“Even Trump has Buddha-Nature” and “Trump as Lord Vishnu”: Teaching Buddhism and Hinduism in America as Critical Pedagogy

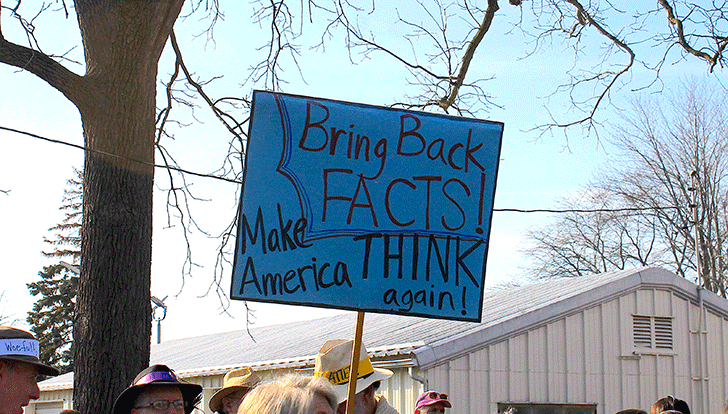

Photo: Women’s March in Seneca Falls, NY, on Jan 21, 2017, by Lindy Glennon.

I was in Indonesia, attending the fourth annual conference of the International Association of Theravada Buddhist Universities when the election results came in. Being so far away in an unfamiliar place, made me feel all the more forlorn, and I was desperate to share my grief. So when I met an American at the conference, the first thing I blurted out was “Oh my gosh, are you devastated?”

The question was rhetorical so I was shocked when she replied, with very little affect, “Not at all.” In response, perhaps, to my look of bewilderment, she continued, “It’s just another impermanent arising in the wheel of samsara, isn’t it?”

My surprise turned to suspicion, however, when I discovered she was part of a Burmese contingent of monks, some of whom, the evening before, had dismissed my questions about Buddhist violence towards the minority Rohingya Muslims with the claim that it was “just the media” making something out of nothing. Was her lack of concern primarily a sign of Buddhist piety, I wondered, or a reflection of anti-Muslim Buddhist nationalism in Burma?

Later at a panel on the social relevance of Buddhism, another incident on a similar note jarred me. A junior female scholar delivered a thoughtful paper on interreligious dialogue in Indonesia, interweaving reflections of her own struggles to integrate her growing interest in Buddhism with her Muslim upbringing. The patronizing response of the senior monastic present not only managed to reduce a sophisticated autoethnographic paper to a narrative of self-discovery but also included a dig at attempts to reestablish the Theravada female bhikkuni lineage by claiming it was in tension with the teachings of anatta or no-self. I was livid! Would this monk be as quick to employ metaphysical doctrine to dismiss identity if his own agency and authority were in question? After all, on meeting me earlier, he had given me a biographical pamphlet, which detailed his numerous prestigious achievements from his early schooling to present monastic life. Where was his concern with no-self, then?

I returned to Florida with a heart weighed down by the global rise of religious nationalism, Islamophobia, and the employment of religious doctrines to erase the concerns of vulnerable populations and reinforce dominant, oppressive structures of power and privilege. All of these have been prominent features of the pre- and post-election North American landscape. As well reported, 81% of white evangelicals voted for a candidate who based his campaign largely on white ethno-nationalist populism, Islamophobia, racism, and misogyny. While some evangelical women denounced Trump’s bragging about sexual abuse, male evangelical leaders rushed to deliver theological apologetic defenses. David Brody, correspondent for the Christian Broadcasting Network, for example, tweeted “This just in: Donald Trump is a flawed man! We ALL sin every single day. What if we had a ‘hot mic’ around each one of us all the time?” Scholars of American Christianity have produced potent critical analyses of this religious-nationalist landscape as well as useful pedagogical reflections on how to approach these topics in the religious studies classroom. Inspired by critical and feminist pedagogies, I will suggest ways by which scholars of Asian religions in America might promote critical thinking around these issues in their syllabi.

Trump as Lord Vishnu? Hinduism in America as Critical Pedagogy

The history of Asian religions in America provides no shortage of material to situate the present Islamophobic and anti-immigrant climate. The discrimination and violence faced in the late 19th and mid-20th century by Chinese and Japanese immigrants shows that American Muslims are the latest victims of a long history of anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States. After being invited to come and work in the California Gold Rush, Chinese, Japanese, and Indian immigrants successively found themselves the target of rhetorical and physical violence from white nationalist organizations such as the Asiatic Exclusion League as well as subject to a series of legal discriminations that culminated in the 1924 Asian Exclusion Act. The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II stands as a shameful reminder of how whole groups of Americans were stigmatized and incarcerated under a national climate of xenophobia. I explore this history through discussion-based lectures with close analyses of primary documents, images, and documentary clips.

Many prominent Japanese American Buddhists such as George Takei have spoken out against the proposed Muslim registry. To show how this issue cuts across religious traditions, I have incorporated material produced by the Blaine Memorial United Methodist Church in Seattle to mark the 75th Anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066 of 1942. Reverend Derek Nakano, the pastor of the church, asked his parishioners to share their own internment stories in support of immigrants and refugees. I have also included the Japanese-Muslim solidarity campaign #VigilantLove and images such as the tweeted photograph of a young boy holding a sign declaring, “Japanese Americans Against Muslim registry,’ that went viral during the Women’s March on Washington.

These solidarity images and narratives function as nice segue to the South-Asian American immigrant experience. Over two classes structured around short lectures, class discussion, and analysis of Internet and multimedia clips, we unpack the analytical components of Vijay’s Prashad’s (2001) The Karma of Brown Folk. Building on W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1903 classic sociological text The Soul of Black Folk, Prashad argues that whereas African Americans have been constituted as “the problem” minority, Asian Americans have been constituted as “the solution” minority and used “as a weapon in the war against black America.” He explores the multiple ways in which American Hindus have internalized the “model minority” myth and perpetuated racism through their identification with whiteness as well as being subject themselves to violence and discrimination. One chapter, for example, focuses on “Yankee Hindutva,” and the devastating consequences of the construction of an essentialist and ahistoric Hindu identity for women and American Muslim and African American minorities.

This semester I use American Hindu responses to Trump as the primary material to read alongside the Karma of Brown Folk. The Republican Hindu Coalition (RHC) support for Trump shows parallels between Hindu and Christian religious ethno-nationalism and the internalization of the model minority framework. Take, for example, “The Hindus for Trump” Facebook page description: “American Hindus are model citizens, educated and industrious…” with its accompanying image of Trump meditating in a red, white, and blue lotus. Not all American Hindus have been thrilled by Trump replacing Lord Vishnu, however. The Alliance for Justice and Accountability (AJA), a coalition of progressive South Asian groups, launched a counter campaign, #SouthAsiansDumpTrump, to denounce the anti-Muslim sentiments of the RHC.

We consider how American Hindu responses to the racist murder of Srinivas Kuchibhotla in Kansas illustrate Prashad’s analysis. For example, the Telagnana American Telugu Association’s (TATA) suggestion to American Hindus to only speak English in public places demonstrates the public/private split in which South Asian immigrants assimilate in the public sphere and confine their cultural and religious identity in the home. We look at the irony of Hindu Samhati president Tapan Gosh response for Hindus to wear the tilak and bindi for safety; in light of the Dotbusters hate group that was active in New Jersey in the 1980s and responsible for multiple acts of brutal violence against American Hindus; and we consider alternative responses of solidarity such as the #ModelMinorityMutinty and #AsiansforBlackLives, which illustrate Prashad’s call for South Asians to join in solidarity with other minorities as an aspiration and promise, “crafted on the basis of commonalities and differences.”

Even Trump has Buddha-Nature? Buddhism in America as Critical Pedagogy

I find much of the work involved in teaching Buddhism to my undergraduate students in Florida to revolve around the dismantling of their romantic and idealized notions of Buddhism as a transcendent philosophy focused on meditation and world peace. I begin with Donald S. Lopez’s and Robert E. Bushwell’s (2014) short but potent “10 Misperceptions of Buddhism,” and have students identify the two that most surprised them. Unfailingly, they identify “All Buddhists Meditate” as the most shocking with “All Buddhists are Pacifists” and “All Buddhist are Vegetarians” as close competitors for second place. Current events provide Buddhist scholars with ample opportunity then, not only to raise critical awareness, but also to tackle some of the biggest misperceptions hindering our object of study. As a scholar of American Buddhism, I leave Burmese Buddhist nationalist violence aside and focus on how American Buddhist convert responses to the election put pressure on the privileging of meditation in the Western imaginary.

The class is structured around a threefold sequence of examining normative Buddhist perspectives, socio-political Buddhist critiques, and constructivist engaged Buddhist responses. First, students read the Lion’s Roar e-publication “After the Election: Buddhist Wisdom for Hope and Healing,” which features post-election reflections from popular Buddhist teachers in the United States. I put them into pairs and ask them to identify the main Buddhist doctrines drawn upon and how such reflections might translate on a social level. Next, we discuss Pablo Das’s “Why this gay Buddhist teacher is dubious about Buddhist refuge in the Trump Era,” in which he problematizes these responses as reflective of a privileged social location that negates the traumatic reality of marginalized communities. Das suggests that meditation practice and calls to “sit with what is” are not sufficient to create safety for vulnerable populations. He warns against using Buddhist teachings on impermanence, equanimity, and anger to dismiss the realities of such groups and calls instead for the creation of safe spaces inside Buddhist communities and support of social justice organizations as part of Buddhist practices of generosity. Finally, we look at Against the Stream’s (ATS) “Statement of Commitment” as a constructivist American Buddhist response to Das’s call. This statement declares that ATS is not “content to sit quietly” while the civil liberties of fellow Americans are under threat and advocates for specific rights of vulnerable populations framed as expressions of Buddhist teachings on wisdom and compassion.

This sequence aims to show that while there might be universal religious doctrines, there are no universal religious subjects: everyone is situated in a particular socio-cultural location marked by various degrees of privilege and this location mediates and shapes religious discourse. Hence, seemingly “universal” or politically neutral Buddhist teachings such as right speech, equanimity, and meditation can function in reactionary ways to mask and reproduce dominant structures of power. Taken together, these apply pressure to students’ naïve misperceptions of Buddhism as a transcendent, meditative “philosophy” and recover it as a religious tradition fully embedded in and enacted through specific sociocultural and political contexts.

Critical Pedagogy for What to Teach

The above exercises are inspired by critical pedagogy, an approach that aims to translate the insights of critical theory into social justice-oriented teaching practices. Brazilian social theorist Paolo Freire’s (1968) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, the seminal text in this pedagogical lineage, describes it as a means to make visible and transform inequitable and oppressive forms of power. Its aim is to develop learners who are able to critically reflect on their own and others’ particular social-cultural situatedness and participate in the creation of just and equitable societies. In examining certain systems of belief, therefore, critical pedagogy shifts the focus from questions of truth to questions of power, with inquires such as: what populations does this belief system benefit and serve most? Critical pedagogy also emphasizes the collective, structural experience of individuals and is concerned with promoting solidarity between marginalized groups. Nancy Ares (2006) highlights the empathetic dimensions of critical or “transformative” pedagogy, which involves helping students recognize and challenge oppressive conditions in society not only for themselves, but for other vulnerable populations.

Critical Pedagogy for How to Teach

As well as what to teach, another question weighing heavily on many of us now is how to teach? One of the prompts for this edition of Spotlight was whether it was possible or admissible to maintain a stance of neutrality and objectivity when moderating discussions around the post-election landscape. Here feminist pedagogies, close cousins to Fiera’s critical pedagogy, can inform us. Feminist philosopher Alison Jaggar (2013) argues that the goal of being a “dispassionate investigator” governed solely by reason and logic simply confirms the “epistemic authority of the currently dominant groups.” Following Jaggar, I suggest that the goal of being a “dispassionate facilitator”—far from being neutral or objective—simply confirms the authority of the current dominant regime. As feminist pedagogy has shown, there is no “view from nowhere,” and, quite frankly, as a queer, gender nonconforming professor, I feel that it would generate more suspicion and distrust from students if I pretended I did not have strong ethical commitments around these issues.

Moreover, a goal of dispassionate facilitation assumes there are no real power differentials between views, and it risks injury to our most vulnerable students. While maintaining the classroom as a space for a diversity of views, I suggest tackling head-on the hijacking of liberal diversity discourse and promotion of false equivalencies that has been employed to chilling effect in the so called “alt-right.” Consider the language employed in the White Student Union Facebook groups that sprung up as a backlash to Black Lives Matter in November 2015—these groups claimed to be “providing safe spaces for white students” and to represent a “countervailing voice against intolerance.” Comments on the White Student Union at UCF page showed that many participants could not differentiate between white supremacist groups and ethnic minority student groups. As educators, it is our responsibility to help our students think historically and critically about how social and cultural differences are constituted by various forms of power and privilege and are not equivalent and simply interchangeable.

To do this type of challenging intellectual and emotional work I have found it essential to develop relationships with students, particularly with those whose worldviews are under interrogation. I do this in a variety of ways through intentional interpersonal contact and presenting material in a decentered, transparent personal style. I have found that strategically using personal disclosure is an effective way to build rapport with students and also to help them relate individual experience to structural realities, a move many students seem to struggle with. For instance, I share my own experience of being a working-class, first-generation undergraduate student in a prestigious or “posh” university in the United Kingdom and how much anxiety and shame I experienced about things I felt marked me as “less than” my predominantly upper-middle-class peers such as my strong regional accent. Because my accent is one of the things that American students tend to find very endearing about me, it works really well as a personalized “way in” to think about class, social mobility, and different types of access and belonging. I also share my own ethical failures such as an experience I had when I did not sufficiently challenge a racist, anti-immigrant comment made by another white female passenger on a flight to the United Kingdom from Morocco. Many students can be extremely defensive around issues of race, and I have found that a little humility and vulnerability (“I got that wrong too”) can go a long way in defusing that defensiveness so that attention and energy can be focused on the most effective ways to recognize and combat discrimination (“So how can we get that right?”).

In short, I have found that if students feel seen and have some sense of emotional rapport, or as one of my students put it, that we are talking to them and not at them, they can tolerate more discomfort and pressure on their worldviews. Rather than be preoccupied by objectivity, then, I suggest we focus on how to build genuine affective relationships with and between students, relationships marked by trust and resilience that can best support uncomfortable, challenging but absolutely necessary conversations about difference, racism, white privilege, and Islamophobia.

Resources

“A Guide to Feminist Pedagogy.” 2015. Vanderbilt Center for Teaching. Last accessed May 22, 2017. https://my.vanderbilt.edu/femped/habits-of-head/the-role-of-experience-emotions/.

Bushwell, Robert E., Jr., and Donald S. Lopez Jr. 2014. “Ten Misconceptions about Buddhism,” Tricycle Summer. Last accessed May 22, 2017. https://tricycle.org/magazine/10-misconceptions-about-buddhism/.

Ares, Nancy. 2006. “Political Aims and Classroom Dynamics: Generative Processes in Classroom Communities.” Radical Pedagogy 8 (2) 12–20.

Das, Pablo, 2016. “Why this gay Buddhist is dubious about Buddhist Refuge in the Trump Era.” November 17 Lion’s Roar https://www.lionsroar.com/commentary-why-this-gay-buddhist-teacher-is-dubious-about-buddhist-refuge-in-the-trump-era/

Freire, Paulo. 2000 (1968). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

Freire, Paulo, Ana Maria Araujo Freire, and Walter de Oliveira. 2014. Pedagogy of Solidarity. London, UK: Routledge.

Jaggar, Alison M. 2013. “Love and Knowledge: Emotion in Feminist Epistemology.” In Feminist Theory Reader: Local and Global Perspectives, 3rd edition, edited by Carole McCann and Seung-kyung Kim, 486–501. New York, NY: Routledge.

Prashad, Vijay. 2001. The Karma of Brown Folk. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Sperry, Rod Meade. 2017. “Not Content to Sit Quietly: The Meaning and Making of Against the Stream’s new ‘Commitment Statement’.” Lion’s Roar. February 28. Last accessed May 22, 2017. https://www.lionsroar.com/not-content-to-sit-quietly-the-meaning-making-of-against-the-streams-new-commitment-statement/.

Tweed, Thomas A., and Prothero, Stephen, eds. 1998. Asian Religions in America: A Documentary History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Ann Gleig is assistant professor of religion and cultural studies at the University of Central Florida, the second largest public university in the United States. Her main research areas are Asian religions in America and religion and psychoanalysis. She teaches a number of face-to-face and online courses, all of which address various dimensions of the modernization and Americanization of Asian contemplative traditions. She is committed to feminist, critical, and contemplative pedagogies that foster critical thinkers and ethical citizens in the era of neoliberal education. She is the coauthor with Lola Williamson of Homegrown Gurus: From Hinduism in America to American Hinduism (SUNY Press, 2013) and is currently finishing her first monograph on recent developments in Buddhism in American under advance contract with Yale University Press.

Ann Gleig is assistant professor of religion and cultural studies at the University of Central Florida, the second largest public university in the United States. Her main research areas are Asian religions in America and religion and psychoanalysis. She teaches a number of face-to-face and online courses, all of which address various dimensions of the modernization and Americanization of Asian contemplative traditions. She is committed to feminist, critical, and contemplative pedagogies that foster critical thinkers and ethical citizens in the era of neoliberal education. She is the coauthor with Lola Williamson of Homegrown Gurus: From Hinduism in America to American Hinduism (SUNY Press, 2013) and is currently finishing her first monograph on recent developments in Buddhism in American under advance contract with Yale University Press.