Anti-Racism in the Religious Studies Classroom: Compassionate Critique and Community Building

Difficult topics are par for the course in the religious studies classroom. Our object of study, the myriad human behaviors categorized as religion, often spark impassioned debate and disagreement. However, the main pedagogical issues I face in the classroom tend to emerge from the absence, not the abundance, of debate and dialogue. This became even more palpable after the most recent presidential election, as students became reticent to speak about issues like race and religion or any of the contemporary political examples that I wanted to use for class discussion. Candidate Trump’s proposed Muslim Ban, and the later executive orders meant to instantiate it, are excellent examples of the issues we should be talking about in religious studies courses. However, my students had difficulty engaging with these issues, both in class discussions and in response papers.

In order to get students comfortable talking and writing about topics like race, religion, and ethnicity, I quickly learned that it was essential to create a strong classroom community that provided students the space to try out this new material, make mistakes, fail, and recover without feeling disconnected from their classmates. This idea of community soon became central to the development of anti-racist pedagogies in the form and content of my teaching. While I use this technique in other courses, I will focus on my “Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in the US” class as an example. This course is a cross-listed, upper-division seminar with a general education writing component. Thus, it is at once a seminar, a writing workshop, a religious studies class, and a black studies class at my small liberal arts college. Meeting all of the requirements of form and content while dealing with difficult material provides a challenge, and I find that a focus on creating a classroom community helps to reconcile some of these demands.

In a broad sense, anti-racism is both the form and content of the class. The course analyzes the concept of “race” as a category within the field of religious studies. It is not a survey of race in American history; instead, it is an exploration of race in the study of American religion. The aim is for students to begin to recognize the constructive power of the category of race in religious studies scholarship and to begin to construct their own research questions that challenge the paradigms of the field. In essence, we examine the ways in which talking about race can itself be a disruptive act, an anti-racist project. In order to achieve this, community, support, and open discussion in the classroom are necessary.

Teaching Strategies

The first strategy that I use relates to the creation of a strong community. To cultivate learning, the classroom must be a space where students are able to fail, to correct, and to begin again. We start this work the first week of class in a low-stakes form of play. I use an entire day of class to play the board game Taboo, and I have found it is worth the initial time investment. Taboo is a word-guessing game in which two teams compete to correctly guess the most words. Players are given a card with the key word at the top. They then attempt to get their team to guess that word by describing it without using any of the other “taboo” words listed on the card. For example, a player will attempt to get their team to guess the word “lullaby” without using the words baby, sleep, cradle, sing, or rock. If they use the taboo words, another player “buzzes” them, and they have to move on, no points awarded. Taboo works well for many reasons, a primary one being that it is an older game that most of my students have never played. This means that they all have to learn it together. I give them a few rules: they have thirty minutes, they must have two teams, and everyone has to participate. I then place the box in the center of the table and remove myself from the game, and I simply observe. Their task is to play the game.

Taboo works well for community building in a variety of ways. Students have to work together to figure out the rules, everyone has to participate, and there are alternating moments of low-stakes anxiety, laughter, and competition. They also have to speak, guess, correct other players, and struggle to make their points with a limited vocabulary. The most important part of this exercise follows the game. After we finish, I ask students to reflect on what Taboo has in common with classroom discussion. From this we spend the remainder of class developing ground rules for our own discussions. What is taboo for us? How do we engage one another? What do we do when someone needs correction? How do we object without a buzzer? And my students do well with this. They come up with fantastic ideas about how we can speak and listen with respect. I stand at the board and take notes on their brainstorming session, about everything from what kinds of content is useful in discussion (textual evidence? personal experience?) to the responsibility of students to prepare for class by reading so that we have a shared vocabulary. Slowly, a list takes shape.

Together we come up with a set of guidelines that I type up, hand out in hard-copy form, and post to our class website. Ideally, we revisit them several times in the semester. I have consistently found that this type of low-stakes play creates a strong foundation for student interaction in the class. However, it is imperative that the game is contextualized and reflected upon if it is going to be used as a learning tool. This is also a great time for me, as an instructor, to observe the class, learn names, and begin to get to know the students. My seminar classes usually have a maximum of eighteen students, so this activity would have to be adapted for larger classes, though the basic principles of play, participation, and speaking and listening are essential parts of the exercise, whatever game you might choose.

Students definitely feel that there are taboos around the topics of race and religion. This game provides an opportunity for the class to discuss this and decide how to deal with the very real problem of saying something that is offensive or misinformed. In other words, what do we do about racist comments? As this comes up in our brainstorming session, students often have great ideas. They always point out the need to correct misinformation and to educate in cases of ignorance. This is a moment when I offer a few strategies that I want them to use to achieve those goals. The only classroom discussion guidelines that I add to the list (and I bring them up at the end of the session, after they have done most of the heavy lifting), are kindness and honesty. These are the values that inform how we respond to racism in the classroom, a strategy that I call “compassionate correction” or “compassionate critique.” This means listening and giving each other the benefit of the doubt, but also being sure to correct problems. I model this in class, I ask students to do this, and I also remind them that I too, may need to be corrected. We begin to use this language on small things (students have compassionately corrected my spelling on the chalk board) and on more serious issues (when textual interpretations go a bit off the rails, when insensitive comments are made, or when problematic language is used, we compassionately correct each other). Compassionate correction/critique is a way to remain diligent in correcting problematic language and action without slipping into unproductive forms of call-out culture. This creates a space where students are allowed to make mistakes as a part of the learning process, which makes them more receptive to the critiques they receive.

So what does this look like over the course of the semester? We start by having basic discussions about the definitions and descriptions of race and racism, and then move to religion. Our first readings are classic texts on structural racism from Beverly Daniel Tatum and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva. Students are assigned as “experts” on respective readings, and in class they work with other experts, first in small groups to solidify their understanding of the reading, and then as a class to debate the finer points of comparison and contrast between them. I serve as a note-taker at the board while my experts discuss how the concepts are used in the texts, the problems and gaps in the readings, and the things we want to continue to use or discuss as we move forward. Because it is a writing class, we discuss the kinds of evidence and analysis that authors use as well as the ways they organize their arguments. While this may seem like a simple exercise, when race and prejudice are the topics, things go wrong. Students begin right away to use compassionate correction/critique as a way to communicate with kindness. Usually the first example of this comes when students grapple with authors’ assertion that there is no such thing as “reverse racism.” Inevitably some students have difficulty with this; however, with Taboo fresh in their memory, students are quick to use their agreed upon guidelines in discussion. First this comes in the form of measured second-order statements, “I think Tatum would buzz you here…” or “Bonilla-Silva might compassionately correct you there...” Later in the semester, they begin to take more ownership of their own objections, especially when they recognize we are critiquing ideas, not people. Then I begin to hear more active, first-person language, such as “I would compassionately correct the author here…” or “I disagree with this argument because…”

This strategy for creating community in the classroom begins with collective development of guidelines for discussion that include models for interactions and interventions. Just as the form of the classroom is meant to reflect anti-racist pedagogies, the content is as well. To align theory and praxis as anti-racist scholarship, speaking and writing projects are meant to give students practice with description (presenting the work as a discussion leader), analysis (short papers), and application (applying theories to examples outside of the texts). We read examples of contemporary scholarship that highlight how race and religion can be analyzed in ways that recognize and disrupt cultural appropriation, orientalism, racialization of religion, and normative religious/racial identities (white supremacy) using a variety of methods (ethnography, history, cultural studies, sociology).

Taboos in the Field: Background and Theory

As I mentioned above, the course is a meta-critical reflection on the categories of race and religion in religious studies scholarship. This content offers particularly rich grounds for thinking about the ways in which both race and religion are not simply descriptive terms, but rather, concepts that construct and maintain power dynamics in the field of religious studies while also having broader cultural, political, and material implications. The theoretical background for the course is in many ways grounded in Michael Omi and Howard Winant’s racial formation theory, with particular attention to the “ethnicity paradigm” in American race theory. The ethnicity paradigm is a fantastic example of the power of elision, of the ways in which not speaking about race will not eradicate the problems of racism. To further illustrate this, we read articles in which authors respond to one another—framed as conversations between members of a community of scholars—that highlight the significance of taking race seriously as a category. These readings model scholarly discourse on race and religion in both positive and negative ways, and they add resources to our critical-thinking toolkits. Thinking about readings in dialogue gives students an opportunity to see scholarship “at work” and to analyze the discourse. Students write responses to readings, discuss them in class, and revise and repeat.

Our class readings also illustrate the theory that undergirds my own anti-racist pedagogy. They exemplify the ways that knowledge is constructed and contested by communities of scholars, and we practice ways of entering into these discussions with compassion and critique. One set of readings is Robert Bellah’s “Civil Religion in America” and Charles Long’s “Civil Rights—Civil Religion: Visible People and Invisible Religion” from the same collected volume, American Civil Religion. In this pairing, Bellah’s classic text on civil religion is the starting point; he uses “religion” to interpret the beliefs, symbols, and rituals of American national identity. Long offers a response that carefully frames the power and possibility of civil religion as an “American cultural language,” one that not only creates a unifying American identity, but also renders racial and religious minorities invisible. Long also discusses how this language constructs the field of American religious history, and he critiques scholars’ roles in historical elisions as well. Later, students read Nathan Glazer’s “The Emergence of an American Ethnic Pattern” followed by Ronald Takaki’s “Reflections on Racial Patterns in America.” In this pairing, Takaki is directly responding to Glazer’s optimistic view of American progress with historical examples that highlight the differences between ethnic and racial patterns in policy, history, and American identity.

The crucial shift of the critical lens in both of these pairings revolves around the conscious acknowledgement of “race” by Takaki and Long, which serves as a response to the ethnicity-centered analyses of Bellah and Glazer. Students are asked to compare and contrast the pairs, looking for the ways in which race, ethnicity, and religion are defined and utilized as scholarly categories. What emerges is often a realization of the constructive power of these concepts. Long and Takaki shift the narrative of American history by simply beginning to recognize and talk about religion, race, and the elision of race. The ways in which paradigmatic structures of power are maintained in scholarship are multiple, and throughout the semester we diversify our readings in terms of scholars, methods, and objects of study. I try to actively be as transparent as possible about the theories I use as pedagogical models for the class by incorporating them into the syllabus.

Conclusions

Class readings, writing, and discussion allow students opportunities to sharpen their skills as they analyze scholarship, critique it, and practice it. I want them to see how race works to maintain and disrupt scholarly practices and power relations in the field of religious studies. I want students to see that scholarship is powerful, and that how we study religion constructs religion. I want them to ask and answer several questions about the academic field of religious studies: Is there anti-racist religious studies scholarship? What does it look like? How do scholars do it? What are the methods? Theories? Interactions? Data? Can we dismantle the structures of power in our disciplines? This course cannot answer all of these questions. But it is meant to begin the conversation. In the service of leaving the course (and the field) open-ended for students, I struggle to present scholarship descriptively and not prescriptively. Racial formation theory offers us tools for critiquing scholarship, but it is also a theory that ultimately needs to be critiqued.

Our early readings and discussions provide the foundation for our later evaluations of contemporary events and scholarship and set the stage for the more difficult questions that arise. They serve as shared content for the course, but also as models for how to talk about race and religion. One of the guiding questions of the course is whether it is possible to study religion in the United States without carefully considering race. And if it is the case that race has a profound role in what we call American religion, then as community of scholars, we need to be able to communicate clearly about it: it cannot be taboo. At the end of the semester, after building community that can discuss difficult topics with clarity and precision, students leave the class with tools will help them navigate the world inside and outside of academic spaces. This is the aim of all of the anti-racist strategies that I use in my courses.

None of these ideas are truly my own. I have borrowed from many others, and it is important to acknowledge this and to give credit where it is due. This class and the readings I use in the example above were adapted, with permission, from a graduate class I took with Rudy Busto at University of California, Santa Barbara. My contribution here has been to give the course an undergraduate orientation—meaning fewer readings, directed writing assignments, and an introductory approach to both content and form. The Taboo classroom activity above is also an adaptation. One of the best discussion courses I took as an undergraduate was a writing course taught by Barrie Talbot at Missouri State University, and it began with a game of Taboo. The sharing of resources and strategies is a necessary part of anti-racist pedagogy. A culture of collective learning is exactly what I try to cultivate in my classes, and it is what I hope this issue of Spotlight ultimately accomplishes as well.

Resources

Adams, Maurianne and Lee Anne Bell, et. al, eds. Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice, 3rd edition. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Omi, Michael and Howard Winant. Racial Formation in the United States, 3rd edition. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2015.

Richey, Russell E. and Donald G. Jones, eds. American Civil Religion. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

Smith, Jonathan Z. On Teaching Religion: Essays by Jonathan Z. Smith. Edited by Christopher I. Lehrich. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Takaki, Ronald, ed. Debating Diversity: Clashing Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity in America, 3rd edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Martha Smith Roberts is an assistant professor of religion at Denison University in Granville, Ohio. Her current research and teaching interests include North American religious diversity and pluralism, race and ethnicity studies, and social justice. Her courses focus on the diversity of the American religious landscape, especially the ways in which race, gender, and ethnicity are connected to religious identities and the significance of material culture and lived religious experience in American life. She is currently researching the display of the human body and religious pluralism in America and working on a collaborative research project examining the various spiritualities within the hula hooping subculture. She researches and writes with Culture on the Edge, a scholarly working group and peer-reviewed blog that examines religion, culture, and identity. She is the executive secretary and treasurer for the North American Association for the Study of Religion, and she also serves on the board of directors for the Institute for Diversity and Civic Life, a nonprofit educational organization based in Austin, Texas.

Martha Smith Roberts is an assistant professor of religion at Denison University in Granville, Ohio. Her current research and teaching interests include North American religious diversity and pluralism, race and ethnicity studies, and social justice. Her courses focus on the diversity of the American religious landscape, especially the ways in which race, gender, and ethnicity are connected to religious identities and the significance of material culture and lived religious experience in American life. She is currently researching the display of the human body and religious pluralism in America and working on a collaborative research project examining the various spiritualities within the hula hooping subculture. She researches and writes with Culture on the Edge, a scholarly working group and peer-reviewed blog that examines religion, culture, and identity. She is the executive secretary and treasurer for the North American Association for the Study of Religion, and she also serves on the board of directors for the Institute for Diversity and Civic Life, a nonprofit educational organization based in Austin, Texas.

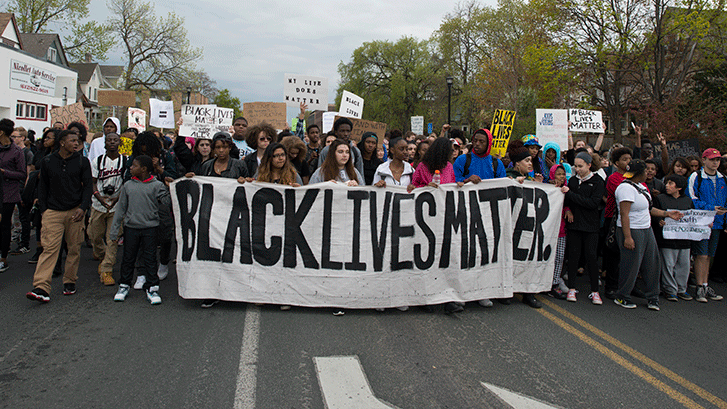

Image: “Students march because Black Lives Matter,” Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 1, 2015. Photo by Fibonacci Blue (CC BY 2.0).