Teaching the Paranormal and the Occult: Editor’s Introduction

Walk into a classroom early and you might overhear students talking about such television shows as The Walking Dead, Ghosthunters, or Haunted Case Files; or the latest horror film like Ouija: Origin of Evil. Such paranormal pop culture is so prevalent these days that there is a website whose mission is “dedicated to covering all of paranormal culture in mass media.” While the website does not endorse claims about the paranormal, it does reflect the widespread interest in the paranormal among the population. Personally, I love the films that deal with ghosts and demons, as do many of my students. They are intrigued, if not a little bit spooked, by the genre. They want to believe that there are mystical experiences and forces that transcend the routine in everyday life. I share their interest.

The appeal of these media to our students should not be surprising given that several polls over the years have shown that quite a few Americans, especially college-aged students, have some belief in or even experience of the paranormal. A Gallup poll (2005) indicated that three in four Americans profess at least one belief in the paranormal, such as extrasensory perception (ESP), the existence of haunted houses, or the presence of ghosts. A Pew Research Survey (2009) found that 49% of Americans said they had a religious or mystical experience, defined as a “moment of sudden religious insight or awakening.” These types of experiences are common among the “religious unaffiliated” (i.e., those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” and say that religion is at least somewhat important in their lives), among whom 51% have had a religious or mystical experience. Moreover, 29% of all respondents said they had felt in touch with someone who had died. A 2013 Harris Poll, found that 42% of adults say they believe in ghosts, 36% say they believe in UFOs, and 29% say they believe in astrology.

Student interest in various forms of spiritual experience, whether traditional or paranormal, is consistent with the findings of the UCLA study among college students, “Spirituality in Higher Education.” The study found that although religious engagement declines somewhat during college, students’ spiritual interests and qualities, such as actively seeking answers to life’s big questions and the development of a global worldview that transcends ethnocentrism and egocentrism, grow substantially—especially in classrooms that expose students to diverse cultures and worldviews and encourage self-reflection and meditation. The authors of the essays in this edition of Spotlight on Teaching contend that these spiritual qualities can be and have been developed through engaging students in the study of the paranormal and the occult.

Most of the authors emphasize beginning with the lived realities of students both in terms of popular culture and also in relationship to the social locations in which they are enmeshed. Jack Hunter suggests that the strong connections between the paranormal and popular culture, evident in films, books, etc., are present in many of our students own lived experiences. They can relate to them in significant ways and may be an avenue for a stronger connection to the study of religion generally. Richard Callahan agrees: “all around us there is widespread belief and practice and representation of the supernatural and strong student interest in this material.” In his “Haunting and Healing” class, he begins with what is familiar to students and then draws their attention to local ghost stories to engage them in dialogue and to get them comfortable with the ambiguity and ambivalence inherent those stories; characteristics which Darryl Caterine argues are also endemic to the term and study of “religion.”

The challenge posed by beginning with students’ interest in the paranormal is to get them to think more critically and more deeply about the subject matter. The authors herein engage in a variety of pedagogical practices. Madeleine Castro uses reflective exercises and moments to get students to the point of “critical being,” a state that involves their whole selves, not just their minds, and promotes “the cultivation of a sensitive and respectful approach to different perspectives.” Such fairmindedness is also the aim of Joseph Laycock, who uses some traditional pedagogical methods, such as the semester-long research paper, to help his students find the “balance between the hermeneutics of respect and the hermeneutics of suspicion,” which he notes is a problem for all who engage in the study of religion. When looking at spirit possession and demons in his course, he can move his students beyond religious literacy to engage the questions of meaning that religious and paranormal phenomena raise.

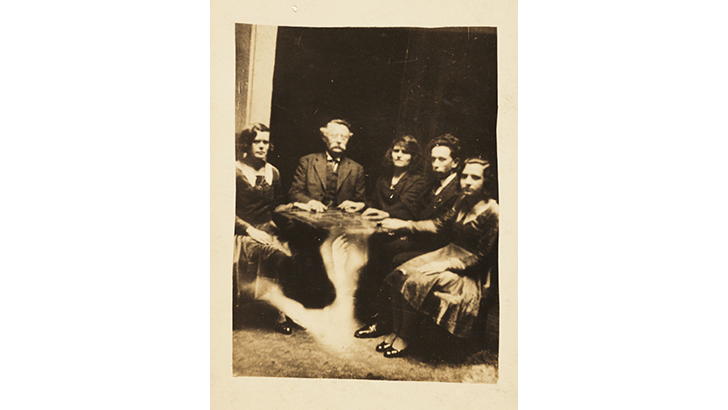

Charles Emmons gets his students to understand the interconnections between scientific and “intuitive” ways of knowing (broadly defined) by incorporating some of the practices associated with the paranormal: ESP games, healing practices, and visits by spiritual mediums or psychic readings. In their journaling, he invites students to recognize the social construction of all knowledge. “Doing experiential, intuitive exercises in the classroom acknowledges that there are other ways of knowing besides mainstream science.” Caterine uses a medium and the séance as an experiential way to get students to think through their own understandings of these realities. The experience engages them intellectually and emotionally as they explore what happened.

Of course, such investigations of paranormal beliefs and practices carry some risk, especially for those students whose religious traditions view such beliefs negatively. Whether in a classroom with evangelical students in West Texas (Laycock) or in a class with predominantly Catholic students in Central New York (Caterine), faculty should be sensitive to the religious frameworks students bring with them as part of their lived reality. However, in their experience the exploration of the paranormal not only broadens students’ understandings of the complexities of religious and spiritual reality, it also provides opportunity for them to discover more deeply their own religious commitments. Hunter contends that by bringing their own experiences with the paranormal into the religious studies classroom, the teacher can create a safe environment for a fuller conceptual exploration of these phenomena and experiences, and may contribute to their own spiritual development. The example he provides is the way in which students’ explorations of questions related to UFOs enabled them to explore their understandings of the nature of God, thus improving their critical thinking capabilities. Likewise, Caterine remarks that one of the results of teaching about the occult is that it opens students to a renewed interest in their own traditions, hence creating an opening to a growth in their own spirituality.

One final theme in these essays is the sense that the study of the paranormal and the occult may be the future of the study of religion. For Laycock, the study of spirit possession and demons enables students to get in touch with the theory and method of religious studies. It gets them to wrestle with the ambiguity of the questions these phenomena raise. Callahan argues that the study of paranormal is underrepresented in his field of American religions: “I see it as a possible method of religious studies for a post-secular age, intent not on debunking but on reflexively exploring ‘reparative’ or creatively constructive readings of cultural phenomena.” Caterine contends that the paranormal and the occult border between traditional study of religion and new scientific ways of looking at the world. It provides an avenue for students and professors alike to “pioneer new intellectual ground in the interstices of institutionalized religion and science,” like what occurred with early occultists. All the authors agree that there are no answers to the questions raised by these phenomena, but that is the allure: wrestling with questions that perhaps have no answers but lead all to grapple intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually. It is, they claim, the next step in the evolution in the field. Given the widespread interest in the paranormal and the occult, they may be right.

Resources

Astin, Alexander W., Helen S. Astin, and Jennifer A. Lindholm. 2011. Cultivating the Spirit: How College Can Enhance Students’ Inner Lives. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fred Glennon is professor and chair of the Department of Religious Studies at Le Moyne College. He teaches a variety of courses in religious ethics, including Comparative Religious Ethics and Social Concerns (in classroom and online formats). His research and teaching focuses on religious ethics and social justice. He also writes and publishes in the area of the scholarship of teaching and learning, with a number of publications in Teaching Theology and Religion. He is coauthor of Introduction to the Study of Religion (Orbis Books, 2012), now in its second edition.

Fred Glennon is professor and chair of the Department of Religious Studies at Le Moyne College. He teaches a variety of courses in religious ethics, including Comparative Religious Ethics and Social Concerns (in classroom and online formats). His research and teaching focuses on religious ethics and social justice. He also writes and publishes in the area of the scholarship of teaching and learning, with a number of publications in Teaching Theology and Religion. He is coauthor of Introduction to the Study of Religion (Orbis Books, 2012), now in its second edition.