Why the “Science for Seminaries” Initiative?

The conversation between the Association of Theological Schools (ATS) and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) about collaborating on a project like Science for Seminaries has been going on for over a decade. The program took shape three years ago with funding from the John Templeton Foundation. My observations in this essay focus on the overall importance of the project, as well as some of the key findings from its research component.

The Importance of the Science for Seminaries Initiative for ATS

“We live in a time when natural science, social science, engineering, and technology are among the primal shapers of our civilization.”

– interviewee from a mid-sized Evangelical Protestant seminary

Science often touches on the “big” questions of life—questions that require responses from both science and theology. The ATS sees engagement with science as a way to engage the important questions of our current culture.

The mission of ATS is “to promote the improvement and enhancement of theological schools to the benefit of communities of faith and the broader public.” As an organization that accredits schools that are forming religious leaders, ATS helps schools reach their aspirational goals. We want pastors to be informed as they teach, preach, care, and counsel in ways that are both theologically faithful and scientifically informed.

In their current form, the ATS Standards of Accreditation focus on helping students understand “cultural realities and social settings,” including the insights of cognate disciplines such as the natural sciences. An excerpt from the Master of Divinity Degree Standard (A.2.3.1) exemplifies this focus:

The program shall provide for instruction in contemporary cultural and social issues and their significance for diverse linguistic and cultural contexts of ministry. Such instruction should draw on the insights of the arts and humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences [my emphasis].

The Standards of Accreditation both hold institutions accountable and support the institutions and the people that serve in them as they educate seminarians in a broad range of areas of capacity. To the degree that the standards explicitly and implicitly recognize the formative role played by the natural sciences in shaping and informing any number of cultural contexts, ATS readily endorsed the work of the Science for Seminaries initiative as a valuable resource for its member schools.

Seminary graduates are leaders in their communities, and parishioners look to them for guidance not only in spiritual matters, but also on a whole range of issues that aren’t explicitly “spiritual” or “theological” but are culturally anchored—issues that confront them in society and have deep theological implications. We don’t imagine that seminarians will or should become scientists, but they must be prepared to address such issues, even in a basic—albeit well-informed and well-nuanced—way. Unless seminarians are exposed to these issues and given an opportunity to explore the spiritual and theological implications of these issues for themselves, they may be ill-equipped to accompany their congregants with the excellence and authenticity expected of ministry leaders.

Student Interest and Preparation: What the Data Reveal

In 2017, as part of the larger Science for Seminaries initiative, ATS conducted a baseline study of seminary engagement with science, involving faculty and administrators at ATS schools. We collected perspectives using a fifty-item survey of faculty at ATS Protestant schools, interviews of key informants at thirty Protestant schools, and content analysis of documents collected from the same thirty schools. Complete reports can be found on the ATS website.

What follows are a few of the findings that I think highlight the importance of the initiative for ATS.

In the survey, we asked faculty how prepared they felt their students were to deal with scientific issues. Only 21% agreed their students were “well prepared” to address questions of science in the latter’s future ministries. Very few faculty were overwhelmingly positive about their students’ ability to respond adequately to questions related to science or effectively address in a pastoral setting congregants’ science-related concerns. We found this perspective to be consistent across the variety of Protestant schools. In addition, faculty were asked to approximate the proportion of students who come to seminary with a science degree. Faculty estimated about 15% come with a natural science degree, 28% with a social science degree, and 59% without any science degree.

These faculty perceptions about student preparedness confirm student self-perceptions. In its Graduating Student Questionnaire, ATS annually asks graduating students how effective their education was in facilitating growth in twenty different skill areas, including the ability to integrate science and theology. Over the last five years, this item has consistently ranked second from the bottom, with an average of 3.6 on a five-point scale. So faculty concern for students’ lack of preparation to deal with science in their ministries appears to have some foundation.

Faculty perspectives paint a slightly different picture about student interest in scientific topics. In response to a question about student receptivity toward the integration of science and theology, interviewees remarked: “Oh, they love it” (from a mid-sized Mainline Protestant school); or “I think our students have really found it meaningful” (from a large Evangelical Protestant school). Indeed, seven out of ten faculty believe students are interested in the topic, though no more than other areas, and almost two out of ten feel their students are particularly interested in scientific topics. Only about 10% say students are not interested.

It should be noted, however, that evaluations of student interest in, or willingness to engage the intersection between science and theology were not always positive. One interviewee from a large Evangelical Protestant school stated it this way,

If you don’t have a theological system that has a robust creation mythology, you are lost. I’ve seen that lostness occur to some students. It’s a terrible thing to do. The ethics of teaching, where you destroy the naiveté of folks. Man oh man, one has to handle those carefully.

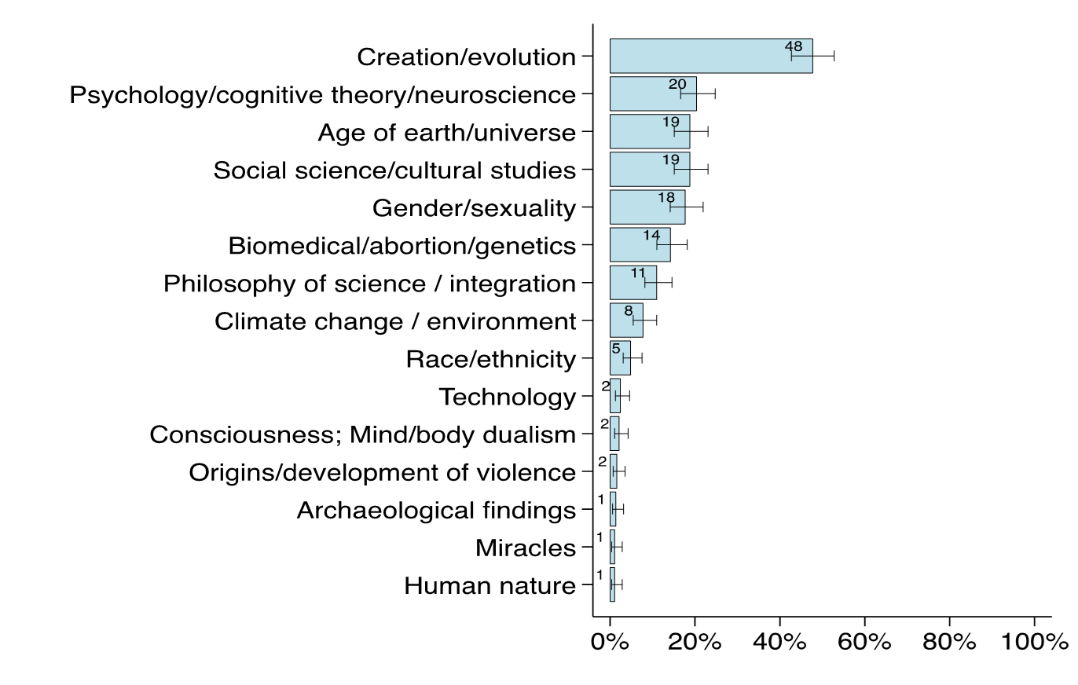

While we found that ecclesial family is not a predictor of a school’s engagement with science (i.e., Evangelical and Mainline schools were equally likely to engage), when faculty did face student resistance, it was typically around certain controversial issues. Over 60% of the faculty surveyed identified a range of scientific issues that typically provoke controversy among students (see Fig 1).

Figure 1 – Scientific Areas Named by Faculty as Causing Controversy among Students

As we see in Figure 1, creation/evolution unsurprisingly dominates the list of issues generating controversy among students, with nearly half of the surveyed faculty including this issue in their list. At the same time, it is not the only area of controversy. The second most common controversial area was coded as psychology/cognitive theory/neuroscience, with 20% of the faculty naming topics in this category. Even the use of social sciences in theology (e.g., how appropriate it is to incorporate such disciplines) is an area seen as causing tension for students.

Interestingly, when faculty were later asked in the survey to name what further steps their school could take to advance the engagement of science, about 20% said their school should “advocate more for [a particular] issue,” and very few of these respondents named anything related to creation/evolution. So, while faculty named this as a controversy, they most likely see this as a student issue or see it as having far less moral or social justice relevance than issues related to climate change, biomedical ethics, and human sexuality, all of which faculty named more frequently.

A Question of Pedagogical Ethics

The “ethics of teaching” mentioned in the quote above invited a pause in the research project. We paused to think carefully about how engagement with science can be disorienting for seminary students. While undeniably important for accompanying their parishioners, equally undeniable is the fact that, for many students (and faculty?) this engagement can and oftentimes does trigger a process of deconstruction of long-held beliefs and values, or at least long-held interpretations of these beliefs and values. If graduate theological education had its own “Hippocratic oath,” in what ways would instructors teach so that they “first, do no harm”? Would “doing no harm” involve moving forward with deconstruction at all costs? Or would it mean subordinating all deconstructive implications to an imperative to leave preexisting belief systems intact? Perhaps the most helpful approaches to the important questions of pedagogical ethics in this regard are more nuanced and less dichotomous than these extremes. We might ask ourselves, for example: in what ways is it irresponsible as an instructor to deconstruct such systems without thought to the reconstruction process? Or: how irresponsible is it to deconstruct without attending to historical or socio-political realities?

An important theme that emerged from the interviews highlights the need for paying close and careful attention to the pedagogical ethics of valuable but potentially sensitive projects like Science for Seminaries. In their report of the interview phase of the research project, Atwaters and Park-Hearn state the following:

A few interviewees share their concern for African American students whose social and historical contexts give ample reason to view science as a threat. This is an all-too-critical issue that must factor into any conversation about the place of science in theological education. This informed and responsible critique of the way that science has been used to oppress and harm must challenge any attempt to make normative a singular construal of science and its place in schools, churches, and in individual and communal lives.1

This conclusion was informed by the reflections of several interviewees responding to the following questions: 1) “What areas of science would be considered off-limits at your school?”; 2) “How have students responded to the integration of science?”; and 3) “How is science relevant/irrelevant to theology in ministry?” To the first question, an interviewee from a large Mainline Protestant school offered, “I think our students are—they’re very leery or anxious about the ways in which science can be used as a source of domination….” Responding to the second question, an interviewee from a large Evangelical Protestant school explained, “I suspect that some of our students, especially who are coming from overseas or from outside of the US and Europe, are a little less comfortable with a full-bodied integration with science.” And to the final question, one interviewee from a different large Evangelical Protestant school responded,

Science is still largely an opportunity for the privileged in our country, so this gets back to the social issue….the black community in general in the United States does not perceive science to be their friend. They see the way that science has been used to actually justify their treatment.

Such observations are particularly important as we consider that, by 2025, it is estimated that students of color will comprise the numeric majority of students in ATS schools. This behooves us to keep in mind an important pedagogical question: how will our teaching—especially the engagement with science—take into account this projection?

Concluding Reflections

According to a report of findings from a 2013 Religious Understandings of Science research project commissioned by AAAS and its Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion (DoSER), Evangelical Protestants are much more likely than the average person to rely on “a religious text, a religious leader, or people at their congregation” for questions about science.2 At least some of these religious leaders are being formed in ATS schools, and it is our hope that graduates of theological schools will be better informed about issues related to science and will therefore provide more effective leadership in communities of faith and other places of service.

Interviewees from the ATS 2017 baseline study of seminary engagement with science further indicated the importance of seminary engagement with science. One excerpt (from an interviewee of a large Evangelical Protestant school) illustrates this aptly,

I think I have to rank [science] fairly high for a couple of reasons, in that it touches every area of our life. Who am I as a human being? What is my destiny? What does it mean for me to live? What does it mean for me to die? All of those questions are, at least in part, both theological and scientific questions.

Theological education and science must see each other as important partners, and ATS has appreciated the collaboration with AAAS and DoSER. ATS schools and AAAS have a common interest in the success of such collaborative efforts, including that they be based on both good science and good theology. There is a great need for theological education to engage these conversations, and it is important to continue to build a sense of trust and mutuality between the fields. We want theologians to have a better understanding of science. We also want scientists to have a better understanding of theology. Through the conversation, the Science for Seminaries project is helping to clarify the kinds of questions each is equipped to answer and those each is not. The two fields need to rely on each other to nurture faith leaders who are ready to address society’s current and future important questions.

1 Sybrina Y. Atwaters and Rebecca Jeney Park-Hearn, “Engaging Science in Seminaries: Report of Interview Findings,” Association of Theological Schools, March 29, 2017, 24–25. http://www.aaas.org/sites/default/files/content_files/RU_AAASPresentationNotes_2014_0219%20%281%29.pdf

2 Elaine H. Ecklund and Christopher Scheitle, “Religious Communities, Science, Scientists, and Perceptions: A Comprehensive Survey” (Paper Presentation, Annual Meetings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Chicago, IL, February 16, 2014), 13–14.

Deborah H.C. Gin, PhD is director of research and faculty development at the Association of Theological Schools. Her areas of research include pedagogy, higher education administration, and diversity and inclusivity. Gin is a regular blogger on leadership issues related to Asian American women, has been a frequent invited speaker on topics related to race, excellence, and inclusion, and is a member of the Association of American Colleges & Universities’s VALUE initiative Intercultural Competence rubric development team.

Deborah H.C. Gin, PhD is director of research and faculty development at the Association of Theological Schools. Her areas of research include pedagogy, higher education administration, and diversity and inclusivity. Gin is a regular blogger on leadership issues related to Asian American women, has been a frequent invited speaker on topics related to race, excellence, and inclusion, and is a member of the Association of American Colleges & Universities’s VALUE initiative Intercultural Competence rubric development team.