A Proven Practice: Reflections on Teaching Online (Part II)

This is a the second post in called A Proven Practice, an initiative of AAR’s Teaching Religion Program Unit and Committee on Teaching and Learning to collect and share faculty pedagogical techniques that have shown promise in the transition to online learning as a result of COVID-19. Do you have a successful technique to share with colleagues? Submit it for publication. Read Part I of A Proven Practice.

Submissions signed as received.

Synthesizing Student Discussion Posts to Facilitate Critical Reflection

I teach World Religions at a medium-sized regional public university in a writing-intensive upper-level undergraduate course taken mostly by non-majors. Each week I assign chapters from our textbook as well as short articles and documentaries (these often serving as a way of complicating the textbook’s presentation of a given tradition). To guide student engagement with the assigned material, I give students two discussion prompts. They are required to write an original post and a response post totaling approximately 600 words. I identify which of the two prompts generate the most posts and compose a longer post of 1200–1500 words in which I quote from each of the students who posted on that prompt (making sure to write students’ names in bold), comment on the developing discussion, and offer additional resources (e.g., documentaries, music, further readings, etc.). Students are not required to respond to this longer post, but I have heard back from students anecdotally that they appreciate the synthesis because often times it is “annoying” to sift through 20–30 original posts from their classmates.

This practice impacts student learning on multiple levels. First, it forces students to think more synthetically about the subject matter we cover that week by incorporating multiple points of view in a single place. This may sound simple, but the visual difference is striking. When I respond to each student individually, there are 25 different conversations taking place. When I respond to 15 students all at once, I feel it more closely approximates the type of work that we do in a conventional classroom during a seminar. These longer posts are more engaging to write, and honestly, they do not take me longer than responding to the same number of students individually. One struggle of the online environment is building community for a group of people who most likely will never meet in person, and this practice is my way of attempting to address that issue. In providing a longer post for students to read, my intention is that they take a bit longer to think about that week’s material. My sense from talking with students about their experience taking online courses is that they read posts from the instructor with a bit more attention than their peers.

The asynchronous discussion thread is nearly ubiquitous in online courses, so this practice can be easily adapted for other settings. To scale up for larger classes (50+ students), I would write two or three longer posts, dividing students up according to which prompts they respond to or even when they post (there are always those who post first thing Monday morning, and others who wait until much later). My course has 25 students, so I can address the majority of my students through one longer post. With smaller courses, I would require students to respond directly to the longer post at mid-week, allowing that to serve as the focus for discussion for the rest of the week. Regardless of the course size, instructors could create small groups of 4–5 students and then ask each group to respond to posts from the first part of the week. Either way, when I take the time to synthesize what students are generating, it produces opportunities for students to reflect more critically on the subject matter. On my end, it also helps fend off the complacency that I feel can come with teaching online; it is easy to fall into the habit of sending perfunctory responses (i.e., “good work this week!”), but I have found that this rarely yields more integrated discussion. I feel more excited about my online classes when I employ this practice, and that enthusiasm carries into the rest of my interactions with students.

Patrick J. D’Silva, PhD

Lecturer, Department of Philosophy

University of Colorado, Colorado Springs

pdsilva@uccs.edu

Book Circles for Religious Studies Courses

As a self-study researcher, I always aim to develop improvement-aimed pedagogy for my teaching practice. I regularly teach online courses in philosophy, religion, and education for undergraduates at several public universities. In this article, I specifically focus on the book circles project that I incorporate into my Religions of the World course, which I teach online for Montclair State University, St. Johns University, and the University of South Carolina, Aiken. I utilize Canvas at Montclair State University and St. Johns University, whereas I use Blackboard at the University of South Carolina, Aiken. While some undergraduate students are religious studies majors or minors, many are not.

During the first week of class, I discuss religious literacy and why it is important. Religious literacy involves the basic comprehension of world religions. Students should understand how ritualistic practices, often endorsed by religious scriptures, shape the epistemological frameworks of faith-based believers. I ask students to pay attention to how they develop religious literacy throughout the semester.

The pedagogical point of the book circles is to provide students with a self-paced opportunity to delve deep into the study of a particular religion to develop religious literacy. The Religions of the World course provides an introduction to world religions, but does not move into depth.

I ask students to select a book of their choice from a list of book circle book choices on the syllabus during the first week of the semester. Students inform me of their book choice. Following this, students acquire the book and develop a self-paced reading schedule for the semester. Each week I send my students a course update email that includes a reminder to work on their book circle project. Each student is placed in a group based on the book that they read for the sole purpose of the book circles discussion forum at the end of the semester. In the past, I invited students to discuss their book in groups online throughout the entire semester through discussion forums that I set up solely for their group. However, this did not work well for my online courses because students often felt pressured to keep up with their peers. Since the book circles project is designed to be self-paced, I decided not to have students meet in weekly groups. Instead, at the end of the semester, I host a book circles discussion forum asynchronously online. Students gather together online to discuss their books. We discuss three books the first week and two to three books the second week.

The discussion has two main parts. First, students answer a series of discussion prompts about the selected book. Here are the discussion prompts:

- What is the author’s main problem?

- What theoretical framework or research method does the author use to examine the problem?

- What conclusions did the author reach?

- Did the book have an impact on you?

- What did you learn?

- Is there anything in particular that you would like to share about the book?

Second, students engage with one another on the discussion forum about the selected book. I use a Philosophy Session Guided Observation rubric, published by the Institute for the Advancement of Philosophy for Children, to grade the discussions.

Students frequently express how much they enjoyed the project because it gives them a chance to focus on a text that they want to study. Aside from religious literacy, I teach students about Orientalism in my religious studies courses. Edward Said coins the term Orientalism as he points to the way the West often misrepresents the East, which furthers misconceptions of religion and culture. Students convey that they gain religious literacy and confront their Orientalized stances as they read the book of their choice. Here are some suggested books for the book circles in the Religions of the World course:

- Clatterbuck, Mark. Crow Jesus: Personal stories of Native Religious Belonging. Oklahoma: Oklahoma University Press, 2017.

- Curtis, Edward E. The Practice of Islam in America: An Introduction. New York: NYU Press, 2017.

- Hoff, Benjamin. The Tao of Pooh. Boston, Massachusetts: Dutton Books, 1982.

- Knitter, Paul. Without Buddha I Could Not Be a Christian. London: Oneworld Publications, 2013.

- Kogan, M. S. Opening the Covenant: A Jewish Theology of Christianity. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- MisirHiralall, S. D. (2017). Confronting Orientalism: A Self-study of Educating through Hindu dance. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Other courses may adopt a book circles project. The instructor should select a few different texts for students to choose from. Ask students to develop a self-paced schedule for the semester. Remind students to work on their readings. Have students share at the end of the semester in a book circles discussion forum. Instructors may also invite each student to submit a critical book review of the text.

Dr. Sabrina D. MisirHiralall

Honoring Linguistic Diversity in Online Teaching

One of the most ignored aspects of our students’ identities is their linguistic diversity––what languages they speak. Pedagogical research shows that multilingual students learn more efficiently and deeply when they use their full linguistic repertoire. Even though I don’t speak most of my students’ languages—last quarter, my undergraduates at the large Catholic university where I teach collectively spoke 19 different languages—there are still ways I can help them employ their languages in their learning and prepare to use them in their careers.

This dovetails with other efforts to craft a diverse syllabus. Most of the religions we teach are global religions, so it is appropriate that our courses use texts from all over the world. As a result, some of the readings I assign are translations into English, making it easy to provide students the original. Others have been translated from English into other languages. In addition to asking my library to purchase non-English editions of textbooks, I routinely post translations electronically on our learning management system when I assign individual chapters since many texts are quite difficult for students to obtain, even through interlibrary loan.

In face-to-face classes, many of my multilingual students choose to read materials in English despite access to other translations in order to more easily participate in class discussions, though they often comment on how meaningful they find the attention to their linguistic diversity. I don’t yet have a large enough sample size to say for certain, but I suspect that the more individualized nature of online classes prompts more students to read the texts in their native languages. I especially encourage them to read the non-English version of a text when it is the original language. For my students who are native speakers of that language, this allows them to share their additional expertise with the rest of the class. As with many forms of inclusive pedagogy, the entire class benefits. I have also found that a surprising number of my native English speakers read texts in non-English languages to practice their language skills.

The flexibility of online teaching offers expanded opportunities to engage students’ linguistic diversity. In addition to providing readings in multiple languages, some of my online courses have modules that can be completed entirely in English or Spanish, though often Spanish speakers naturally drift toward a combination of both, which fits with what we know about how people use languages (many linguists now insist that pedagogical efforts to keep languages separate, once common, ignore how the brain processes language and are detrimental both for learning content and for efforts to learn a new language). In these modules, I encourage students to use any combination of Spanish and English for their assignments and offer Spanglish editions of discussion forums as an option.

These kinds of small interventions do not quite approach “translanguaging,” the term linguists use to describe the strategic use of multiple languages in teaching and learning, but they do move my classes a few steps closer to a pedagogy where my students can bring their full selves to the course and utilize all of their linguistic resources for learning.

For further reading:

- Fu, Danling, Xenia Hadjioannou, and Xiaodi Zhou. Translanguaging for Emergent Bilinguals: Inclusive Teaching in the Linguistically Diverse Classroom. New York: Teachers College Press, 2019.

- Hafernik, Johnnie Johnson, and Fredel M. Wiant. Integrating Multilingual Students into College Classrooms: Practical Advice for Faculty. Bristol: Channel View, 2012.

- Mazak, Catherine M., and Kevin S. Carroll, eds. Translanguaging in Higher Education: Beyond Monolingual Ideologies. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Multilingual Matters, 2016.

- Palfreyman, David M., and Christa van der Walt, eds. Academic Biliteracies: Multilingual Repertoires in Higher Education. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Multilingual Matters, 2017.

Dr. Jeffrey D. Meyers

Adjunct Faculty, DePaul University, Chicago, IL

Reflective Journaling in Any Context

In Spring 2020, I taught the ubiquitous, introductory-level world religions course at my teaching-centered small liberal arts college. With no religious studies major, the course attracts undergraduates as a general education credit. I will discuss journaling, something my students do every semester, but which took on new meaning following our switch to remote teaching. As a reflective practice, journals deepen students’ understanding of the connections between religion and the contemporary world and gives them a consistent graded item throughout the semester.

In the classroom, students spend the last five minutes of class writing in physical journals, where they reflect on the lecture, the readings, course videos, or anything that stood out to or puzzled them. Alternatively, they can respond to a discussion question I pose that often builds on their prior knowledge, such as “What do you think is the most misunderstood thing about Buddhism among Americans?” Each day, I read and respond with a check mark or a few sentences which creates dialogues with students, often spurring them to ask follow-up questions and probe more deeply into the material. When we shifted online, this practice moved relatively seamlessly to GoogleDocs. I created individual Docs and shared them with each student and checked them three times a week. In fact, journaling works particularly well online because it simultaneously checks on students’ progress while reassuring them that I care about their progress. Because I decided to make my classes completely asynchronous, the journals replaced in-class questions and became a space for students to have planned personal interactions with a professor.

Journaling sees students as partners in their learning and teaches students the why of what we’re doing. Most students say they take the course to expand their understanding of the world, and journals provide a relatively structured but open way to help them think intentionally about achieving that goal. In addition, the practice asks them to utilize and apply their own knowledge, which validates their learning and experience and is essential in building confidence for many first-generation college students, a large minority of our student population. It is also a way of crafting “religion” as a category of analysis and framing device for the course. Students begin the semester by recording their own definition of “religion” in their journals and then analyze that definition at the end of the semester in a reflective paper, citing four other journal entries to support their analysis. Thus, this activity helps them think purposefully not only about religious practices and beliefs but the nature of religion itself.

Although ideally suited for smaller classes, journaling through GoogleDocs is suitable for online, in-person, and hybrid courses and is ideal in our current uncertain state. The issue of scale is difficult because preferably instructors respond to every student every day; the less they’re checked, the less students will do thorough work. In larger classes, I have divided students into groups which works relatively well, especially if students feel accountable to each other. Alternatively, instructors could respond fully only once a week.

This practice is particularly salient during times of high anxiety because it provides a steady, reassuring outlet for students to explore new ideas.

Gwendolyn Gillson

“Ask me a question”

The abrupt shift to online instruction in March afforded students a better environment to express their curiosity about religious studies. I used their curiosity to foster stronger relationships with students which increased motivation, evident in the quality of their work. I also gained a better understanding of what topics interested students, knowledge I will incorporate into future teaching. This outcome is due to one simple strategy employed for distance learning: requiring students to ask me a question.

Last spring, I taught “Religions of the World” to mostly first-year students at a four-year private university. When the pandemic began and we moved to remote instruction, my class was slated to cover Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. I conducted my classes asynchronously with students submitting written modules on Canvas every four to five days. My modules consisted of primary and secondary readings and videos. Students were instructed to a) compile and define a list important terms, b) discuss one of the terms in depth and c) submit a question about the material. I did not provide guidance for the questions. I was surprised by the topics that students were interested in and what course material they found challenging and thought provoking.

Two of these assignments used the message board. Students were required to post their own reflections on any aspect of the week’s material and respond to another student’s reflection. Although students engaged with each other on the message board, I found that students were more forthcoming with questions when they were addressed to me privately, as opposed to posing a question publicly on the message board or during in-person lectures. I developed stronger connections with students, especially those who rarely asked questions in class or came to office hours.

To take attendance before the pandemic, I had students to write several sentences at the end of class. Students would either answer question I posed or pose questions of their own about the class lecture or activity, the assigned reading for that day, or the forthcoming class. During distance learning, I found that student questions demonstrated more nuance and curiosity when they were part of a written module than those written at the end of class. This may be explained by the fact that asking a question was central to an assignment and students had more time to construct a nuanced question compared to the few minutes at the end of class.

I was surprised some of my students’ questions. Several expressed surprise at the diversity of contemporary Islam. I did not anticipate this reaction, and it suggested to me that many students view Islam as inherently monolithic while they readily recognize diversity in Christianity. I was able to address this perception with the class. Some students drew upon their cultural knowledge to ask about topics not covered in class, such as why some Jewish people wear yarmulkes or the meaning of the “Holy Ghost” in the Christian tradition.

Requiring students to ask a question accomplishes encourages metacognitive reflection on their learning process. Students who ask questions that speak to their own curiosity or life experience expand their knowledge and understanding of the course material. I often responded not merely by answering their question but to refine or nuance their questions, to help them refine their critical thinking skills.

Brian Hillman

Indiana University, Bloomington

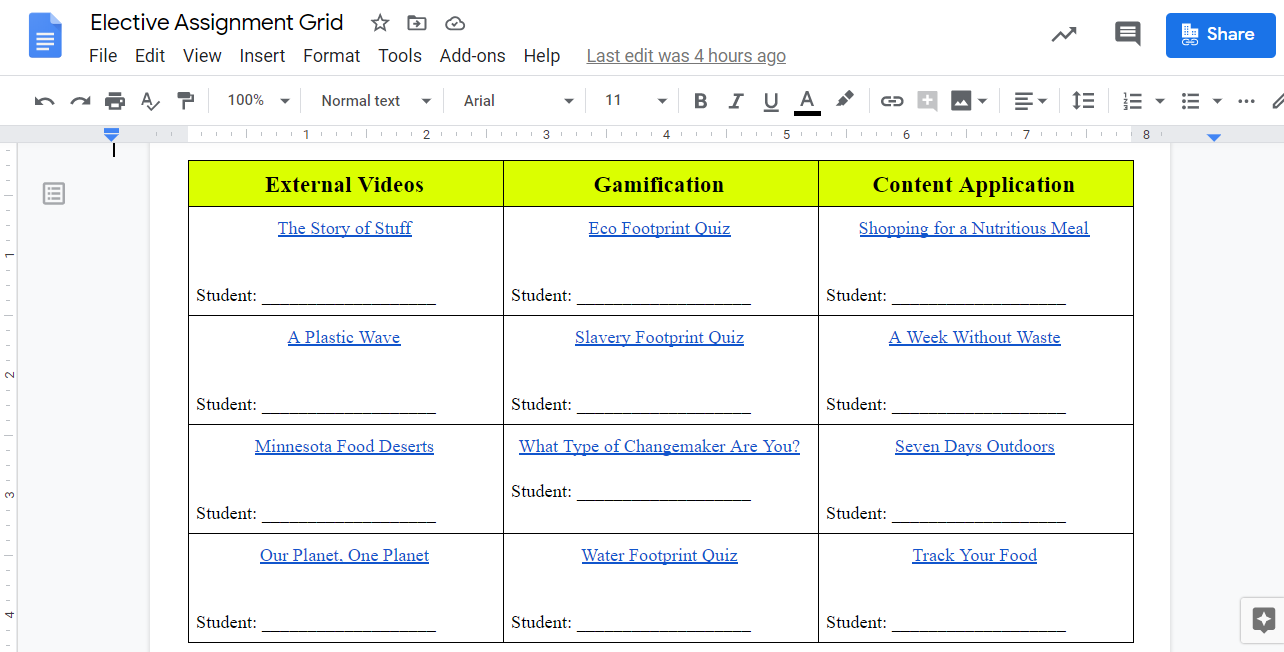

Reaping the Benefits of an Elective Assignment Grid

An elective assignment grid is a highly effective teaching tool that faculty may utilize in hybrid and/or online courses. One realistic context to envision its potential is a 200-level theology course offered in a Catholic, liberal arts university to undergraduate students aiming to earn credit for their major or general education program. While this teaching practice may prove useful at various points in an academic term, its intended pedagogical purposes in this consideration are twofold. The first is to foster open and critical thought about ecology in the context of Catholic Social Teaching. The second is to offer multimodal learning opportunities for interactive, personal engagement with some integral themes and instructions presented in Pope Francis’s 2015 encyclical, Laudato Si.

Using this teaching practice allows students to select learning activities from a grid posted by their instructor in one’s learning management system. In the aforementioned 200-level theology course, an elective assignment grid could consist of three categories: external videos, gamification, and content application. The following instructions demonstrate how to introduce this teaching practice inside a learning management system:

- In preparation for next week’s discussion, each member of your small group is responsible for completing one of 16 learning activities. The 16 options appear in this Google document: Elective Assignment Grid

- Once you decide which of the 16 activities you want to complete, place your name under the listed activity. No more than one person may choose or complete the same activity. Names entered inside the grid will automatically appear for others to see.

Appearing inside a Google document, the Elective Assignment Grid would look like this:

The functionality and inherent value of such a design depend upon the quality of the presented activity options. In the category of external videos, for instance, The Story of Stuff (Free Range Studios, 2007) provides a compelling snapshot of the throwaway culture Pope Francis aims to end in Laudato Si (2015, section 22). In the category of gamification, completing a slavery footprint quiz fosters personal awareness and contemplation of how true ecology is always a social commitment to integral, human ecology and the common good (Francis, 2015, section 156). In the category of content application, comparing the costs and abilities to procure ingredients for a nutritious meal in and outside of a food desert offers first-hand insight into the challenges of ecology of daily life (Francis, 2015, section 147). The varied nature of options such as these three brief examples promote affective learning, expand understanding, and heighten awareness of the Pope’s encyclical teachings. Moreover, such an instructional design complements desired learning outcomes and promotes peer-to-peer learning when done in preparation for subsequent class discussions.

Although students complete unique activities and engage with different content, the elective assignment grid can set the stage for a robust discussion. In the week that follows this assignment, for example, distance learners could use Flipgrid to share details of their respective learning activities and explain how those activities connect to Laudato Si. In reply, members of their discussion group could also utilize Flipgrid to offer feedback and make connections to their own activities and insights. Sharing their experiences and gathering feedback—even in a digital platform—fosters both individual and peer-to-peer learning. If teaching in a hybrid setting, using the discussion technique of inside/outside circles is a worthwhile, in-person alternative. The active sharing and discussion that result from this practice afford greater understanding and engagement.

Moreover, the multimodal content delivery of an elective assignment grid affirms different learning styles, facilitates self-paced learning, and provides the variety that many students seek and appreciate—particularly in an asynchronous, self-paced learning environment. The success of this teaching practice hinges on an instructor’s creative compilation of assignment options and students’ receptivity and cooperation. In my experience, students typically embrace the ability to choose their modes of learning. An elective assignment grid is adaptable in humanities and STEM courses alike. It invokes a sense of challenge while honoring personal interests and abilities. Class sizes are not a prohibitive barrier to the success of this independent learning approach.

For additional insight and discussion of this type of teaching practice, see Angela Danley and Carla Williams, “Choice in Learning: Differentiating Instruction in the College Classroom,” InSight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching 15 (January 2020): 83–104, and George M. Jacobs and Francisca Maria Ivone, “Infusing Cooperative Learning in Distance Education,” TESL-EJ 24, no. 1 (May 2020): 1–15.

Joyce A. Bautch, PhD

Associate Professor of Theology

Saint Mary's University of Minnesota, Winona, MN

Contemplative Exercises and Pedagogy Online

I teach “Buddhist Meditation and Practice” and “Religions of Asia” courses in a Jesuit university. As a certified Cognitively-Based Compassion Training® (CBCT®) contemplation instructor and an advocate for contemplative pedagogy (CP), I found that CP resonates with the Jesuit signature pedagogy, the Ignatian Pedagogical Paradigm (IPP), which includes five elements: context, experience, reflection, action, and evaluation. CP’s emphasis on students’ investigating their own contemplative experience parallels the IPP’s priority for experience, which encourages teachers to create a multidimensional learning environment. Inspired by those two pedagogies, I have strategically integrated CP with the IPP to promote students’ experiential learning. Courses have been online since the spring of 2020, so I have been utilizing Zoom’s features to lead contemplation activities synchronously in my courses. For example, I have modified exercises for an online platform: tea ceremony (taste), cup contemplation (visualization), contemplative movement (kinesthesia), ritual music (hearing), in-class journal entry (reflecting), and CBCT Modules I and II practice (focus and awareness). To help students understand the pedagogical purpose and to avoid implied proselytizing, I contextualize each activity in the relevant scholarship and texts. I also inform students of the resources of the activity design. The example below details my adaptation of a contemplative movement assignment in a session on Chan Buddhism on Zoom. The same principles can be applied to other contemplative exercises.

First, students study the legendary poem contest between the two Chan masters to determine the sixth patriarch of the Southern Chan school, as mentioned in the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch (Liuzu Tanjing). Afterwards, they discuss which poem resonates most with their own preference. I then share my field observation of a “Chan dance” (chan wu) workshop in Yutian, China, in the summer of 2018. As a rising cultural movement, the Chan dance is different from monastic walking meditation, andis led by laypeople with music and dance costumes. It is a spectrum ranging from art performance to Buddhist practice. To give a kinesthetic dimension to students’ learning related to this cultural phenomenon, I conduct a contemplative movement exercise in the next meeting. To prepare students to participate, I ask them in advance to wear comfortable clothes, use a computer in a place where they can turn on the audio, and have three feet around them so they can move freely. Students can also sit for this exercise if standing is not convenient in their locations. I choreographed movement to go along with the poem I composed based on my inspiration from the verses discussed in class. Before we start, I do a screenshare to show students my poem next to the original verses for their comparison. I describe how my poem and the choreography go together. Students follow my lead through a five-minute dance accompanied by sedate music. While we did this virtually, we can still see each other and perform as a community. I felt a sense of connection, even though we were physically distant. To apply CP’s third-person, critical-thinking approach and the IPP’s element of reflection, each contemplation activity is paired with an assignment in which students compare and contrast their contemplative experience with the relevant concepts mentioned in the readings. For this movement activity, they do an in-class journal entry to reflect on what they have noticed about themselves. In addition to bringing awareness of their feelings, this performance experience gives students a glance of contemporary uses of dance and poetry to approach Chan without embracing the Buddhist worldview.

While I conduct contemplative exercises on Zoom as I would have in person, not every activity can achieve the same pedagogical goal in an online format. For instance, I noticed that the feeling of appreciation was missing from our virtual tea ceremony, in which students prepare their own tea and cookies instead of receiving the service from me and other classmates. Zoom’s breakout room feature is good for group discussion, but is not workable for pair exercises that require the teacher to lead. However, through appropriate adaptation and communication with students, Zoom still offers a platform that allows instructors to design a multisensory experiential learning environment.

Gloria (I-Ling) Chien, PhD

Assistant Professor of Religious Studies

Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA