Dismantling the Seat of Power to Enable Reflexive Inquiry

Empathy, as I understand it, is the internalization by the less powerful of the feelings and perspectives of people who hold power. In all institutions, then, empathy exists in relation to power structures that define the organization and its bureaucratic relationships. Universities and classrooms are institutions with power structures.

In higher education, the power structures of courses, disciplines, and majors become sites where this definition of empathy can be explored and interrogated. At the institutional level, students may take classes in disciplines that do not interest them but serve the institutional curriculum. They may read books and articles by people who have been granted the position of authority by virtue of their work being memorialized in writing and brought into the classroom. And students must work with their professors who will pass judgement on them at the end of the term through grading. The act of grading implies that in order for a student to be successful, they must continually expose their inner thinking to a person who will determine their “worth.” Put another way, the professor occupies an institutional seat of power that demands student empathy, that is, for the student to align their inner processes and feelings with what they think the professor wants them to present for success.

By the time a student is in a higher education classroom, they will likely know what the relationship between student and instructor should be. They will have had more than a decade of formal education experiences where they have learned to push down their own emotions to ensure that the professor remains “objective” with them. The power structures at play will encourage an environment in which they never openly question the professor’s perspective nor the course materials. They may not even think the professor has a perspective that is worth interrogating, as the professor is the authority in the classroom. The student internalizes the empathetic feelings they should have towards the person, the curriculum, and the institution they are trying to please. This has significant consequences for all courses, but it is particularly disquieting in religious studies courses which interrogate ethical, moral, and philosophical thought. To maintain our moral bearings to the profession and to our students, then, it is imperative to break down the classroom’s seat of power to enable true exploration of the self for the student. By doing so, the student can engage in reflexive inquiry that allows them to understand the roots of their perspective, and place that perspective in conversation with others, such as their fellow students and texts they are engaging, to create new knowledge and lines of inquiry.

There are two concepts that should be better understood in order to dismantle what I refer to as the “seat of power”: first, what I mean by the seat of power itself and, second, the implications of this concept to my definition of empathy.

The Seat of Power and Empathy

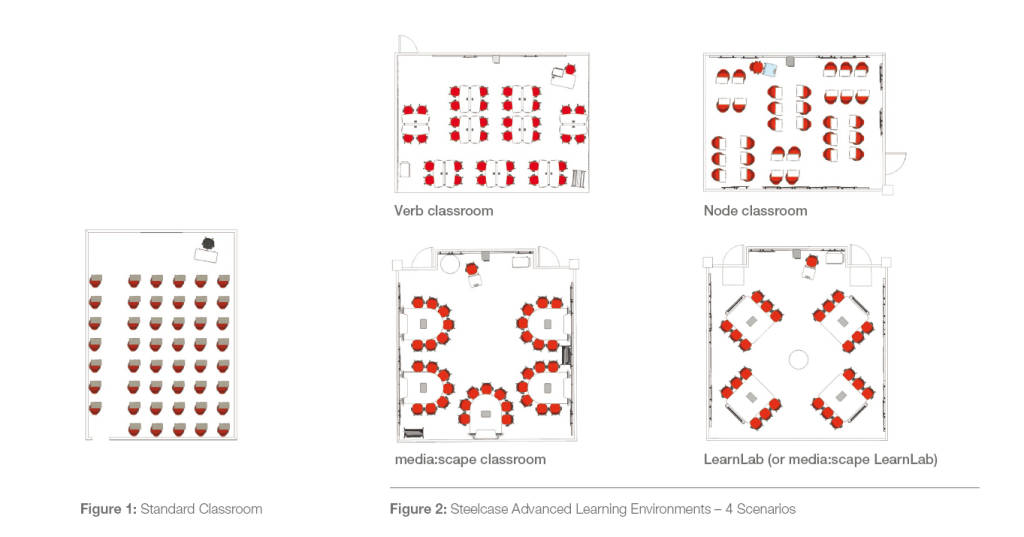

Steelcase, a furniture vendor that works with many institutions of higher education, produced a white paper on increasing engagement through classroom layout, advocating for flexible furniture which will allow a classroom to shift in design. They provide a map of five different classroom configurations, one being a standard classroom, the others being “Advanced Learning Environments.”1 Despite the flexibility of the advanced learning environments, there is still a seat outside of the group that is designated for the professor. I call this “the seat of power.” Its existence makes physical the ideological baggage of the classroom by placing the professor as the focal point. Regardless of how a classroom is set up, the focal point is, most of the time, the professor who is functionally interchangeable. That is, the professor can have a substitute who will occupy the seat and hold the same role regardless of being a different person. Likewise, the professor always assumes that the student will look towards them and defer to their interpretation rather than the student’s own.

From the viewpoint of the zero point of orientation gained in empathy, I must no longer consider my own zero point as the zero point, but as a spatial point among many.

– Edith Stein2

In his essay “Writers, Intellectuals, Teachers,” Roland Barthes argues that occupying that seat, rather than a position of power, actually creates a position of vulnerability. Though it seems on the surface the professor analyzes their students, in reality it is the other way around. The students listen astutely to the professor, take notes the professor does not see, and then give back what they think will be most well received ideas to the person they have analyzed. “In the exposé, more aptly named than we tend to think, it is not knowledge which is exposed, it is the subject (who exposes himself to all sorts of painful adventures). The mirror is empty, reflecting back to me no more than the falling away of my language as it gradually unrolls.”3 The knowledge and deference students reflect back to the professor in the seat of power often does not accurately depict them as a person. Rather, students reflect their internalized role in the learning space.

To better reflect actual student lives and voices, it is important to play with the space of learning and seat of power. Even in the standard classroom design, it is imperative that the configuration of students and seat of power be challenged or allowed to shift so that the students—especially those engaged in classrooms that are designed around ethical, moral, and philosophical thought—understand that it is possible for power to have multiple perspectives, and that their own perspectives are just as powerful. Below, I will make some practical suggestions for how to accomplish this. Before we do, however, empathy must be understood in terms of the seat of power.

But what is empathy? There are many definitions and very little consensus.4 For the past twenty years or so, there has been exploration into the neurological basis for empathy, which has led to dead ends and almost-connections. While there is evidence of physical mirroring (when someone unconsciously copies the movement of another), there has not been a study that conclusively proves that people are able to feel the emotions of another. Instead, bias, familiarity, and experience work together to create an emotion that is similar but not the same; the emotion remains grounded in the experience of the empathizer.

Further, given that biases, familiarity, and experience are not universal, the more distance a person has from another creates a deficit in the ability to make a model of another person’s emotions.5 Rather than doing a review of all versions of empathy, I will explore a brief definition from Theodor Lipps, one that is also used in the work of Derek Matravers. Lipps states that empathy is the “satisfaction in an object, which yet, just so far as it is an object of satisfaction, is not an object but myself; or it is satisfaction in a self which yet, just so far as it is aesthetically enjoyed, is not myself but something objective.”6 For students, professors are often an object of the classroom that contains the knowledge and power to determine if a student can pass or fail. The position of a professor is the baseline for objectiveness, and they are the object that provides the cues for what a student should mirror in terms of work and actions. The professor serves as Stein’s zero point.

In Practice

To be a student is to be in a vulnerable position. A student enters a space tacitly saying, “There is something I do not know and, given that you are leading the course, we are entering an agreement where you get to re-program me, and I won’t know any better.” The best method I have integrated into formal classroom learning spaces to break the spell of students over-identifying with me is to find meaningful ways to hand the seat of power to students and have them work with their fellow classmates to understand the material and its relevance. Doing this in an intentional way allows the students to show up as themselves, be vulnerable, and learn from each other just as much, if not more, than they learn from me.

In the first week of any course, students decide if it is safe to be vulnerable with a professor and their fellow classmates. To help students make that decision, I offer a class period near the beginning of the semester dedicated to learning about me, the course, and our roles in this space. I let them ask questions about me that they think might influence how I approach the material or subject of the course (within reason). Often these questions are about my age, where I grew up, if I have kids, why I was teaching the course, etc. I also create a very short introduction lesson that highlights the arc of the course, discussing my hope that they should be able to make connections across material in their own language by the end of the term. The purpose of this is so that we are reminded that everyone in the room is a whole person, including myself. My goal is not to hold my knowledge over them, but rather to help guide them through material. This allows them to have an expanded sense of the different things I am balancing, just as they are balancing other courses and parts of their life.

The last part of this day, however, is always explaining the seat of power. I have the students tell me about the very first day of class. I ask them if there is anything noteworthy they remember about how I started the course. They always remember me being late and us not doing much. They never remember that I did not introduce myself. Inevitably, even in the questions they asked, they do not ask me my name. This is the point where I would introduce myself with my name and role in the course. I point out that the spot in the front of the room that everyone looks towards is the seat of power, which is why they never questioned me once when I went to that seat and began speaking as though I had authority over the course. I let them know that they will all occupy the seat of power at some point during the semester. While it may seem daunting, the funny thing about cultural power structures, such as the classroom, are that people have been inevitably trained by cultural reproduction to believe the person at the front of the room; that person is rarely questioned. But if a course is an ethical and moral thought course, it is imperative that they do just that.

Regardless of the level of a course, it is important to allow students to shape part of it by occupying the seat of power. For a 100-level course, it is safe to assume that many of them do not have the fluency in the subject matter to be enlisted as co-teachers. However, students do have many years of experiencing the world and other classrooms, and thus, they come into a classroom with many ideas about how learning works. There are two things I do to dismantle the power structures and give students the opportunity to think through their own perspectives, even in a 100-level classroom. The first is having a “show and tell” at the end of every class session. Show and tell consists of a student sharing something they are interested in, they read, or they engaged with that is in some way related to the course material. My goal is getting students to articulate why they have brought it to the course and how it is related. Through this exercise, I learn what is of interest to the students so I am better able to connect course material and give them some control over course content, essentially granting them some access to the seat of power.

The other exercise I do to reorient the seat of power is changing my model for pop quizzes. Rather than giving quizzes where the individual student repeats rote facts they’ve encountered in the readings, I create group “pop quizzes.” These take up either half or all of a session and occur at points in the semester where I feel students are struggling. In these quizzes, students work in groups to create a short presentation on an assigned theme in a format that is related to the course material (e.g., if we are learning about advertising, they create an ad; if we are learning about digital cultural reproduction, they create memes). While they work in their groups, I am available for questions if they are stuck or unsure about their understanding which allows them to engage with me outside of the seat of power and instead as a consultant to their own knowledge production. After the group work is finished, students present their work to the class. In this way, the students create their own study guides, learn the structure of the material, and have a chance to speak with their classmates around common points of understanding or misunderstanding, and they occupy the seat of power with other classmates. Students know that traditional pop quizzes are given without any notice for the purpose of demonstrating knowledge and retention of course concepts. The group pop quizzes are designed to do the same. The anxiety of the announcement enables a moment of reflexivity that, due to the cultural norm of quizzes, allows them to be more productive in their groups. Additionally, once they realize that they don’t have to do it alone, they have a shared experience of relief, creating psychological space to speak to each other about before they dive into the work.

These practices happen in 100- and 400-level courses. The 100-level courses are foundational for media studies. They require that I lead the discussion to ensure that once students move on, they have the knowledge they need to be successful. The 400-level courses are co-led by myself and the students. At this level, students should be able to apply and create new knowledge grounded in media and culture. These courses are designated as philosophical and ethical thought. As the course level increases, I work towards having students lead the first session of major units within the course. Working in pairs, they are given half of a class session to present an introduction to the new topic and lead the initial discussion. On the days where students present, regardless of how the class is set-up, I sit in a location where I am not in their direct line of sight. This means if they look towards me for confirmation that they are doing a good job or request reassurance, it is very obvious to the class. I do this because students need to speak to and with each other. In this way, the experience of discussion leadership comes from both the professor as well as x number of students depending on the size of the course. This creates a community of practice where students become accountable not just to the professor but to each other. It enables each student to experience leading a portion of the course, ensuring their viewpoint is represented and reflexively interrogated so they are able to articulate the connections they are making to the course material. This activity, combined with being open at the beginning of the course about who I am, forces the students to listen to and expect perspectives other than my own. It takes time to cultivate this classroom into a dialogic space, but it shows potential in creating a dynamic in which each is mutually respectful of everyone's unique positionality without feeling the need to see the world or feel the world exactly as others do. In my experience, this practice is significantly more empowering than the “empathy” we normally expect of students toward power-players in traditional classes.

The balancing of this activity can be tricky, and sometimes students do not deliver what needs to be delivered or are disrespectful towards others in the space. In cases of misinformation, I step in and take over, reminding them that regardless of how much I hand the seat of power over to them, it is still my assigned seat. The resulting discussion allows students a chance to interrogate the concept in a meaningful way with authoritative information. I also revisit the misunderstood idea a few days later, speaking to the group that presented first to make sure I have a clear understanding of their perspective and justification for what they presented as well as to make sure they were okay with how the discussion went and are still comfortable in the course. In instances of disrespect, I take a more assertive role and tell the student who was being questioned in an inappropriate way to not respond, and then announce that I would be taking advantage of my permanent role in the seat of power. In this case, rather than focusing on the one-on-one interactions with the students, I have students raise their hands to find the point where the interrogation needs to start. I invite an initial response at the time where I bring to the surface the cultural learning that led to their belief and provided counter-evidence so they understood how and why their perspective, while a valid perspective, is biased. I then spend the next two class periods in that unit delving into the topic starting from the point of discontent we identified.

The benefit of this assignment is students stop trying to please the seat of power and instead think through what the course can be for them. They do not focus on saying what is right or what will make me happy as the professor, in the way we think of power-based classroom empathy. They become open to asking about misunderstandings and bring up things that they think are related but are unable to articulate fully. More than that, as students stop trying to adjust to me and my feelings, or how they think I see them, they become open to playing with their own perspective and beliefs. I, in turn, am able to provide feedback, present constraints, and give clarity at points where students may be stuck. This role, outside but connected to the seat of power, deepens their own learning and helps them produce better work. They understand that who they are, independent of how I may feel about them or their own moral and ethical stances, will have no bearing on their grade. I make sure to reiterate this any time we encounter a touchy topic, at times stopping the course if there is likely a counter-perspective that can enter into conversation. The goal of the course is not for them to adopt my stance towards things (in the way we traditionally think of empathy in the classroom), but instead to be able to articulate their perspective through a critical engagement with materials from the course and their everyday lives. The course design ensures they are successful and that their voices are not lost. Given that there is only one of me and many students, if they have to fall into empathy, I would rather it be with each other in a space of communal knowledge-making.

Towards Learning

The goal of teaching for me has never been about giving “correct” knowledge to my students. It is instead about co-learning through exploration. By letting go of empathy (defined as understanding the feelings and beliefs of those in the seat of power), I am able to remove some of the barriers that exist around the seat of power in the classroom. I am still the authority in the classroom space. However, by acknowledging that reality regularly, and pointing it out when I have to enact that role, students are aware of what's happening in a way they normally are not. The more radical turn, then, is to see students as people who likely have a perspective that the professor might not just learn about, but also, will watch evolve into something delightful, especially when they are given the seat of power in their learning. Additionally, professors reflexively looking at ways they enact power in their courses can play with ways of dismantling the tendency of students to anticipate what they think a professor wants to hear. By creating a space that is centered on the shared humanity of everyone in the room instead of the power of a professor over their students, students are able to ask for what they need to succeed without fear of upsetting or disappointing ”the person in power.”

1 Steelcase, How Classroom Design Affects Engagement, June 2014, https://www.steelcase.com/research/articles/topics/active-learning/how-classroom-design-affects-student-engagement/.

2 Edith Stein, On the Problem of Empathy, trans. Waltraut Stein (Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 1989), 63.

3 Roland Barthes, “Writers, Intellectuals, Teachers,” in Image, Music, Text, trans. Stephen Heath (London: Fontana Press, 1977), 194.

4 Derek Matravers, Empathy (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2017).

5 See Jean Decety and William Ickes, eds., The Social Neuroscience of Empathy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009) and Susan Lanzoni, Empathy: A History. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018).

6 Theodor Lipps, “Empathy, Inward Imitation, and Sense Feelings,” (1903) in Philosophies of Beauty: From Socrates to Robert Bridges being the Sources of Aesthetic Theory, ed E.F. Carritt (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1931), 253.

Jade E. Davis is the director of digital project management at Columbia University Libraries. She holds a PhD from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in communication studies with a focus on digital media, emerging technologies, culture, and performance studies. Her research interests center on decolonization, technological equity, emerging technologies, ethics, morality, and history. Her most recent research has focused on decolonization, empathy, and emerging technology.

Jade E. Davis is the director of digital project management at Columbia University Libraries. She holds a PhD from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in communication studies with a focus on digital media, emerging technologies, culture, and performance studies. Her research interests center on decolonization, technological equity, emerging technologies, ethics, morality, and history. Her most recent research has focused on decolonization, empathy, and emerging technology.