Experiencing Occult/Paranormal/Spiritual Phenomena in the Classroom

Experience as a Way of Knowing

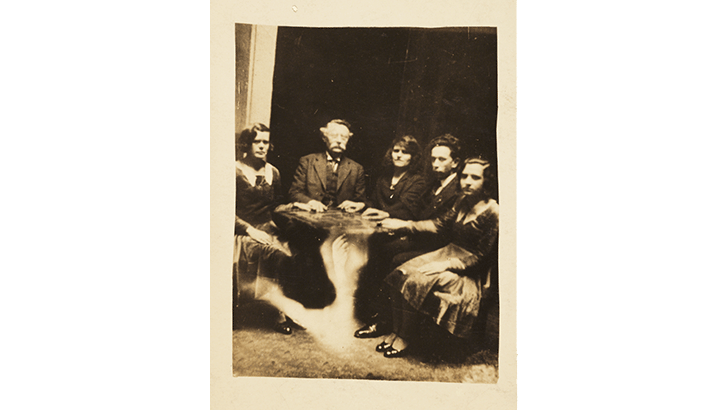

In both my “Sociology of Religion” class and my “Science, Knowledge, and the New Age” class, there are treatments of such occult, paranormal, and/or spiritual topics as spirit mediumship, ESP, apparitions, and spiritual healing. Especially in the latter class, the emphasis is on the sociology of knowledge, or ways of knowing. The main course objective is to understand both scientific and “intuitive” (broadly defined) ways of knowing and to compare and to see interconnections between the two.

To this end, I have students meditate almost daily and write about their experiences in a journal which also includes other intuitive exercises such as ESP games, hands-on healing, and spirit mediumship (or psychic reading), both inside and outside of class. We begin with simple forms of meditation and mindfulness, working our way from ten minutes a day to twenty or more, and varying the instructions and options throughout the course. This is like “swinging the leaded bat” in baseball and opens them up to other forms of intuition later on. Eventually there are other classroom exercises in ESP (such as psychometry, trying to get information psychically from objects placed in envelopes by their classmates), hands-on healing with individuals or groups of classmates, and giving psychic/spiritual messages to classmates in a circle, after demonstrations by a healer or medium.

This always “works” in that students become engaged and gradually dare to share their experiences and feelings. These feelings range from surprise (even astonishment sometimes) at informational accuracy or healing results, to skeptical evaluations or frustration at having trouble meditating, for example. “I could really feel the heat around my knee.” “I can’t believe the details she told me about when I was in New York.” “I think I’m just making stuff up; nothing was accurate.” “Meditating is just making me more irritated.”

We also compare their experiences to the content of video clips (such as Dr. Herbert Benson’s Harvard studies of Tibetan monks meditating, turning the cold water in the towels on their backs into steam with their elevated body heat) and class readings about scientific attempts to study spiritual healers and spirit mediums.

Journal entries generally show a progression to greater comfort with meditating, for example, although some students, maybe 10–20%, make little progress or say that they just can’t do it or can’t think of ways to reflect very much on their experiences. I emphasize that they can’t “do it wrong,” and that the more trouble they have meditating (due to stress, etc.), the more likely they are to benefit from it. I also give them articles about studies of such benefits. Occasionally I get communications from students years later about how taking this class saved them from dropping out of college due to stress-reduction from meditation or other healing benefits. One student said that she had been healed in class one day permanently of a chronic infection and was inspired to open a health-food store and spa with a partner.

How Students Learn

Students are used to academic or scientific ways of learning, but how are they to understand intuition without practicing it? There is a great deal of discussion in higher education about student engagement in learning, but this is mostly within the usual academic frame. It involves writing and communicating orally in class, and doing creative research in the library or in gathering original data. There are growing exceptions to this limited focus. For example, I know of some other classes in which students learn some yoga (in someone else’s sociology class) or do some meditating (in a religious studies class). Most students are hungry for complementary learning methods. This includes not only my particular experiential method described here, but also service learning, study abroad, and internships. Ever since the 1970s when I was the Gettysburg College campus coordinator for internships in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, I have tried to get students to integrate academic and experiential learning, instead of divorcing academics from the “real world.”

One issue with my method is that some students might object to the intuitive exercises on religious grounds, for example. This is why I have stated for the past fifteen years in “Science, Knowledge and the New Age” that I will give anyone an alternate assignment if this is the case. Not a single person has ever asked for an alternative. One reason for this is probably that Gettysburg College has very few students with strongly conservative religious views. At another college in the 1970s, I was told by a sociology professor with very liberal views that one of his students said, “The Devil [was] lurking in the classroom.”

I have also seen resistance to spiritual aspects of yoga from local residents in a yoga class I have attended in the town of Gettysburg. The highly secular context of Gettysburg College (never mind that it is loosely affiliated as a Lutheran College) means that opposition is more likely to come on scientific grounds. I have heard some derision from faculty over the years about my interest in the sociology of the paranormal but very little if any from students, who are more likely to be curious about it. One professor did tell one of my students recently, “Oh, Professor Emmons is doing that in class? Well, he believes in ESP, you know.” My response to students about such things is that I do not believe in belief; as a (social) scientist I am interested in experience and other forms of evidence.

How Do We Know What We Think We Know?

Sociology is by nature a subversive exercise. Taken seriously, it questions not just authority but everything that is taken for granted, including how we know anything. I tell my students, “The only thing I know is that I don’t know anything for sure.” This is a paraphrase of Socrates, who claimed to know nothing, but I say that I might actually know something and not realize it. My favorite subversive topic is the sociology of knowledge. One view of this is that all knowledge has a social origin or context and that scientists and academics in general have a privileged way of knowledge-creation based on objectivity. I say that we must look at ourselves in the mirror and make no exceptions to the principle that all of our knowledge is socially (and individually) constructed. Ultimately, objectivity is an ideal in science, but it is not a completely attainable reality as long as human beings with interests and social origins are involved.

Doing experiential, intuitive exercises in the classroom acknowledges that there are other ways of knowing besides mainstream science. And there is evidence that scientists rely on their own experience, just as the rest of us do, especially when taboo forms of knowledge or “paranormal” (occult) phenomena are concerned. As Andrew M. Greeley said, “The paranormal is normal.” In other words, most people have so-called paranormal experiences. It is just no good to ignore such experiences and ways of knowing on the grounds that they are unscientific or “pseudoscientific”.

At the very least, we need to study occult/paranormal/spiritual phenomena because they are part of human experience. Studying them from “objective” distance can be useful but is neither entirely satisfying nor completely effective. Sociologists and anthropologists employ many research methods, among which are ethnographic interviewing and participant observation, both designed to get closer to the experiences of the people they are studying.

Conclusion

In our postmodern world, scholars talk about tearing down the barriers to understanding caused by “othering” people of different cultural and demographic categories from us. Too rigid a differentiation between scientific thinking and magical or spiritual thinking heightens barriers between ways of knowing and creates distance from understanding the beliefs and experiences of others.

With the experiential, intuitive exercises in “Science, Knowledge and the New Age,” students are learning to share the perspectives of those who experience paranormal or spiritual phenomena, including themselves. But they also learn to stand back and reexamine their experiential evidence from scientific perspectives as well, perhaps integrating the scientific with the intuitive.

Resources

Aronowitz, Stanley. 1988. Science as Power: Discourse and ideology in Modern Society. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Greeley, Andrew M. 1975. The Sociology of the Paranormal. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hunter, Jack. 2015. Strange Dimensions. Lulu.com.

Mannheim, Karl. 1954. Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Mayer, Elizabeth Lloyd. 2008. Extraordinary Knowing: Science, Skepticism, and the Inexplicable Powers of the Human Mind. New York: Bantam.

McClenon, James. 1994. Wondrous Events: Foundations of Religious Belief. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Charles Emmons is a professor of sociology at Gettysburg College, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. He has published books with Penelope Emmons on spirit mediumship, (Guided by Spirit: A Journey into the Mind of a Medium, Writers Club Press, 2003 and second edition forthcoming 2017), and on scientific studies of consciousness (Science and Spirit: Exploring the Limits of Consciousness, iUniverse, 2012). He is currently writing an ethnography about scientific, paranormal, and spiritual approaches to integrative medicine by practitioners and clients.

Charles Emmons is a professor of sociology at Gettysburg College, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. He has published books with Penelope Emmons on spirit mediumship, (Guided by Spirit: A Journey into the Mind of a Medium, Writers Club Press, 2003 and second edition forthcoming 2017), and on scientific studies of consciousness (Science and Spirit: Exploring the Limits of Consciousness, iUniverse, 2012). He is currently writing an ethnography about scientific, paranormal, and spiritual approaches to integrative medicine by practitioners and clients.