and Sapelo Square’s vision aims to “celebrate and analyze the experiences of Black Muslims in the United States.” Other sites are broadly Christian but denominationally unaffiliated, such as the conservative First Things, established by Lutheran-turned-Catholic cleric Richard John Neuhaus in 1989.

By contrast, sixteen sites show no clear identification with any specific group or teaching. Of these sites, several are broadly spiritual-but-not-religious, such as Killing the Buddha, which features “great writing from the margins of faith…by and for questioners since 2000.” (Its title is borrowed from a Zen maxim that challenges any reified notion of truth). Other sites generally embrace pluralism, provide a forum for interfaith dialogue, and engage with secularism. Patheos, for example, offers Progressive Christian, Evangelical, Pagan and nonreligious voices, with a menu of blogs representing most of the world’s major religious traditions. The Commons, a new online magazine edited by the Association of Public Religion and Intellectual Life, also features the “creative, critical, compassionate” visions and voices of artists and scholar-activists from a variety of traditions.2The Immanent Frame’s tagline is “Secularism, Religion, and the Public Sphere,” whereas Religion Dispatches aims to be “your secular, non-profit, award-winning source for best writing on critical and timely issues at the intersection of religion, politics and culture.”

Ideological Alignments

To help draw a picture of the ecosystem for public scholarship on religion, we studied sites to understand their ideological and political leanings. For the purposes of our analysis, we took “progressive” outlets to mean those that generally publish articles supporting racial justice, gender equality, LGBTQ+ inclusion, economic parity, immigrant rights, and anti-Islamophobia. By contrast, we understood “conservative” to signal anti-secular and anti-abortion perspectives and endorsements of traditional heteronormative family and society.

We initially included sites with clear conservative commitments but came to understand that while venues with robust scholarly engagement—understood as authorship by scholars, interviews with scholars or quotations from their scholarship, or discussion of scholarly publications or ideas—tended to lean left, conservative sites overall inclined towards far fewer scholarly engagements. In the end, we determined that including most of the conservative sites we were working with ultimately distorted the meaning of "public scholarship." We therefore removed all of them from our data set except for First Things, which projects learned opposition to secular culture, and Christianity Today, which includes a modest amount of academic material. For one example that illustrates the pattern we found, we removed Chronicles, which self-identifies as the Rockford Institute’s “paleoconservative” magazine, from our final analysis. It covers religious topics but shows little engagement with scholarship. These findings suggest to us mutually reinforcing suspicions between scholars of religion, who fall politically to the left of the general population, and conservative media, which is often antagonistic towards higher education and the professoriate.

Funding Models

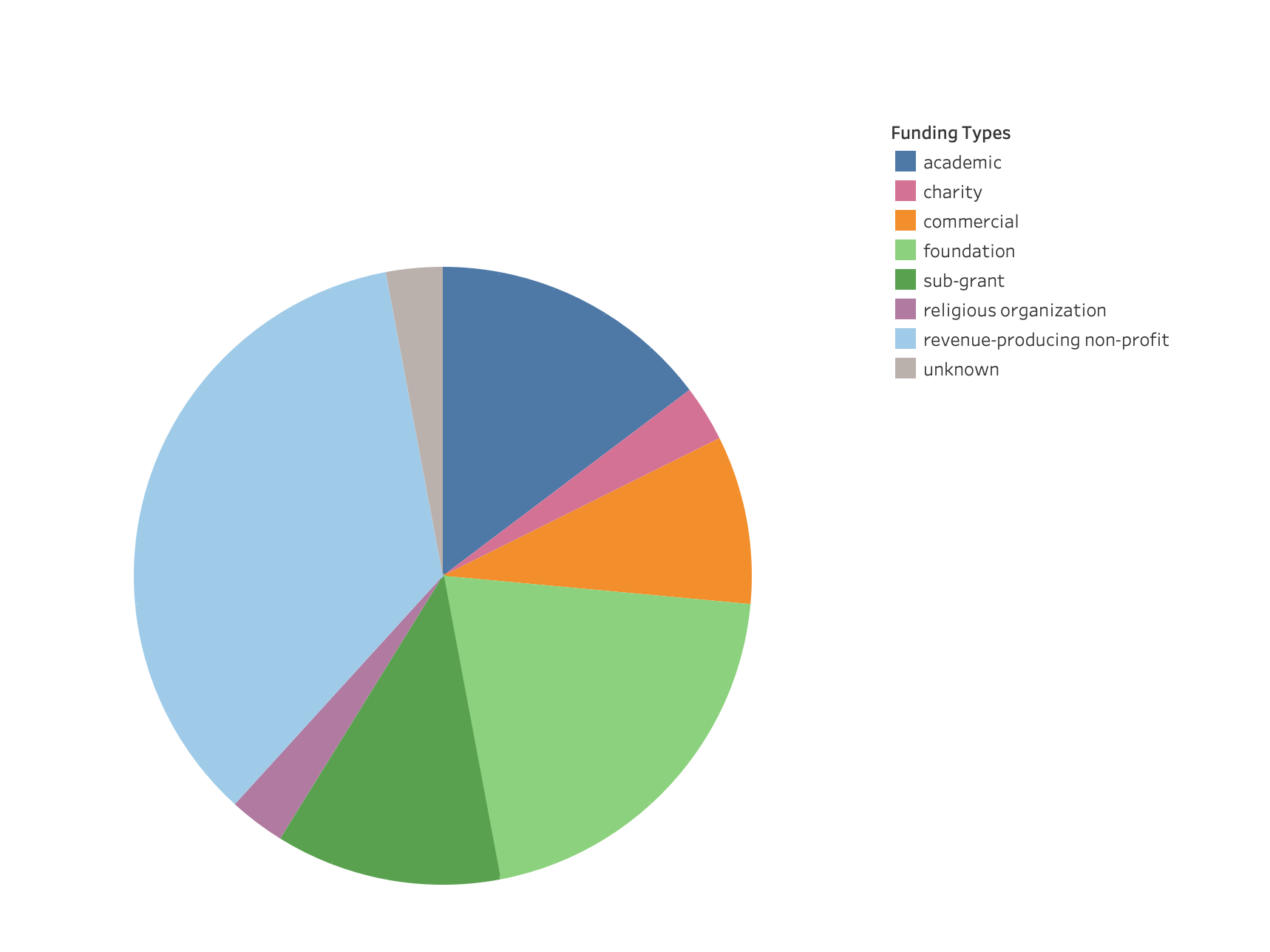

Publishing in any format requires resources, and so we therefore examined the funding models for the sites we studied. In many cases, sites are entirely transparent about their sources of support; others pointedly do not disclose the identity of their funders (Religion Dispatches stands out here). A clear set of patterns emerged alongside a few notable anomalies.

Charitable foundations play a major role in sustaining the ecosystem for public religion scholarship. Nine of the thirty-four publishing sites we surveyed receive major funding directly from foundations, and four others are funded through subgrants by parent entities which are themselves supported directly by foundations. Five sites receive primary support from an academic organization, including scholarly associations and university departments or centers. Only one receives the majority of its support from a religious organization (America Magazine/The Jesuit Review), and only one from voluntary donations (Hazine). Three major sites for public religion scholarship are commercial entities. Twitter falls in this category for the role it plays in public scholarly discourse, especially via skilled use of the tweet thread. Patheos is a for-profit website owned by BN Media’s Beliefnet.com that includes contributions from scholars.3 Sojourners appears to be sustained primarily through advertising and subscriptions.

The most common funding structure, employed by twelve of thirty-four sites, is the revenue-producing non-profit model, wherein a site or its direct funding entity with non-profit status generates revenue through the private donations, grant funding, and/or the sale of advertisements, subscriptions, or merchandise. Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Quarterly, for example, is published by the Lion’s Roar Foundation; the site sells subscriptions, advertising, and access to online courses. The executive director’s position at Lillith is supported by a foundation but it otherwise accepts donations and sells subscriptions.

Funding Sources. Click image to enlarge.

Recommendations

It is clear to us that recent efforts by foundations, scholarly societies, and individual scholars to expand the public reach of religion scholarship have borne fruit. Scholars of religion currently have many means of addressing public audiences, each with its own particular utility. Those who wish to address their academic peers about time-sensitive matters may find academic-oriented public scholarship sites to be a helpful alternative to peer-reviewed publication. Some may feel a vocational calling to promote religious literacy among the general public; a different set of sites are helpful for those purposes. Those who feel stifled by conventional writing formulas may find that public scholarship venues offer new opportunities for greater creativity. The digital landscape for public scholarship on religion is robust and varied. We offer the following recommendations for enhancing the use and recognition of those sites which are already available and addressing gaps that we identified.

- Development of Teaching Resources. The public sites we surveyed can often be pedagogically helpful, especially at the introductory level. The podcast Keeping it 101 is very classroom-friendly, and blog-style sites like The Conversation and Religion Dispatches can provide students accessible entry points for substantive discussion about the role of religion in the public sphere. Introductory students are more likely to be engaged by this kind of timely, relevant, unfiltered, jargon-free, and question-driven writing than by the typical textbook prose, which provides foundational information but whose currency or relevance may not be obvious to them. A useful addition to the digital landscape, therefore, may be curated collections of public scholarship specifically written or selected for undergraduate classroom use.

- Attend to Method, Theory, and History. Two gaps stood out to us. First, topics like methodology and discipline-specific theory do not often appear in pieces written for the general public. Current political disputes over Critical Race Theory illustrates both that more abstract questions of the discipline have public relevance and that responsible discussion of these issues can inform public debate. Second, public scholarship tends overall to be presentist in orientation, and those who work on historical materials surely have things to say of interest to both students and the public that would not easily find a place on a site like Religion Dispatches.

- Recognize Work at the Leading Edge. Our survey of the landscape leads us also to suggest that the AAR—perhaps through its Committee for the Public Understanding of Religion—annually recognize an academy member’s public work on the basis of its relevance to or impact on the public understanding of religion. The AAR’s Marty Award ostensibly achieves this end, but the award has historically recognized senior academics based on a body of traditional scholarship. The AAR’s annual journalism awards give visibility to important achievements in fostering public understanding but they are reserved for professional journalists. Neither award either recognizes junior or untenured scholars who tend to contribute to digital outlets more than their senior colleagues and who may also benefit professionally from the recognition early in their careers.

- Elevate Public Scholarship. Such formal measures would help to move the needle on what constitutes meaningful scholarly work in our field. There will always be a need for rigorously peer-reviewed books, articles and chapter contributions about religion, and these will continue to define the evaluative criteria for promotion and tenure review committees. At the same time, however, promotion and tenure committees could be encouraged to consider the quality and impact of public scholarship in assessing a candidate’s reputation and influence in the field. The AAR’s 2019 Board Resolution on the evaluation of scholarship for promotion and tenure offers a good starting point. Publishing an op-ed in a major daily newspaper, for example, or writing as a scholar-activist for popular online sites carries enormous potential for societal impact. Recent controversies involving public intellectuals Cornel West and Nikole Hannah-Jones seem to indicate that such activities may actually imperil a candidate’s tenure case. The insulation of the academy from the public square is self-defeating for our profession. In the UK system, by contrast, this kind of para-professorial activity, often referred to as “knowledge exchange,” may indeed contribute to scholarly reputation in ways that institutions recognize. Especially in a milieu of budgetary cuts and departmental shutdowns in the humanities, we need to collectively strategize about new ways to demonstrate the social and intellectual value of both peer-reviewed and public scholarship and to advocate for and support public intellectuals in our discipline.

1 N.B. The Conversation and The Revealer are both funded by The Henry Luce Foundation which also sponsored our survey.

2 Disclaimer: co-author Pamela D. Winfield is an associate editor at The Commons.

3 BN Media LLC is an offshoot of Rupert Murdock’s conservative media empire and Beliefnet.com has ties to evangelical Christianity, but Patheos appears separately from them as its own website. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/beliefnet-announces-acquisition-of-patheos-300323027.html