White Supremacy in the Classroom

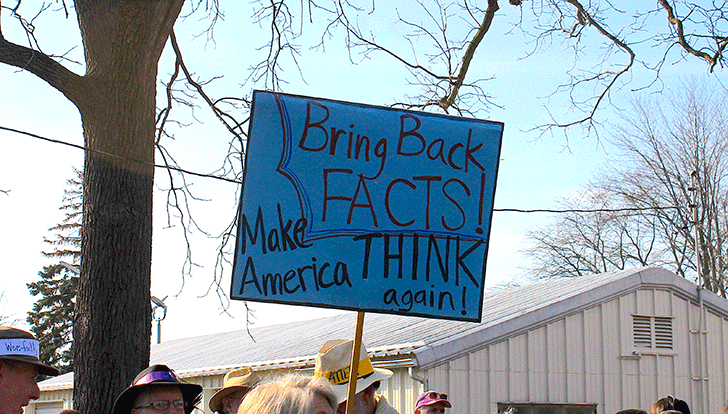

Photo: Women’s March in Seneca Falls, NY, on Jan 21, 2017, by Lindy Glennon.

Teaching Strategy

One way to facilitate honest conversations about contemporary white supremacy and privilege in the religious studies classroom is to examine and challenge the racial scripts of color-blind racism. To this end, I use Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s (2013) Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America at the conclusion of my course on religion in the modern civil rights movement. It has proven to be an excellent text to illuminate the shifting and persistent nature of white supremacy in post-civil rights America. This color-blind racism is characterized in part by its seemingly non-racial and non-historical approaches, subtle and covert nature, and avoidance of traditional racist discourse; all of which serve to render the enduring mechanisms of racial inequality invisible (26).

Chapter five, “I Didn’t Get that Job Because of a Black Man: Color Blind Racism’s Racial Stories,” is particularly useful in the religious studies classroom. The chapter offers a qualitative examination of a national study concerning how white college students often employ similar racial story lines when confronted with discussions about race. These racial scripts enable white students to make sense in their own mind of race in contemporary America. However, they also function to justify and defend white supremacy. In addition to the use of similar phrases (e.g., “the past is the past,” or “I didn’t own any slaves,” and “I don’t see color,” etc.), these narratives of “defensive belief” also tend to have a religious motif. These racial “testimonies,” as the author calls them, usually take the form of “confession, example, and self-absolution.” The study presents several examples of white students quickly lapsing into first-hand accounts of a racist incident perpetuated by a white person that concludes with the storyteller or perhaps another white person emerging as the redemptive figure or as the real victim of racism. Bonilla-Silva then shows how these patterned testimonies, while often well meaning, actual reify racial subordination. Indeed, this “rhetorical arsenal” of racial testimony renders racism as primarily a problem of personal interactions or a burden that primarily harms white Americans. In the end, these racial scripts all serve to buttress the fable that America is largely a “color-blind” society. If racial inequalities exist, white Americans suffer the most, not people of color. Bonilla-Silva confronts this narrative head-on.

In preparation for this reading, the class reads George Lipsitz’s (2006) “Law and Order: Civil Rights Laws and White Privilege,” in his The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics. The brief chapter examines how massive white opposition to major civil rights legislation has enabled the persistence of structural and institutional white supremacy. Armed with this perspective, students read chapter five of the Bonilla-Silva text and gain a better understanding of how racial storylines hinder us from seeing the mechanisms and structures responsible for the perpetuation of white supremacy and racial inequality in contemporary society.

I have my students sit in a circle and discuss the Bonilla-Silva chapter near the conclusion of the course. The exercise has yielded fruitful and honest discussion on the topic at hand. The students are paired with the person seated next to them. They are then assigned to discuss one college student from the text with their partner and share why they chose the particular student. Following this discussion, we reconvene as a whole class. Students then share their discussions to the entire circle. In my experience, white students have been quick to speak about their identification with the college students in the text. They have continually attested to the realization that their own well-intentioned racial scripts do indeed perform sociological work in daily life. Several have acknowledged how their daily testimonies have blinded them to their privilege, even as it has dismissed the subjugation of people of color.

To this end, several students of color have engaged the conversation. They have touched upon which racial testimonies they have encountered the most, both in life and on campus. Moreover, they have continually divulged how these testimonies have discounted their experiences of white supremacy. Usually without my aid, the discussion has often then turned to how the white students and students of color might have more fruitful and honest discussions about racism in contemporary America, authentic dialogues that move beyond racial storylines and help white students discuss race without falling prey to the testimonial formula of “confession, example, and self-absolution.”

The text works well even in the case of students feeling reticent about sharing their own feelings. The chapter’s focus on real college students allows for students to engage actors their own age. Therefore, even if students do not share, reflecting on the text still allows for a substantive discussion. Regardless, this class session has continually yielded very honest and helpful class discussions. Indeed, at the conclusion of one semester, I was informed that several students formed a reading group to read Bonilla-Silva book in its entirety.

Background and Theory

I decided to use Bonilla-Silva text on account of experiencing difficulty in structuring truthful and honest classroom conversations about white supremacy in contemporary America. I teach undergraduate courses on the history of the 20th century American religious experience. I often examine race and religion in the past. This certainly allows for both scholarly and critical distance, which often yields productive insights into the nature of white supremacy in the nation’s history. However, narratives of religion and Jim Crow can also easily morph into stories of the inevitability of American racial progress. Such historical events can condition students to misunderstand change over time and its relationship to the persistence of white supremacy. Indeed, the power, courage, and mythology of the religious crusades of the civil rights movement leads some of my students specifically, and Americans more broadly, to believe that white supremacy was completely exorcised from the soul of the nation. Racial inequalities in contemporary America then are viewed as the result of personal failure, not enduring systemic racial inequality.

This triumphant narrative—not to mention the fact that the first black President was the first president of college students’ teenage and adult years—can actually prevent honest and productive dialogue about the contemporary nature of racial inequalities in America. Indeed, despite the profound changes to America’s racial customs following the civil rights movement, a new racial structure has emerged, enabling the continuance of certain forms of white supremacy and racialized inequality. This “color-blind racism” has no regard for the strong and persistent white opposition and weakening of civil rights legislation. Racism is deemed dead. There is, therefore, no need to remain vigilant against racist practices and institutions, despite blatant racial inequality. As Chief Justice Roberts announced from the highest court in the land during a 2007 school desegregation case, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race, is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” This is, in part, the challenge of talking about white supremacy and racial inequality in contemporary America: we are constantly told that we live in a “post-racial” society even as racial inequalities persist.

Derald Wing Sue’s (2015) book Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence: Understanding and Facilitating Difficult Dialogues on Race is very helpful in thinking about how to approach discussions about race in a post-racial society. Sue encourages a pedagogy that aims, in part, to identify and examine racial biases and racial narratives that render white supremacy invisible. Once these scripts are named and their veneer of neutrality is removed, frank and fruitful discussion can occur. Moreover, we can then remain vigilant against such racial narratives. My search for texts that would facilitate such frank research-based dialogue among college students led me to Bonilla-Silva work.

Conclusions and Extensions

Pedagogy that focuses on racial narratives has important implications for teaching and learning in religious studies in the age of color-blind racism. First, it allows us to see the importance of examining past and present constructions of whiteness in religious studies. Narratives of whiteness are more than just stories. Rather, they are rituals. These rituals shape and affirm worldviews. They uphold that which is considered sacred, valuable, and good: whiteness. Naming and studying the ritualization of whiteness can help discussions about race and religion be more honest and fruitful.

Second, interrogating these narratives in religious studies classrooms can de-center whiteness in the study and teaching of religion. As Marla Frederick has written, in the study of American religion, whiteness has operated as a normative category, while the study of people of color is subsumed under various categories (e.g., African American religion, etc.) Naming and examining whiteness as a socially constructed ritual can not only aid discussions about race, it can also help us rethink the kinds of texts and assignments we give our students when we teach courses on the “American” religious experience.

Finally, examining the racial narratives of college students can aid white students in doing their own racial work. Too often the burden of classroom discussions on race are laid on the shoulders of students of color. Focusing on color-blind racial scripts can encourage white teachers and leaders to engage in self-examination. Indeed, for it is the practice of self-reflection that is a key component to the teaching and learning experience.

In light of the recent election, such honest and informed conversations and reflections on racism and white supremacy are a must. Our classrooms must better equip our students, of all races, to engage in pressing public conversations that epitomize color-blind racism. White supremacist groups and think tanks continue to align themselves with and champion “mainstream” politicians, respectable publications, and causes. However, they are increasingly eschewing the label “white supremacist” or “white nationalists.” Instead, they are associating under the banner of “populists,” “identitarians,” and/or “alternative/alt-right.” Their aim, they argue, is not racist. Rather they simply want to maintain and buttress white identity. As such inflicted rhetoric is increasingly heard from the Supreme Court, White House, and Congress, our classrooms must help our students understand how such racial narratives are not harmless, irrelevant, or aberrations in the American experience. They are the foundation of America’s new racial structure: color-blind racism.

Resources

Baker, Kelly. 2011. Gospel according to the Klan: The KKK’s Appeal to Protestant America, 1915–1930. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Dupont, Carolyn Renée. Mississippi Praying Southern White Evangelicals and the Civil Rights Movement, 1945–1975. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Kruse, Kevin Michael. 2005. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lipsitz, George. 2006 “Law and Order: Civil Rights Laws and White Privilege.” In The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Marsh, Charles. 1997. God’s Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2013. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America, 4th edition. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Silver, Christopher. 1997. “The Racial Origins of Zoning In American Cities.” In Urban Planning and the African American Community: In the Shadows, edited by June Manning Thomas and Marsha Ritzdorf. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Steele, Claude M. 2010. Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Sue, Derald Wing. 2016. Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence: Understanding and Facilitating Difficult Dialogues on Race, 1st edition. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Sugrue, Thomas J. 1996. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lerone A. Martin is assistant professor of religion and politics in the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in Saint Louis. He is the author of the award-winning Preaching on Wax: The Phonograph and the Making of Modern African American Religion (New York University Press, 2014), the 2015 recipient of the prestigious Frank S. and Elizabeth Prize for outstanding scholarship in religious history by a first-time author by the American Society of Church History. In support of his research, Martin has received a number of national fellowships, including the American Council of Learned Societies and the Louisville Institute for the Study of American Religion. He currently chairs the American Academy of Religion Committee on Teaching and Learning and serves as cochair of the Afro-American Religious History Program Unit. Currently he is researching the relationship between religion and national security in American history.

Lerone A. Martin is assistant professor of religion and politics in the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in Saint Louis. He is the author of the award-winning Preaching on Wax: The Phonograph and the Making of Modern African American Religion (New York University Press, 2014), the 2015 recipient of the prestigious Frank S. and Elizabeth Prize for outstanding scholarship in religious history by a first-time author by the American Society of Church History. In support of his research, Martin has received a number of national fellowships, including the American Council of Learned Societies and the Louisville Institute for the Study of American Religion. He currently chairs the American Academy of Religion Committee on Teaching and Learning and serves as cochair of the Afro-American Religious History Program Unit. Currently he is researching the relationship between religion and national security in American history.