Decolonial Approaches to the Study of Religion: Teaching Native American and Indigenous Religious Traditions

The Decolonial Classroom: Making Power Visible

The goal of many of my courses on Native American and Indigenous religious traditions is to understand contemporary Indigenous life in relation to colonial histories. I employ both a decolonial and Indigenist approach to these ends. A decolonial approach makes the mechanisms of colonial power visible. It denaturalizes our assumptions about Indigenous peoples and their religious traditions. For example, in my course “Global Indigeneities: Religion and Resistance,” we explore contemporary Indigenous movements for sovereignty and environmental stewardship in the Americas, Oceania, and Asia. Initial readings provide a broad theoretical framework for understanding both settler colonialism and Native American and Indigenous religious traditions, followed by regional examples of resistance movements. Once students have the basic theoretical tools to understand racialization, missionization, scientism, natural law, and criminalization of Indigenous peoples/religion as mechanisms of settler colonialism, they are better prepared to understand Indigenous stewardship movements as a profound expression of sovereignty.

As a Chicana of Apache descent, I feel obligated to use an Indigenist approach to pedagogy, which means using critical readings by Native scholars or those that center the voices and views of Indigenous peoples. Native-centered narratives often provide a more nuanced and tribally specific framework to understand sacred and interdependent relationships with land and spiritual power. Teaching these ideas is a layered and cumulative process. Students are sometimes reluctant to take the religious views of Indigenous peoples seriously. When Indigenous peoples frame plants, particularly medicinal plants, not only as persons but also teachers and relatives that provide the people with moral instructions, students are skeptical. Native-centered readings provide grounded examples that resist overly mystical readings. For instance, the Three Sisters: corn, beans, and squash are recognized by many tribes within US borders to have a familial relationship that asks these sister plants be grown together. Empirical study has confirmed that their co-planting produces a natural nitrogen cycle that fertilizes the soil, preventing depletion. As students consider the ethical instructions provided by these three sisters, they better conceptualize interdependence as a way of life broadly construed. Students’ curiosity to consider realities that differ from their own compels discussion, even if they remain skeptical.

We then explore, through regional examples, how overlapping histories of settler colonialism produce environmental crises. By asking “what is Indigenous stewardship? What might earth justice look like?” early on, we can later ask “what does it mean to understand the land—and its inhabitants—as sovereign?” Here, the objective is to understand how Indigenous philosophies of land/living serve as the political foundation for challenging settler dispossession. When Indigenous peoples continue to assert the land’s sentience, they are critiquing the dominant assumptions that it is inert—a position that has historically been used to justify its exploitation. I structure regional examples to include readings on the specific social-political history of the people, their religious worldviews, and their movements for sovereignty. For instance, a unit on Native North America may focus on Lakota water protectors at Standing Rock. The first class reading will explore Lakota/Dakota religion/political history with the United States, while the second reading will include a short ethnographic vignette and/or collection of news stories on the #NoDAPL movement at Standing Rock. The aim of class discussions is not only to understand these unique religious lifeways but also how they ethically inform Indigenous fights for survival.

I generally reserve five to fifteen minutes of class time to short documentaries, YouTube clips, and other forms of media about these environmental struggles in order to make the voices of those involved salient. For instance, I might show a clip of Mni Wiconi: The Stand at Standing Rock, a short documentary made by Divided Films, which interviews Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman, David Archambault II, on the fight for #NoDAPL. Presenting clips in class humanizes discussions that threaten to become too abstract by providing additional context for their human stakes. Judging from their weekly responses, students are most affected by these first-person testimonies, often expressing disgust, shock, or even outrage that Indigenous dispossession continues so egregiously within the United States and beyond.

Settler Colonialism, Troubling Knowledge Production, and Anti-racism

As religious studies scholars, it’s critical for us to explore the racialized perceptions of non-Western religious traditions and peoples as well as trace how these peoples continue to be structurally dispossessed as a result. We must provide a basic literacy of these traditions that simultaneously evaluates the lenses we use to understand them. Native American and Indigenous religious traditions were, until fairly recently, perceived by anthropologists and scholars of religion as failed epistemology, the primitive musings of less complex societies. Categorized as “animism,” their views were framed as childish, superstitious, and clear evidence they lacked the rationality to govern themselves or lay legitimate claims to their own lands. Indigenous peoples in the Americas were understood to be not only without reason, but also without true religion, making their full humanity suspect. Settler colonial projects relied upon these ideologies to justify Indigenous enslavement, genocide, and dispossession. These ideologies produced legal structures like the Doctrine of Discovery, a series of papal bulls that declared lands not inhabited by Christians open to seizure by right of “discovery” (theft), which became one of the most enduring tools of Indigenous dispossession. By acquainting students with a genealogy of settler rationale, they are better able to understand how the mysterious sleight-of-hand seizure was largely ideological and also squarely religious.

One of the reasons I pursued academia was to develop the social capital and expertise to teach others about how racism and Indigenous dispossession operate around the world. Like Brett Esaki, I am hyperaware of how dangerous teaching about white supremacy can be not only to my career but also, as a woman of color, to my personal safety. However, as a light-skinned Chicana, my Native features are less threatening to students/faculty, so I am sometimes (not always) perceived more favorably. As a junior scholar, I use this modicum of power and privilege to center Indigenous epistemologies in order to counter the legacy of Indigenous erasure and gross misunderstanding in the academy. Keeping this in mind, I take a two-pronged approach in the classroom. First, introduce the religious tradition, allow students to dismiss it as a curiosity (not all will, but some might) and then provide them with the intellectual framework to understand why the Western world systematically dismissed Indigenous knowledge. In other words, unpack the politics of this perception as a strategy of settler colonial power—one that has become so naturalized, it is assumed by most in the United States.

Some Native peoples in the Americas refer to the land as Turtle Island, remarking that it rests on the back of a turtle, and as others have said elsewhere, it is turtles all the way down. We can think of a decolonial pedagogy as de-naturalizing all the way down. Critical pedagogies explain how power works as a diffuse network of ideologies and institutions. Power is not just brute force or coercion. Reframing critical and anti-racist analytics with a settler-colonial lens helps us understand how coloniality operates all around us; how power is rooted in perceptions of the world, in “natural laws,” and the social hierarchies they produce. Part of the goal is to denaturalize assumptions embedded in Western epistemology that position Indigenous knowledge—and by proxy Indigenous peoples’ claims to land—as illegitimate. In the process, students begin to recognize how the institutions we take for granted as inevitable, such as the US and Mexican states, are socially constructed. They are also better able to see how racialization and power continue to shape the politics between them. Once students understand that the misperceptions of non-Western religious traditions and peoples operated as a strategy for dispossession, they begin to question their own biases. They may even be eager to explore the possibility that these traditions have something legitimate to tell us not just about inner life but also the complex nature of reality.

Speak From Your Own Position

At heart my courses are about ethics, understanding Indigenous ethics about right relationships to land and community. But also taking the time to consider what kinds of responsibilities we all have to the land and one another. They are one part philosophy and one part anthropological survey with decolonial critiques constituting their creamy center. Religious studies as a discipline has the flexibility to take an interdisciplinary approach to questions of meaning, the sacred, and ultimate concern. As we learn to use new anti-racist analytics, we can better consider how religious lifeworlds intersect with material horrors in the present in positive and negative ways. My particular goal for the course described above is for students to learn enough about Indigenous stewardship that they better understand the overarching relationship between contemporary expressions of neocolonialism/neoliberalism and environmental destruction. When they do, they may begin to advocate for intersectional forms of justice that center the well-being of the land, as they see how their own health and well-being are dependent on it.

My ultimate goal in the classroom is to cultivate a space where students learn how power operates and also about how marginalized peoples take their power back; how they empower themselves through their ethics and religious lifeways. In the process, students may reflect on their own relationships to and possibilities for power. It is also to seriously disrupt the stigma around Indigenous knowledge as “primitive” and irrational. I’ve noticed that when I’m teaching about Buddhism, students are often enamored by its own reference to interdependence, an idea rooted in dependent arising, a philosophical framework that describes all phenomena as interconnected. My guess is that racialization works differently here. Our orientalist conditioning allows us to consume the worldviews of the east as “exotic” and enchanting while still viable. Students are sometimes more dismissive of similar concepts rooted in Native America and other Indigenous communities because the stigma of “failed epistemology” is more pronounced. If we want students to understand racism as structural, we have to make these epistemological assumptions legible. We have to illuminate how these perceptions structure the very way we think about the world and the Other.

My only real recommendation is to teach about power from your own position. Complicate your positionality and relation to power to your students. This will model how they can think about their own positionality and why it matters to do so. I will occasionally assign a short paper that asks them to think about their own relationship to power and places explicitly. I adapted this “decolonial autobiography” assignment from multiple sources and it essentially asks students to answer the following questions in 600 words:

Think about the land that you were born into. Imagine the land itself has many layers—what is its history? Who were its first inhabitants or peoples? Or even the many inhabitants that coexisted there? What is its colonial history? What is your position in relation to this colonial history? How do you and your family fit in this picture? When did they arrive to this land (if known)? From where? Where do you live now? What is this place’s history? What is your relationship to the colonial relations of power in this land?

While teaching about settler colonialism and white supremacy is dangerous in these times, I find that many students, at least the many I recently taught at an elite small liberal arts college in the Northeast, were hungry for this contextualization, for these analytics. They are bearing witness to a chaotic and violent world and want to know why and how it came to be this way. Many are quite relieved to receive the tools to better understand it. When they do, they are better equipped to re-envision it entirely.

Resources

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books, 1999.

Denzin, Norman K., Yvonna S. Lincoln, and Linda Tuhiwai Smith, eds. Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2008.

Kovach, Margaret. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations and Contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Natalie Avalos is an ethnographer of religion whose research and teaching focus on Native American and Indigenous religions in diaspora, healing historical trauma, and decolonization. Her work in comparative Indigeneities explores the religious dimensions of transnational Native American and Tibetan decolonial movements. She received her PhD in religious studies from the University of California at Santa Barbara and is currently a Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Associate in the religious studies department at the University of Colorado, Boulder. She is working on her manuscript titled The Metaphysics of Decoloniality: Transnational Indigenous Religious Regeneration and Resistance. It argues that the reassertion of Indigenous metaphysics in diaspora not only de-centers settler colonial claims to legitimate knowledge but also articulates new forms of sovereignty rooted in just (and ideal) relations of power between all persons, human and other-than-human. She is a Chicana of Apache descent, born and raised in the Bay Area.

Natalie Avalos is an ethnographer of religion whose research and teaching focus on Native American and Indigenous religions in diaspora, healing historical trauma, and decolonization. Her work in comparative Indigeneities explores the religious dimensions of transnational Native American and Tibetan decolonial movements. She received her PhD in religious studies from the University of California at Santa Barbara and is currently a Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Associate in the religious studies department at the University of Colorado, Boulder. She is working on her manuscript titled The Metaphysics of Decoloniality: Transnational Indigenous Religious Regeneration and Resistance. It argues that the reassertion of Indigenous metaphysics in diaspora not only de-centers settler colonial claims to legitimate knowledge but also articulates new forms of sovereignty rooted in just (and ideal) relations of power between all persons, human and other-than-human. She is a Chicana of Apache descent, born and raised in the Bay Area.

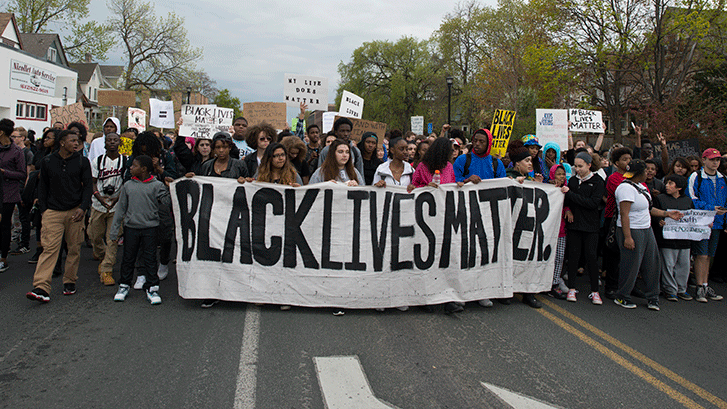

Image: “Students march because Black Lives Matter,” Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 1, 2015. Photo by Fibonacci Blue (CC BY 2.0).