Whiteness Studies—Why Not to Teach It (As an Untenured Professor)

Unlike my colleagues contributing to this Spotlight, my emphasis is less on what one could or should do and more on what one should not do. Specifically, I recommend that you do not teach a course on whiteness studies as an untenured professor, lecturer, or (god-forbid) as an adjunct. Likely, my colleagues might disagree, and I too hate to take this standpoint, but I ask that you at least consider my perspective as one end of the spectrum, where I advise excessive preparation for the potential negative consequences of teaching antiracism.

Teaching Strategy: Avoid Teaching a Course Titled “Whiteness Studies” without Tenure

I will introduce my strategy like I introduced it to my philosophy of race class. This course focuses on how scholars in academia and theology have worked to remove systems of racism from the thought, structures, and institutions of their respective fields. The examples are primarily African Americans and Asian Americans because these are my areas of expertise, and these scholars inevitably touch upon the construction of whiteness. Way back in October 2017, I was teaching the philosophy of race course and within the span of one week there were the Las Vegas mass murder and the reigniting of the NFL kneeling debate. In the wake of these events, I opened my class to the option of discussing either or both of these topics using the tools we had been developing in class (a tactic that I use for any course that would appropriately shed light on a recent event). Students voted unanimously that this was okay (and I find that unanimity is important for making these discussions productive), and they all wanted to discuss the Las Vegas shootings.

I reviewed theories that they had studied and that shed light on the event—essentially arguing that while our class’s study of race in the United States focused on the perspectives and struggles of racial minorities, our class was always studying whiteness and how white supremacy functions. I then expanded our toolset by explaining that to understand the Las Vegas shootings we would need to study whiteness more directly. I briefly built on our course’s knowledge-base to illustrate how the normalcy of whiteness oppresses both racial minorities and those with white status. Namely, in order to maintain normalcy, the status must be protected from intrusions from below, but besides these sporadic disturbances, the state of being normal can get boring. As a result, socioeconomically secure white people end up competing with each other to seem more than normal, and attractiveness and self-satisfaction come by rising above the normal with marks of taste, power, and wealth. After the Las Vegas shooting, the brother of the alleged gunman said that he was “just a guy”—a normal guy who was a multimillionaire, high-stakes gambler, and leisure pilot in addition to a gun enthusiast. In class, I did not argue that whiteness was the sole cause of his desire for violent difference, but an important factor and angle of analysis to consider.

Students loved the analysis and ensuing discussion and debates, and requested that I offer a whole course on whiteness. My response was an unequivocal no. Yes, these days are perhaps the most important time to understand whiteness, but I cannot be that teacher, I cannot do that in my context, and I am not willing to take that risk at this point in my career. I then unveiled my paranoid vision of what might occur should I go against all these calculations.

Background and Theory: Know Your Location; Whiteness Studies; Paranoia

I heard from a psychologist that one of the first diagnoses of someone who expressed that they experienced racism was paranoia. Ponder the possibility that there is a vast conspiracy of wealth and power with great hatred towards you and with the goal to disrupt and/or to end your life—that is paranoid, and it also true of racism. In order to understand my paranoia/reality, it is important to know my social location. I am Japanese American, and during World War II my family’s fears became reality when they were forced into internment camps without cause and without due process, in large part because of society’s fears of their race. Additionally, being a Japanese American leaves me open to mischaracterizations of my scholarship on race, especially to the tactic of dismissing my critical analysis of past and present racism as revenge for the internment camps. I also am aware that in our political climate, anyone against racism can be regarded as working against all white people. In short, my social location and family history as a Japanese American provides intimate knowledge of the history, presence, and functions of white supremacy, but this location and history also damns me in the eyes of those defending it. Moreover, being on tenure track but without tenure, I am under the threat of termination for offending the politics of university administration—something I have seen happen with devastating results. Retribution would be swift and would likely be even more detrimental for those not on tenure track. In this light, tenure is not just job security and status but a rare protection of academic freedom and sanity, though by no means an impenetrable one.

* * * * *

With this wisdom, I have my paranoid vision:

When I offer “Whiteness Studies,” students would attend with the sole purpose of disrupting the class. They secretly record lectures and student interactions, and release a selective, edited portion to the anti-antiracism media. Then, my distorted face/voice would be the image of all anti-racism professors, and a portion of an argument or a misrepresentation of an argument would serve as the strawman for all anti-racist arguments in anti-antiracism media. My traumatized students would be media darlings as they recount the idiotic, abusive, and foreign [fourth-generation American] professor who knows nothing about being white yet feels he can teach white people about their own experience. Concerned parents and community members lobby the school to have me fired along with all ethnic studies professors and any others who speak in support of me. Newspaper editorial columns appear decrying the state of the public university where taxes go to frivolous topics and privileged professors. My social media and school email accounts become a cesspool of trolling, while my colleagues, family, and friends are forced to defend me or to distance themselves from me personally and on social media. In response, my university, department, and colleagues may help defend me, but not that much. I get taken to court, lose my job, lose lots of colleagues and friends, stress out my family, worry about my family’s safety (and my own), and probably more. Tenure would help with the job part, maybe even with the court part a little bit, but the other stuff not as much as I would need.

* * * * *

That is basically how I see my life after starting to teach “Whiteness Studies.” In addition to my social location, I have this paranoid vision because the items listed have actually happened to others in recent years. Moreover, I am at a state school in the South and relatively new to the region.* There are Asian Americans here but nothing like the support networks in the West and Northeast. And, significantly, the anti-antiracism movement is strong, organized, and endorsed by media empires and the President of the United States. I recognize that my physical, political, and social location puts me at the mercy of asymmetric power—and I should remind you that others are even worse off! Given my own evaluation of my social location, then I put forward that you do the same, and you may end up as or more paranoid; that is, appropriately afraid of anti-antiracism backlash.

I also have this vision because I have studied whiteness and white supremacy; there are structures, discourses, and epistemologies that are designed to protect whiteness, and they would not be deterred by an untenured professor. One key element of this protection has been termed “white ignorance” by Charles Mills, which is the epistemology designed not to see whiteness. As he details in his book chapter by the same name, white ignorance has been crafted both on false knowledge (e.g., the Civil War was not related to slavery) and an active denial of evidence that racism exists and white people contribute to it. Consequently, a course on whiteness would bring white students, university administration, media, and public to react by embracing false knowledge that contradicts the course’s knowledge. They would also reject the premise that race exists and the evidence that white supremacist ideas are openly embraced, that hate crimes are on the rise, and that white people need to understand their whiteness as much as minorities.

To this latter point, Mills argues that white ignorance has long been understood by racial minorities and is foundational to their double consciousness. For survival, they must know the realities of systematic racism and know how to see the world through white ignorance, lest they disrupt white people’s white-less vision which can evoke an angry response. A course on whiteness would purposely carry out this disruption. I could argue to students, public, and the media that this disruption is important for the health and knowledge of all; but, again, white ignorance does not hear any arguments that put itself under scrutiny. Consequently, my intimate knowledge of whiteness along with my study of racial minority scholars who have done the same—even though we have been forced to understand whiteness for generations and have studied it for our careers—would be rendered lies and grievance by white ignorance.

Given white ignorance, the political climate that supports white ignorance and white supremacy in general, and my location as a Japanese American man in the South at a state school without tenure, my teaching strategy is not to teach a course entitled “Whiteness Studies.” Note that I consciously include elements of whiteness studies in nearly every course I teach, such as the historical relationships of whiteness, nativism, and immigration and the popular culture depictions of others to define whiteness, but I do not choose to confront white ignorance more directly.

Conclusions and Extensions: Knowable Risks

When embarking on anti-racism work, do not be naïve. If racism were easy to solve, it would have happened already. And, just because you have the tools and knowledge to teach a course that is explicitly anti-racist (like “Whiteness Studies”), doesn’t mean you should. I advise awareness and a healthy paranoia. Teaching an explicitly anti-racist course at any point in US history has been dangerous; teaching one in today’s political climate parallels the peak racism (post-Civil War) of the 1870s, 1910s, 1930s, and 1950s and 60s.

In this light, if you choose to teach whiteness studies without tenure, consider it on par with the Civil Rights protests in the 1950s: you are at a lunch counter and just waiting for the angry white crowd to gather. Oh, and you don’t have SNCC and Martin Luther King, Jr. to provide a grand strategy, legal defense, media representation, and moral legitimation. These heroes led an extremely difficult path for civil rights; now imagine that path without that support. If you are willing to confront this paranoid vision, then your sacrifice may be remembered well in a few decades, but it is also possible that you may end up forgotten, with a criminal record, no academic career, and isolated in other ways—which is a current reality for many Civil Rights-era protesters.

I would rather learn from the experience of earlier anti-racist educators: Develop strong networks along with your own skill and fortitude. Develop a map of your network of support, including academic, legal, political, personal, and moral. Identify those who would truly support you and those who would likely not support you or who would likely work against you. Then, cultivate the positive relationships and perhaps try to understand the interests of the unsupportive others in your network. And, like I am sure someone has told you already: handle your business, do solid work in research, writing, and teaching, and, if you are in that increasingly rare position to be on that track, get tenure. In addition to this, make sure your family is on board. Then I would say, you are ready for the wild ride of teaching “Whiteness Studies”—an adventure in the classroom and beyond.

* Dr. Esaki has recently switched institutions, and at the time of writing, was teaching at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia.

Resources

Jones, William R. Is God A White Racist?: A Preamble to Black Theology. Boston: Beacon Press, 1973.

Matsuoka, Fumitaka. Out of Silence: Emerging Themes in Asian American Churches. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2009.

Mills, Charles. “White Ignorance.” In Race and Epistemologies of Ignorance, edited by Shannon Sullivan and Nancy Tuana, 13–38. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2007.

Tuana, Nancy and Shannon Sullivan, eds. Race and Epistemologies of Ignorance. New York: State University of New York Press, 2007.

Yancy, George, ed. Philosophy in Multiple Voices. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007.

Zack, Naomi, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Race. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Brett J. Esaki is a visiting assistant professor in the religious studies and classics program at the University of Arizona (PhD, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2012). He researches how American racial minorities creatively use religion and art to preserve, reinvent, and discover a sense of their full humanity. He specializes in intersections of Asian Americans and African Americans in areas of spirituality, popular culture, and comprehensive sustainability. His interdisciplinary research involves ethnography, performance studies, psychoanalysis, philosophy of race, ideology, and alternate intelligences. His book, Enfolding Silence: The Transformation of Japanese American Religion and Art under Oppression (Oxford University Press, 2016), explores the history of Japanese Americans preserving and hybridizing religious traditions through art. Japanese Americans found that silence is a nexus that avoids social oppression, is marginally accepted in art circles, and houses religious resources. His current book-length project, tentatively titled Asian American Radical Spirituality, examines the intersection of spirituality and radical politics among Asian Americans.

Brett J. Esaki is a visiting assistant professor in the religious studies and classics program at the University of Arizona (PhD, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2012). He researches how American racial minorities creatively use religion and art to preserve, reinvent, and discover a sense of their full humanity. He specializes in intersections of Asian Americans and African Americans in areas of spirituality, popular culture, and comprehensive sustainability. His interdisciplinary research involves ethnography, performance studies, psychoanalysis, philosophy of race, ideology, and alternate intelligences. His book, Enfolding Silence: The Transformation of Japanese American Religion and Art under Oppression (Oxford University Press, 2016), explores the history of Japanese Americans preserving and hybridizing religious traditions through art. Japanese Americans found that silence is a nexus that avoids social oppression, is marginally accepted in art circles, and houses religious resources. His current book-length project, tentatively titled Asian American Radical Spirituality, examines the intersection of spirituality and radical politics among Asian Americans.

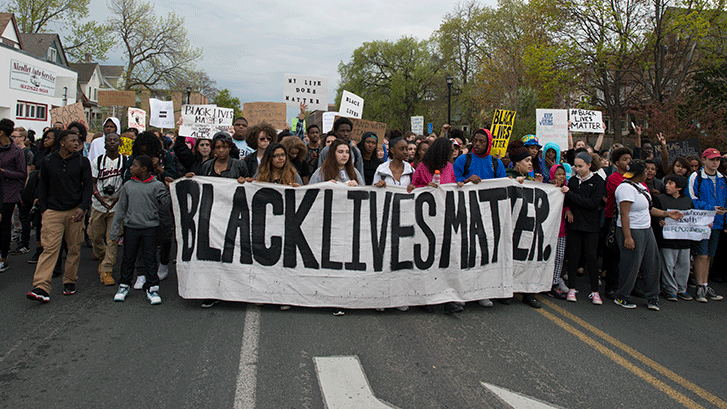

Image: “Students march because Black Lives Matter,” Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 1, 2015. Photo by Fibonacci Blue (CC BY 2.0).