Teaching and Learning from the Uncertainties of Occult Phenomena

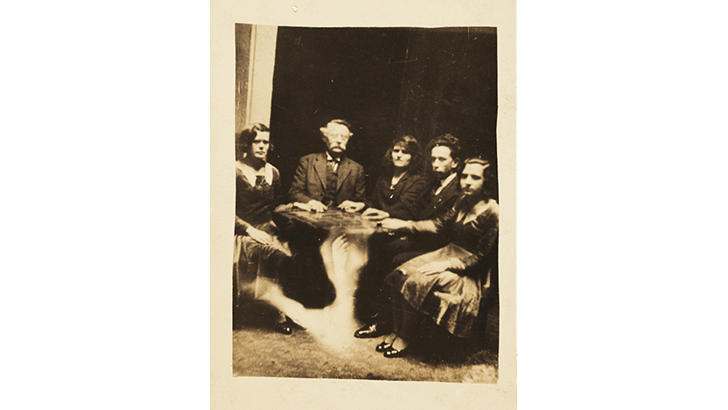

The Séance as a Teaching Event

There are many ways one could frame a course in American occultism. I structure my “Occult in America” seminar around a certain set of highly bizarre and contested phenomena that have set in motion a number of cultural and religious movements variously labeled as “harmonial,” metaphysical,” or “occult”—and that continue to elicit both fascination and denouncement today. These phenomena include the reports of spontaneous healings and parapsychological activity (e.g., telepathy and clairvoyance) that circulated in 18th century Europe and 19th century America with the advent of mesmerism. They also include alleged demonstrations of the survival of consciousness after death: accounts of mediumship in the 19th century, and modern research on near death experiences over a century later. By the end of my class, students will have learned the histories of mesmerism, Spiritualism, and Theosophy in 19th America, and they will have explored at least one 20th century occult religion. But gaining such historical knowledge and perspective is not the primary goal I have in mind for my students in this course. More than anything else, I want to provide them with exposure to some of what Charles Fort called the “damned facts” lying at the heart of modern occultism—situations that are not supposed to happen, but seem to anyway—and to accompany them through the complexity of analyzing and narrating what they might be. Depending on how they end up interpreting the data, the “Occult in America” might be for many students a fifteen-week immersion into the miraculous and/or paranormal dimension of human experience. Or it might prove to be an introduction to the history of fraud and pseudoscience. Or it might be a foray into a social and epistemological space charged with the valence of deviance and taboo. But whatever they might ultimately choose to call it, by the end of the semester, the “Occult in America” course will have introduced students to contingency and fluidity of interpretation itself, for to dwell on the occult is to study the tricksterish nature of knowledge.

I did not set out to teach American occultism with this goal of academic self-reflexivity so explicitly in mind. It was only seven years ago, after giving up on the search for a good documentary on modern mediumship, that I decided to invite a medium whom I had met during ethnographic research into my classroom, both to discuss the history of American Spiritualism and to deliver readings. The effect was electric, and ever since then attendance at a séance has been a strongly recommended, though optional, part of the course. It is important that this event does not happen too early in the semester; we need time to explore a few methodological lenses through which the nature of mediumship might be understood. Derived from readings and lectures on the histories of Spiritualism, psychical research, and stage magic, these consider the séance respectively as a demonstration of thaumaturgy, telepathy, and/or performance art. The point is that none of these frameworks have ever succeeded in fixing the meaning of mediumship. What was true in the 19th century is just as true today: the séance is an underdetermined phenomenon, a fact-in-the-process-of-becoming, a highly contested performance that elicits everything from accusations of deception to on-the-spot mystical experiences. But it is one thing for the students to read about this, or hear it said in lecture. It is an entirely different thing for them to interact with a medium in real time, or watch others interact with her, and then narrate what, exactly, just transpired. It is at this point that the class crosses over the line from learning about the occult to writing its meaning into being.

The fact that the séance is an optional component of the seminar has not seemed to detract from its power to enliven the subject matter of the course for all students enrolled. The classes held after the medium’s visit evolve into open-ended discussion, for those who attended, to make sense of their experience. For those who have not, it is an opportunity to witness the powerful effects this occult ritual typically has on their peers, and to field their own doubts and questions. There has never been a unified, consensual explanation of what, exactly, the medium did when she brought through readings—or how those in the audience helped create the experience. These conversations are lively and charged. The nature of the séance coaxes us out of whatever protective shell, intellectual or personal, to which we are accustomed; both the students and I put our interpretive cards on the table, and together actually elaborate on the medium’s messages through our own reflections, critiques, and self-disclosures. In these discussions, the undetermined status of the occult is no longer a philosophical abstraction, but a dimension of our efforts to narrate religion. Students thus develop an experiential understanding of why the “occult” is so notoriously hard to pin down, and why it circulates in modern society as a term fraught with so much controversy. This realization not only adds a noticeable depth to our subsequent explorations of occultism, but exposes in a powerful way the complexities of studying and writing about religion in an academic setting.

The Occult Art of Writing about the Occult

My continued choice to structure the occult seminar around indeterminate paranormal phenomena reflects my own scholarly approach to and experience with the material, which as I have already mentioned is rooted in ethnographic research. Beginning in 2007, I spent three consecutive summers immersing myself in various occult-related gatherings across the United States, where mediums delivered messages from my deceased relatives, alien abductees recounted to me their otherworldly journeys, and dowsers passed on their arts of finding underground water or distant objects with everyday household items. I had already conducted ethnography as a graduate student years earlier in a very different corner of the American religious landscape, among predominantly Latino Catholics. In that context, I met people who found in their faith tradition a powerful set of resources to articulate religio-cultural identities. Setting off to document occult subcultures, I assumed that this project would entail using the same basic set of skills I had used before: composing thick descriptions of rituals and sacred spaces, recording and transcribing interviews, and finally contextualizing the data into extant historical and anthropological literature. But this did not prove to be the case. First, in sharp contrast to the subject of my earlier research, one of the signature features of modern occultism is its decidedly liminal nature. It was not simply that the experiences I recorded and sometimes witnessed went beyond (“para-”) the perceived limits of the everyday world; it was also true that the gatherings I attended were charged with a ludic and sometimes carnivalesque air. I could never be sure when I was part of an earnest exploration into some aspect of metaphysical reality, or when I was participating in a kind of collective, improvisational performance art. How was the project of ethnography—a mode of scholarship premised on the goal of “making the strange familiar”—equipped to represent such a tricksterish strand in modern culture? What I was encountering was strange, and as a writer I needed to keep it that way, lest I distort the subject matter to the point of misrepresentation.

Second and even more saliently, I came to the conclusion that at least in the North American context, there is no such thing as an occult “tradition” to record, if by this term, we mean a set canon of sacred texts, an identifiable genealogy of interpretation, or, with a few exceptions, stable communities of practitioners. Even if I might succeed, as a writer, in producing thick descriptions of ambiguity (both in relation to the phenomena themselves, and the communities coalescing around them), it was not at all clear to me which body of extant literature on the “occult”—or was it “paranormal”? or “pseudoscientific”? or “supernatural”? or “esoteric”?—these descriptions belonged. The people with whom I interacted and from whom I learned could come to no consensus among themselves on the nature of the phenomena at hand: hence, for example, the currency of the term “unidentified flying object.” The many scholarly works I read on the occult were helpful in illuminating some aspect of what I had encountered during research, but no one scholar or study exhausted its meaning entirely. What I was trying to describe and analyze was very much a work of grassroots bricolage, an attempt to create a religious tradition ex nihilo in which every interpreter had as much, or as little, authority as the next. The ambiguity of the term “occult” struck me as a powerful analog for the concept of “religion,” and the efforts of my subjects to create a tradition from the ground up an analog for our scholarly efforts to elaborate upon a concept for which there is ultimately no stable meaning. The occult thus became a mirror in which to ponder the inherently poetic dimension of scholarship. It would not be for several more years that I would find a way of replicating this realization for and with my students by inviting a medium to bring through “messages from the dead” into the classroom—and asking the students to narrate their experience.

An Invitation to Live with the Questions

In my seminar, we analyze the emergence of American occultism as one attempt to build bridges between the ailing liberal Protestantism of the 19th century (ala Ralph Waldo Emerson’s description of Unitarianism as “corpse cold rationalism”), and various scientific discoveries of the day, particularly those pertaining to the nature of consciousness. Within this framework, my students tend to take one of two major insights from the course. Among non-science majors, many students incorporate insights gleaned from the occult into their pre-existent religious understandings of the world, which at my college is mostly Roman Catholicism. Science majors, in contrast, typically express surprise and enthusiasm that there are modes of religious inquiry outside the domain of institutions, and that the study of the natural world can enhance the search for meaning. In either case, however, it is the open-ended, underdetermined nature of the damned facts of occultism that opens for them new and exciting vistas of thought.

For students drawn to the religious implications of occultism, the course seems to open an intellectual space in which the mystical dimension of Christianity takes on a fresh allure. This might sound surprising since occultism in general, and mediumship in particular, are denounced in many Christian denominations. But given occultism’s fascination in exploring interiority and the frontiers of the human psyche, the fit with contemplation suggests itself. My Catholic students appreciate the seminar’s approach to extraordinary experiences and phenomena as open questions that they can explore and debate, rather than predetermined facts they are obliged to accept. Many students who had long abandoned vital engagement with religious questions typically report a renewed interest in their own traditions, as well as a curiosity to learn about new faiths.

For students coming out of science backgrounds, the class serves as an introduction to the history of science, which is not a major offered at my college. Most of them have never had the opportunity to step back from their disciplines to ask broader questions about the evolution of western science against the background of a Christian culture. Particularly when we discuss aspects of the occult in the context of neuroscience or integrative medicine, many of these students reclaim the sense of wonder that animated them to pursue the natural sciences to begin with, but that had become lost at some point in the demands and pressures of their studies. They, too, appreciate the fact that there are open questions left to explore, that studying science entails much more than simply “learning the answers.”

I have no way of telling how my seminar would play differently in another part of the country, or at another school, but my students—today, members of the spiritually seeking Millennial generation—are especially open to pioneering new intellectual ground in the interstices of institutionalized religion and science, finding many of their own questions reflected in the speculations of earlier American occultists. The nature of the material covered in our seminar is bound to raise more questions than it is to deliver any certitudes, but this is precisely what they seem grateful to discover. As a teacher in the humanities, I can think of no better way to catalyze their excitement for learning than to expose them to questions that I have yet to answer myself.

Resources

Clifford, James, ed. 1986. Writing Culture: the Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hyde, Lewis. 2010. Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kripal, Jeffrey. 2010. Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McClenon, James. 1994. Wondrous Events: Foundations of Religious Belief. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Taussig, Michael. 2006. “Viscerality, Faith, and Skepticism: Another Theory of Magic.” In Walter Benjamin’s Grave (121–156). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Darryl Caterine is a professor of American religions in the Department of Religious Studies at Le Moyne College, in Syracuse, New York. He has published a full-length book on American occultism, Haunted Ground: Journeys through a Paranormal America (Praeger, 2011), as well as several essays analyzing select occult movements in the modern age. He is currently editing a collection of essays by various scholars on the paranormal and popular culture.

Darryl Caterine is a professor of American religions in the Department of Religious Studies at Le Moyne College, in Syracuse, New York. He has published a full-length book on American occultism, Haunted Ground: Journeys through a Paranormal America (Praeger, 2011), as well as several essays analyzing select occult movements in the modern age. He is currently editing a collection of essays by various scholars on the paranormal and popular culture.