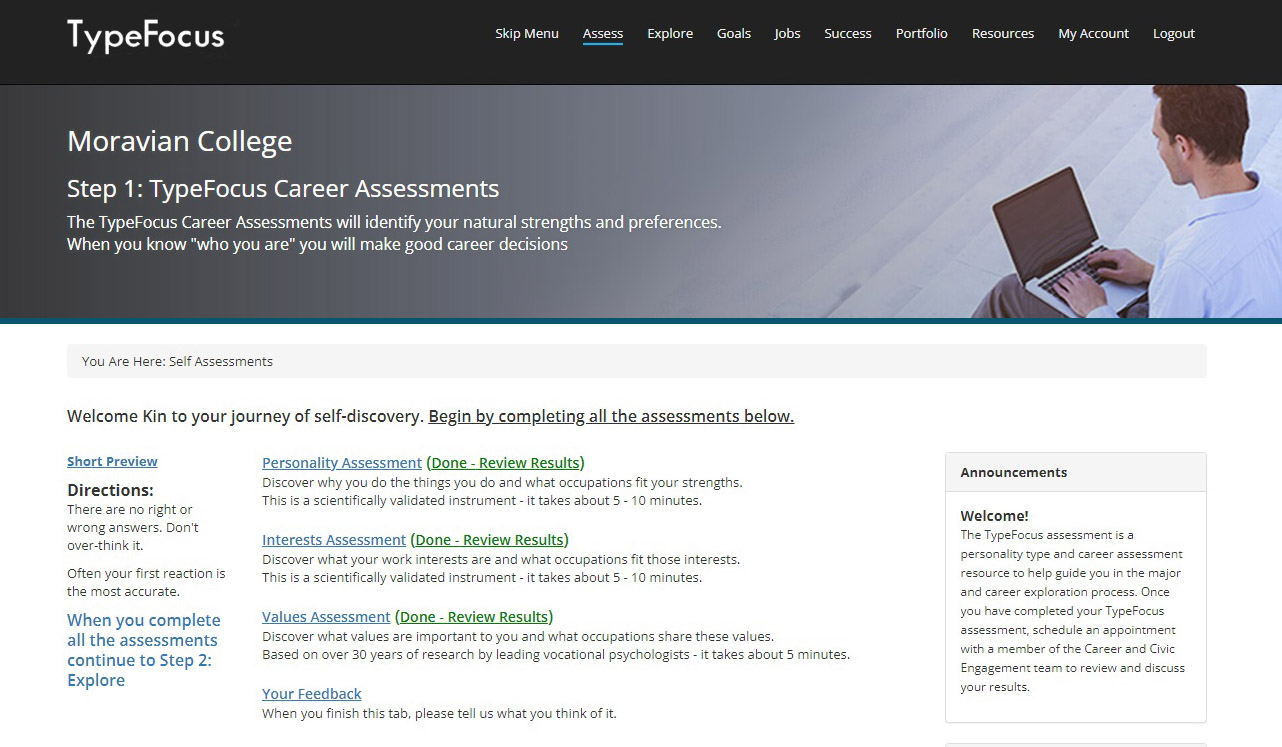

All first year students at Moravian University take an online personality assessment during the summer and then meet with their career development strategist. This software, TypeFocus, uses the problematic Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) assessment. Yet even more alarming is how it represents a cultural bias against the value of the humanities and religious studies.

Image note: Moravian transitioned from a College to a University in the summer of 2021, but the software has yet to reflect that change.

The software is also used by Briar Cliff University, Tennessee Tech University, University of Detroit Mercy, York Technical College, Eastern Kentucky University, Washtenaw Community College, and more. The first of three sections of the TypeFocus assessment is a modified version of the MBTI assessment, and asks students to respond to 62 prompts by selecting one of two choices. (Example items: Pick the option that best describes you: 1) tender or 2) objective?; Which option do you find more appealing: 1) by yourself or 2) with others?). The questions offer no context and limit respondents to dichotomous answer choices, meaning that there is no option for expressing that “it depends.”