The 2016 Election and its Aftermath in the Religious Studies Classroom

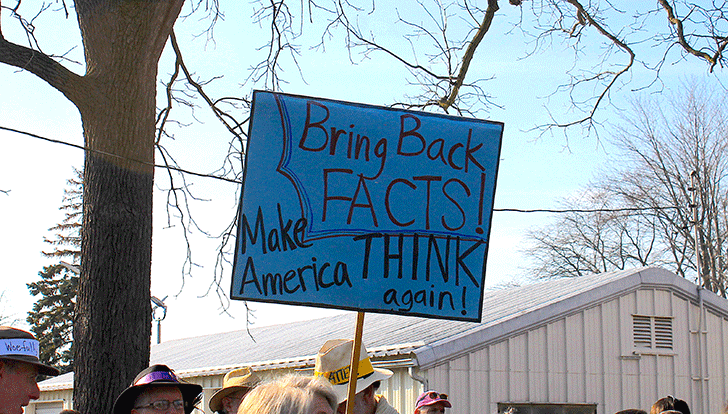

Photo:Women’s March in Seneca Falls, NY, on Jan 21, 2017, by Lindy Glennon.

The impact of the 2016 election of Donald J. Trump as 45th President of the United States reverberated across campuses all over the country, affecting students and their professors in religious studies classrooms in myriad ways. In the immediate aftermath of the election, teachers faced emotionally charged classrooms, replete with students who were weeping and despondent, terrified and stunned, elated and vindicated, and the full-range between. Walking into the classroom bleary-eyed the morning after the election raised immediate pedagogical questions for those of us standing in front of students in the throes of processing the results. Should we initiate a discussion about students’ reactions or avoid addressing it head-on given the emotional intensity of the moment? Should we stick tightly to the scheduled topic of the day, or veer off the syllabus to consider what was, to many, a shocking election outcome? Should we maintain a neutral stance in the classroom, giving all students’ voices a chance to be heard while maintaining our own objectivity? Or was that even possible, let alone morally conscionable, in the face of rhetoric (not to mention the specter of impending legislation) that left some students and their families endangered?

As the weeks and months since the election have passed, questions persist about the best strategies for teaching students to critically appraise not only the election itself, but also the hate speech, Islamophobia, white supremacy, anti-Semitism, misogyny, and more that has accompanied it. The authors of the essays collected here share their experiences and methods contending with these topics in religious studies classrooms located all over the country—in blue states (Bazzano and Glennon in New York; Trelstad in Washington), red states (Shearer in Montana; Martin in Missouri; Glass-Coffin in Utah), and one swing state (Gleig in Florida)—each specialized in different religious studies subfields. They hail from large state universities (Gleig; Shearer; Glass-Coffin); large private universities (Martin); and religiously affiliated colleges (Bazzano; Glennon) and universities (Trelstad).

The editors posed the following questions as guideposts for authors’ contributions:

- How have you addressed the US presidential election and its aftermath in the religious studies classroom?

- How can religious studies scholars best teach and mentor students experiencing terror, grief, and uncertainty in the face of the rise of the alt-right/white nationalism and the prospect of a Muslim registry and mass deportation of undocumented immigrants?

- Is it possible or even admissible to maintain a stance of neutrality in the classroom when moderating discussions about politics and the election, allowing all students to voice their viewpoints, including those that may be hurtful or threatening to others?

- If the result of the election is an indictment of the academy, as Cornel West proclaimed at the November 2016 American Academy of Religion meeting in San Antonio, how can our work in the classroom help to redress this?

- What specific teaching methods, classroom discussion formats, readings, and student assignments have you found to be effective tools to enhance student learning about issues related to the causes and consequences of the election of Donald Trump as president?

Tobin Miller Shearer brings his expertise in the history of race and religion in the United States to bear on the problem of how to discuss controversial topics in the classroom. He explains his decision, amid the raw emotion his students expressed on the morning after the election, to forego his typical classroom discussions based on the values of mutual respect, avoiding stereotypes, and grounding comments in evidence and first-hand experience in favor of storytelling. Beyond storytelling, Shearer describes his classroom techniques for dealing with conflict as ones in which he models a “nonanxious presence” as a means to de-escalate conflict. Drawing on the disciplines of mediation and conflict resolution, he engages students with diverse political leanings in discussions that “counter rhetorical bullying” and “invite respectful disagreement,” thus furthering what he argues is a unique role that religious studies scholars can play in “nurturing democracy at a point when it was most threatened.”

Elliott Bazzano considers ways that Islamic studies professors can react to the Trump administration, “with special attention to building positive narratives in addition to challenging existing ones.” He urges that educating college students on what Islam is, and isn’t, is especially crucial now given the rampant Islamophobia that characterizes the Trump White House, for in Trump’s own words, “Islam hates us.” At the same time, Bazzano reflects on a conundrum: even as important as Islam-focused courses are to understanding international politics, following every relevant headline in class quickly dominates course content, leaving little room for anything else. He suggests that equipping students to understand the roots of Islamophobia requires attention to the roots of Islamic traditions, including their aesthetic and intellectual dimensions, not only attention to the latest news cycle’s anti-Muslim vitriol. Bazzano perceives his pedagogical task to be teaching students to think deeply and build narratives, not only critique existing ones, as well as “teaching students skills for understanding the spectrum of the beautiful and grotesque, as this spectrum relates to religion and beyond.”

A specialist in religion and politics in the United States, Lerone Martin describes his approach in a class on religion in the modern civil rights movement to examining the racial scripts that contribute to an assumption that “America is largely a ‘color-blind’ society.” After structuring his classes on this challenging topic by pairing students together to discuss specific aspects of the readings, Martin finds that these discussions help foster authentic dialogues about racism in contemporary America between white students and students of color. In his course about the history of 20th century American religious experience, he inspires students to reconsider “the inevitability of American racial progress,” a narrative especially in need of rethinking in light of the recent election. Martin calls our attention to the importance of pedagogy that focuses on racial narratives as a means to examine constructions of whiteness in religious studies, as well as to examine the racial inequalities that lie beneath the illusion of America as a “post-racial” society.

Ann Gleig teaches the history of Asian religions in America, and she finds much within this history to contextualize “the present Islamophobic and anti-immigrant climate.” She describes her approach to teaching Hinduism in America as one in which she juxtaposes divergent materials, such as American Hindu responses to Trump with scholarship critiquing the presentation of South Asians as model minorities. In her “Buddhism in America” course, she examines American Buddhist convert responses to the election and problematizes these by reading critiques that the convert-Buddhist emphasis on “sitting with what is” in meditation is not sufficient in the face of threats to Americans’ civil liberties. Gleig draws on Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed to explain her teaching methods in these courses as “critical pedagogy,” which she defines as “an approach that aims to translate the insights of critical theory into social justice oriented teaching practices.” She advocates “shifting the focus from questions of truth to questions of power” and working toward “promoting solidarity between marginalized groups.” Gleig invokes feminist pedagogies such as that of Alison Jaggar to conclude that the goal of being a neutral discussion facilitator “simply confirms the authority of the current dominant regime.” She advocates, instead, building “genuine affective relationships with and between students.”

A Lutheran theologian, Marit Trelstad recounts how the 2016 election changed her teaching of Luther. She recounts how she brought Luther’s 1543 writing titled “On the Jews and Their Lies” into a classroom discussion on hate speech by pairing it with contemporary writings on genocide and asking students to list words, policies, and patterns from these disparate sources. In doing this, her pedagogical goal is to move students from passively observing Luther’s historical anti-Semitism to considering the ways in which Nazi Germany actualized aspects of Luther’s rhetoric. She then asks them to apply their critical attention to contemporary hate speech and its effects. She calls students to examine the psychology and rhetoric of genocide and dehumanization that hate speech can invoke, aiming “to offer students tools or signs that may indicate dangerous rhetoric and policy directions such that we do not recommit the errors of Luther that we so openly despise.”

Bonnie Glass-Coffin approaches the topic of teaching about the election and its aftermath from a different perspective, as a professor of anthropology who is an affiliate professor of religious studies and the founder and director of the Interfaith Initiative at Utah State University. She shares a pedagogical approach she has found useful in facilitating interfaith dialogues among students called “speed-faithing.” This is an ice-breaker activity in which pairs of students have two minutes each to respond to a facilitator’s questions about their name’s origins, religious traditions, and values, before switching conversation partners and repeating the process. Inspired by Eboo Patel’s Interfaith Youth Core, which seeks to “make interfaith cooperation a social norm,” part of Glass-Coffin’s mission is to cultivate “authentic sharing, appreciative listening, and meaningful dialogue” as pillars of empathy and connection. She notes that the rationale behind constructing an interfaith dialogue around students sharing their personal religious commitments and values is anathema to the “decades-old wisdom” that students should check their religious commitments at the door when entering the religious studies classroom. Glass-Coffin resists this, suggesting instead that in the postelection campus climate in which hate speech is on the rise, we need “to provide our students with the skills that will bridge difference and cultivate positive relationships across religious divides.”

Fred Glennon is a specialist in religion, social ethics, and society. He shares his experiences teaching about religious, social, political, and economic issues raised by the Trump election in two courses he taught this year: “Church and State” and “Ethics from the Perspective of the Oppressed.” He describes three classroom strategies that have helped him guide discussions in these classes on the aftermath of the Trump election. The first is prompting his students to create what he terms a “class covenant” at the beginning of his courses by posing questions to them about how they feel they should treat one another, respect each other’s opinions, and handle disagreements. Once students have devised their own covenant, he “ritualizes” it by having students pledge the covenant to each other, and he makes it their responsibility, not his, to hold each other accountable to it. The second pedagogical strategy Glennon proposes is teaching with “case studies” in his courses, thereby providing specific examples of real-world tests of issues such as the boundary between religion and government in the United States. Glennon terms his third pedagogical strategy “experiential learning,” which includes exercises such as the “eviction notice” in which Glennon surprises his students by arranging a situation in which they are kicked out of their learning spaces repeatedly by school administrators and must try to continue their classroom activities in public. Glennon finds these techniques useful both for students for and against the Trump Administration and its policies.

The essays collected in this Spotlight issue demonstrate some of the many different approaches religious studies instructors are finding effective in the classroom to teach topics related to the 2016 presidential election and its aftermath. I hope that these insightful essays will further inspire us all to find meaningful ways to foster religious understanding at this time when religious difference is too often demonized in American public discourse.

Sarah Jacoby is an associate professor in the religious studies department at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. She specializes in Tibetan Buddhist studies, with research interests in gender and sexuality, the history of emotions, Tibetan literature, religious auto/biography, Buddhist revelation (gter ma), the history of eastern Tibet, and scholarship of teaching and learning. She is the author of Love and Liberation: Autobiographical Writings of the Tibetan Buddhist Visionary Sera Khandro (Columbia University Press, 2014), coauthor of Buddhism: Introducing the Buddhist Experience (Oxford University Press, 2014), and coeditor of Buddhism Beyond the Monastery: Tantric Practices and their Performers in Tibet and the Himalayas (Brill, 2009). She teaches courses on Buddhism, gender and sexuality studies, and theory and method in the study of religion. She is the cochair of the American Academy of Religion’s Tibetan and Himalayan Religions Program Unit, as well as a member of the Committee on Teaching and Learning.

Sarah Jacoby is an associate professor in the religious studies department at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. She specializes in Tibetan Buddhist studies, with research interests in gender and sexuality, the history of emotions, Tibetan literature, religious auto/biography, Buddhist revelation (gter ma), the history of eastern Tibet, and scholarship of teaching and learning. She is the author of Love and Liberation: Autobiographical Writings of the Tibetan Buddhist Visionary Sera Khandro (Columbia University Press, 2014), coauthor of Buddhism: Introducing the Buddhist Experience (Oxford University Press, 2014), and coeditor of Buddhism Beyond the Monastery: Tantric Practices and their Performers in Tibet and the Himalayas (Brill, 2009). She teaches courses on Buddhism, gender and sexuality studies, and theory and method in the study of religion. She is the cochair of the American Academy of Religion’s Tibetan and Himalayan Religions Program Unit, as well as a member of the Committee on Teaching and Learning.