Hate Speech Red Flags: Recognizing Rhetoric that Justifies Killing, Violence, and Demeaning Others

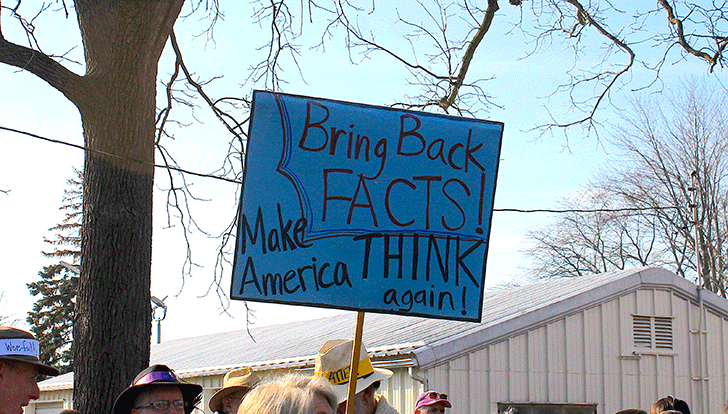

Photo: Women’s March in Seneca Falls, NY, on Jan 21, 2017, by Lindy Glennon.

The 2016 election, the fear of my students, and the rash of hate speech and crimes that rapidly followed, changed my teaching of Luther. It exposed a way to make his abhorrent writing about the Jews useful in a time of demeaning rhetoric. The day after the election, my syllabus dictated that we were to discuss Martin Luther’s 1543 hate speech writing “On the Jews and Their Lies.” But how could we discuss an academic text when students were reporting being called “the ‘n’ word” on campus or being asked when they would be deported? Other students were unaware of the sudden swell of sexism, racism, anti-Semitism, and anti-Muslim rhetoric because they were not the targets. But the surge of hate speech was real, fresh, and extreme.

For teaching Luther after the election, I developed a class session in which we examined Martin Luther’s anti-Semitic rhetoric and recommendations in the assigned treatise. Next we examined Luther using tools provided in the books Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave and Exterminate Others by David Livingstone Smith (2011) and George Tinker’s (1993) Missionary Conquest: The Gospel and Native American Genocide. Smith’s book reveals rhetorical forms and philosophical assumptions in genocidal propaganda of the last century. Tinker’s book on American religious history reveals patterns of cultural genocide toxically embedded within the work of missionaries. The real learning took place by putting the lists of rhetoric, patterns, and policies from all three sources on the board next to one another and then opening it up for discussion.

Throughout the class period, covering Luther, Smith and Tinker, I was struck by the students’ wide eyes and affect of “high alert.” They were engaged and actively evaluating what was happening around us in the news and on our campus. They were interested in tools that might help them analyze the degree to which their fears were justified. I had planned to stop and directly ask about the ways in which Luther, Livingstone Smith, and Tinker elucidated policies and hate speech today. I did not have to. Some students immediately saw connections and offered comments on similarities and differences we were witnessing. At my university, in the polarized red-blue zone of Washington State, the exercises below gave concrete, specific criteria to discuss what constitutes hate speech and how it functions.

Background and Pedagogical Challenges

For a little background, I am a lifelong Lutheran; the church was my second home and I attended a Lutheran college. I was soaked in the message of divine grace and acceptance despite faults. It was not until after college that I had an Aryan Nation pamphlet stuck to my car windshield in Boulder, Colorado, that led with an anti-Semitic quote from Martin Luther. I had never been taught this side of Luther. When I later started teaching Lutheran heritage, I was determined to present the full story of Luther “warts and all.” Luther’s various writings on the Jews, and Lutheran collusion with Hitler in the Second World War, are regular parts of my syllabi. Luther did not believe that human nature got better over time, even with God’s grace. He believed that humans were depraved and sinful and his own theological mix of sunshine and acid evidences this.

Lutheran scholars employ various approaches to work with these awful texts of Luther’s: they acknowledge and denounce them; they distance themselves; they historically contextualize them; they examine Luther’s charismatic and caustic personality. In the classroom, students who had appreciated Luther often walk in disgusted. Frequently, they feel betrayed or duped. Here is a man who was fighting unjust, manipulative power with words of grace—they had just started to like him—and now he is using power and hate against the Jews. I understand their feelings. I reread the text with them each time and feel physically ill. I warn them that they may never read any worse example of hate speech than Luther’s 1543 treatise. Invariably, students struggle to understand the relation between Luther’s violent recommendations of actions to be taken against the Jews and the ones enacted in World War II Germany. They are undeniably similar.

But it has bothered me that reading Luther’s “On the Jews” elicits passive guilt, self-vindication, historical curiosity, or just voyeurism. The text sits inert. Students and others are left judging Luther (appropriately), but the critical lens remains focused there—it does not turn its eye on ourselves or our society. This is partly due to the extremity of his writing which shocked even some of his historical contemporaries.

Passive Guilt Mobilized: The Specifics of the Exercise

Martin Luther

Smith and Tinker’s books provided the tools to examine Luther and our contemporary situation simultaneously. We started with Luther. I had the students highlight and compose lists of the names Luther called the Jews as well as the characteristics and crimes he attributed to them. The students had a hard time saying them out loud, and I had a hard time writing them on the board due to their truly severe offensiveness. But that experience of discomfort was important to the exercise; the list on the board confronted us. Luther uses the following words to describe the Jews whom he is scapegoating: idle, proud, mad, foolish, lazy, usurious, blasphemous against God and country, murderous, raving, greedy, envious. He accuses the Jewish Germans of acting like masters, taking money from “true” or “real” or “rightful” members of the country, kidnapping or harming the well-being of children, poisoning water, and infiltrating society. He argues that Jewish people are acting against “our” religion, which falsely creates the notion of a homogeneous population under “attack” by those within his own country. Throughout the treatise, Luther engages in dramatic name-calling. His exact words are: devils/demons, pigs, whores/sluts, beasts, vipers, wolves, fools, stupid, dogs, evil, thieves, rogues, and adulterers.

To place this in the context of Luther’s work, he describes the leaders of the Church by many of these same names and characteristics—and I point out that we had overlooked it in previous texts when he was speaking to the powerful. No one in class objected then. In his critique of the Church, however, he does not advocate the same actions against the Church as those he offers for the Jewish people. As a class, we named and listed the recommendations he proposes for the Jewish German people: expelling them from the country, razing and burning homes and places of worship, taking over businesses, denying them safe travel, arresting and detaining people in camps and making them work, destroying their sacred books, and displacing and threatening the lives of the leaders and people. In his text, Luther also appeals to a forced and false sense of unified nationalism. Indeed, he helps create the very concept of a unified Germany. We talked about ways this mirrored policies and rhetoric against the Jews in Nazi Germany.

When the students assembled lists of Luther’s name-calling, recommendations, and caricatures on the board, a few audibly muttered, “this sounds familiar.” I asked what they meant and they recounted many incidents of Trump calling specific people and groups names, assigning “dangerous” characteristics to them, during the election. They also recounted the explosion of hate speech since the election. The seemingly positive “Make America Great Again” motto appeared to be supported by ideas that harkened to Luther’s: support for detaining and deportation, economic distress of “real” Americans caused by vulnerable minorities, fear built around infiltration by “outsiders,” and a false homogeneity of race and religion built around scapegoating. It was unsettling to feel connections between Luther’s disgusting tract, the genocide of Jews in the last century, and rhetoric emerging in our own time.

David Livingstone Smith and Dehumanization

David Livingstone Smith’s book specifically examines the psychology and rhetoric of genocide and dehumanization. A particular mindset needs to be established to enable people to mistreat or kill their fellow human beings. When we dehumanize another, it decommissions our inhibitions that would normally prevent our enacting cruelty on others. Through examining propaganda in multiple countries, Smith pulls the common elements of rhetoric (language and imagery) that supported genocide in the past century. In line with Smith, a National Geographic article in 2006 named the last one hundred years as the “century of genocide” due to the unprecedented number of mass murders across the globe. His book reveals that dehumanizing rhetoric, conducive to genocide, equates people to insects, snakes, invasive vermin, and undesirable or predatory animals. It also capitalizes on the assumption that someone’s essential nature is fixed and subhuman (“less than human,” as in the book’s title) despite appearance of humanity. Someone does not just lie. They are a liar. “Subhumanity,” Livingstone Smith writes, “is typically thought to be a permanent condition. Subhumans can’t become humans any more than frogs can become princes” (159).

George Tinker

George Tinker’s book Missionary Conquest, provides another valuable tool as he explains the patterns of actions involved in cultural genocide. He repeatedly assures his reader that missionaries acted with good intentions and yet committed atrocities. He is exceedingly clear that feelings of guilt will not prevent future genocide and oppression. He writes:

The implicit agenda of this book . . . is to raise a critical question for us to consider in our own historical and theological context, namely, What is our blindness today? With the best of intentions and with the full support of our best theologies and intellectual capabilities, do we continue to fall into the same sort of traps and participate in unintended evils? My presupposition is that without confronting and owning our past, as white Americans, as Europeans, as American Indians, as African Americans, and so forth, we cannot hope to overcome that past and generate a constructive, healing process, leading to a world of genuine, mutual respect among peoples, communities, and nations. (viii-ix)

Beyond this, he also reveals patterns of cultural genocide that were repeated in different areas of the Americas. In my class, we focused on these “red flags” (my phrase, not Tinker’s) or patterns of cultural genocide present in Luther’s writing and also perhaps today. Tinker urges his readers to familiarize themselves with these signs so that we pay attention and scrutinize potential larger patterns at work in seemingly discrete actions or policies. He outlines the following four consistent patterns present in physical and cultural genocide:

- Political signs: Threats “to control and subdue a weaker culturally discrete entity” (6).

- Economic signs: “Using and allowing the economic systems, always with political and even military support, to manipulate and exploit another culturally discrete entity that is both politically and economically weaker” (7).

- Religious signs: “Overt attempt[s] to destroy the spiritual solidarity of a people” (7).

- Social signs, including:

- “Obvious attacks on the relationships that bind a community together”

- Breaking up families and communities

- Denial of language or criminalizing religious rituals

- Displacing people from their homes or forced relocation

Conclusions and Extensions

Over the course of the class, we examined Luther’s text and contemporary rhetoric and policy with the criteria of Smith and Tinker in mind: Do we witness incidents of pinning humans with nonhuman names or characteristics? Do we see an attempt to ascribe permanent, bad essences to particular people and groups? Undeniably, Luther’s writing carries these marks of the genocide-supporting propaganda Smith explores. He repeatedly assures his reader that missionaries acted with good intentions and yet committed atrocities.

In terms of today, I could tell they were busy assessing whether the current presidential administration’s rhetoric and policy advocacy met the criteria for genocidal propensities. In a politically and emotionally charged atmosphere, students turned naturally, but cautiously, to applying our learning to the election. They described the persistence of name-calling by both sides in the election but noted that, in the debates, Trump’s rhetoric had untiringly depicted particular groups of people as being threatening, opportunistic, nasty, bad, or dangerous. We discussed how and whether the new Trump administration’s proposed policies were designed in ways that met Tinker’s criteria. All in all, the focus on specific types of language and socio-political patterns gave us concrete things to analyze in a chaotic time; it was a type of evaluative space through which we could navigate discussions.

My goal for the class was to offer students tools or signs that may indicate dangerous rhetoric and policy directions such that we do not recommit the errors of Luther that we so openly despise. Red flags themselves cannot confirm that we are actually dealing with genocidal intentions. Awareness can, however, calls us to analyze the situation and patterns of policies more closely. The work of Livingstone Smith warns that demeaning others is a precondition to greater and more dangerous oppression and thus attention to language is valuable. Tinker identifies the patterns in cultural oppression so that we can recognize them and resist. As scholars, we are committed to representing the material of our field, the content and cannons. But if we are seeking a more aware, humane and just world, we also need to glean tools from our course material in creative ways.

Resources

Luther, Martin. (1543) 1958. "On the Jews and Their Lies." In Luther's Works, The American Edition, vol. 47, eds. George Forell and Helmut Lehmann. Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press.

Smith, David Livingstone. 2011. Less Than Human: Why we Demean, Enslave and Exterminate Others. NY, New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Tinker, George. 1993. Missionary Conquest: The Gospel and Native American Genocide. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press.

Marit A. Trelstad is professor of constructive and Lutheran theologies at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington. Her scholarly work combines feminist, process, and Lutheran theologies and has focused on Christology, theological anthropology, the doctrine of God, and science and religion. As a contributor and editor, she published Cross Examinations: Readings on the Meaning of the Cross Today (Fortress Press, 2006) and contributed chapters to Transformative Lutheran Theologies (Fortress Press, 2010), Lutherrenaissance: Past and Present (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2014), Theologies of Creation: Creatio Ex Nihilo and Its New Rivals (Routledge, 2014), and Creating Women’s Theology: A Movement Engaging Process Thought (Chalice Press, 2011).

Marit A. Trelstad is professor of constructive and Lutheran theologies at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington. Her scholarly work combines feminist, process, and Lutheran theologies and has focused on Christology, theological anthropology, the doctrine of God, and science and religion. As a contributor and editor, she published Cross Examinations: Readings on the Meaning of the Cross Today (Fortress Press, 2006) and contributed chapters to Transformative Lutheran Theologies (Fortress Press, 2010), Lutherrenaissance: Past and Present (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2014), Theologies of Creation: Creatio Ex Nihilo and Its New Rivals (Routledge, 2014), and Creating Women’s Theology: A Movement Engaging Process Thought (Chalice Press, 2011).