Skin in the Game: Raising the Stakes with The Race Card Project

Recently I had a front row seat at my oldest son’s kindergarten graduation. Before receiving their diplomas, the children performed a montage of lessons they had learned during the school year—reading, writing, arithmetic…and world cultures. They conveyed the lessons with a cursory description of major holidays that took place within the semesters.

I don’t object to using holidays as a touchstone, but I surely failed at hiding my disappointment in the execution of the lesson. One child told us about the whimsy of Christmas—a winter holiday celebrated by most families present, even those not identifying as Christian. “Jewish people,” another child said, celebrate Hanukkah, and preceded to describe the function of a menorah which was depicted on a poster he had colored. Then a child approached the mic to explain how “Some people celebrate Kwanzaa,” all the while holding a different candleholder scribbled on a poster.

Call this an occupational hazard, but I wasn’t disappointed in how little the students had learned about the problematics of comparison, but how much they had taken away from these lessons. In a 187-day school year, they discovered the importance of reading and writing one’s name. These kids had to memorize where and with whom they lived and how to get a hold of loved ones in case of an emergency. And every other week, my son and I racked our brains for show-and-tellable ideas that were simultaneously personal and pertinent to a given theme.

You can’t tell me that kids are only able to learn so much about a culture. They are trained to master their own. But then why is it apparently acceptable to essentialize another culture by way of kitsch and nameless generics? Rather than use this as an opportunity to present a primer on critical race theory and the history of religion, the more important takeaway from this parable is recognition that these kids were taught to judge certain books by their cover. Given the reluctance shown by so many of my students and colleagues to discuss matters of social difference, I have no problem suggesting that our so-called higher education has disciplined us into silence.

My point is simply that the anti-racist conversion for which so many pedagogues pray can only come after the stakes of its implications become increasingly diffuse. Students must have skin in the game such that they can no longer claim a position outside of the politics of identity where naiveté—feigned or authentic—is permissible. In my classroom, this means confronting the socially normative paradigms in which students are schooled all too well.

Teaching Strategy

My activity of choice for this is The Race Card Project (TRCP). The brainchild of award-winning journalist Michele Norris, TRCP is a micro-story telling tool to surface the dramas with which we for better or for worse identify—particularly in regard to social difference. It sets the table to discuss the many reasons why one’s truth claims do not necessarily constitute truth for someone else. And it’s as easy as this: prompt participants to express their truth about race…in six words. Answers can be funny, profound, creative, or serious. The only rule is that these six-words stories must be honest and true to the author’s experience.

The activity makes clear that there’s a difference between talking about race and saying something about it. To set the tone, I have found success by displaying the online Race Card Wall, which displays random submissions from the tens of thousands of cards collected since 2010 from all over the world. One can even search for a term like “religion,” the name of a world religion, or some religious term to see what appears. I give students a few moments to read the stories as they stream across the screen. Then I invite them to read aloud those that pique their curiosity. Students may feel affirmed, shocked, intrigued, or even disgusted. But they are always interested!

That’s when I invite the class to share their own six-word stories. We maintain silence while students compose and then listen to their classmates read aloud. This makes room for students to express themselves without concern of unwarranted commentary. It also coaxes participants into a posture of active listening.

Part of why we say so little of substance about race and difference is because we know that just like “sticks and stones may break our bones,” words can bring a world of hurt. The optimum forum for sharing depends upon size of the class. My decision to have students go around a circle, pair up, or form small sharing groups is based upon the likelihood that I can (1) maintain a zero body-count as a result of the discussion, (2) assure that students won’t be oppressed (not to be confused with offended) in the process, and (3) help students be less “jerky” than when they arrived.

One might think that last point a little harsh, but I literally say this because they already know that failure here will do more harm than good. They want a space where they can be as honest as they are ready to be, creative as they know they can be in the moment, and prepared to listen as much as they are ready to speak. My role as teacher is not to bring racial reconciliation. It is to help students reckon why we have yet to do so. TRCP fosters an awareness of the consonance and dissonance that are products of how we have come to understand social difference.

Background and Theory

Cliché as it may sound, I premise my use of the TRCP upon the notion that discourses such as race and religion are learned behaviors. “Hate is taught,” so the trope goes. The problem with this articulation though is that it equates difference—rather than prejudiced evaluations, structures, and actions—with hate, hence why people either avoid substantive conversations about difference with those they perceive as different from themselves (e.g., preaching to “the diversity choir”) or the terms for discussion became so vague that they no longer speak to the nuance of our tortured realities (e.g., “I’m colorblind.”). TRCP provides a lexicon for reading and writing one’s truth emphatically.

Yet as a scholar of scriptures, I also understand that the life-texts we study have the potential to attract and repel. We know too well how humans authorize such deeds. A classroom committed to making sense of our issues should have us think twice (and then some) about the lessons we teachers impart.

For starters, if we can recall the historic role of religion and race as university cornerstones (however worn), and if we can remember the shadow side of such monuments, are we not warranted to consider the extent to which we are teaching students to be “white”? I am not speaking here about the accident of phenotype as much as the pathology of those James Baldwin says have come to “think they are white,”—those complacent with the fanatical hope of a safety linked to specialness even at the expense of those they deem “other.” I think we too easily forget that white supremacy was and is just as tutored an affair as even the most decolonized syllabuses. The candor required by TRCP reveals how this is so.

I don’t come from a particularly activist branch of religious studies, but I suppose my work falls in line with Patricia Hill Collins’s allegorical twist on the Hans Christian Andersen story, “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” Her reading associates the emperor with dominance; and each new outfit, the many shapes of social inequality used to keep him in power. In the sharing of stories in the classroom we can do the important work of asking how we became ashamed of our nakedness that we would dress this way or that. TRCP unveils the classroom’s potential for reexamining how power comes into style.

Conclusions and Extensions

I have used TRCP in three different higher educational settings over the past six years, and no experience has been identical. I say that as a way of encouraging you to teach with TRCP free of the expectation that there’s a “best” way to do so. My only advice is to free yourself from expecting the class to end up somewhere, and just trust that the conversation will go in a way that will complement your larger classroom goals. I can only extend such an admonition with the benefit of hindsight.

That said I need to be honest with you. I have had reservations writing this essay out of fear that TRCP will become yet another band-aid applied to the deeper, system-wide cuts inflicted within our institutions. And as I commit words to the page, I am in the midst of an institutional transition that has me wondering whether TRCP will work in my new classrooms. Once I give up the notion that some good must come out of the TRCP exchange, my composure begins to return. I remember that at the end of the day TRCP is nothing more than a way for students to create a frame of reference for critically approaching social difference.

Now I’m switching my focus to a different question that I also recommend to you: “What opportunities does your classroom present?” In mine, the collected stories have provided data for us to analyze the politics of identity on our campuses. For instance, when I taught at California State Polytechnic University-Pomona, in Los Angeles, students in my general education course went away with a greater appreciation for the imbrication of ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and other social indices. At Shenandoah University, it helped students to ask each other what they had been too afraid to ask. At Elizabethtown College, students puzzled through collected stories to practice discourse analysis and followed up with contributors to learn the background behind the six-word stories as a means of developing ethnographic skills. Each application became high points in my course scaffolding and teaching experience.

What I did not expect was how the frankness of our class exchanges would inspire students to use TRCP for their own constructive purposes. For instance, at Elizabethtown College, a few students of color suggested using TRCP across the college after an anonymous racialized and homophobic threat was found on a campus marker board. The students—some of whom had been in my classes—believed TRCP could help the campus reclaim the signifying power of words. I agreed to help assist students with their campaign while committing my introductory class to the task of analyzing the findings in fall of 2015 and spring of 2016.

By most measures the project was a success. It garnered local media attention. Our campus partnered with TRCP as a spotlight school. Michelle Norris visited our campus and helped students, faculty, staff, and administrators reconceive their commitments to inclusive excellence. Campus leadership even allocated more resources toward student requests for a mental health services and inclusion-focused meeting space. Real talk can go a long way.

However, there can be limits, even costs to stretching the TRCP as teaching tactic into an educational program. For starters, the campus six-word story campaign at times became a victim of its own success. People would benignly ask me what I was planning to do next as if this work was my job and not our job. And while my introductory students gained invaluable experience conducting action research, quantitative data from my course evaluations suggests that these experiences lowered their perception of learning and academic performance regardless of their demonstrable proficiencies. In other words, they were worn out. And I share their sentiment. Such is the price of hard work and success.

Even though my students beamed with the pride of a job well done and an expanded skill set, I wonder whether the price was too high? Were I to do the campus-wide six-word story project again (and I absolutely would), I’d think even more carefully about the stakes of playing The Race Card Project in the classroom. At what point do high-impact learning practices become detrimental to the health of students? I realize that the answers aren’t black or white. It is more a matter of learning and unlearning the lessons that make difference and make a difference. And that’s a conversation worth having. Teachers and administrators need to go first.

Resources

Baldwin, James. “On Being White and Other Lies (1984).” In Black on White: Black Writers on What it Means to be White, edited by David Roediger, 177–180. New York: Schocken Books, 1998.

Coates, Ta-Nehesi. Between the World and Me. New York: Spiegel and Grau, 2015.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Collins, Patricia Hill. On Intellectual Activism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013.

Norris, Michele. The Grace of Silence: A Family Memoir. New York: Random House, 2010.

Richard Newton is an assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Alabama. He received his PhD in critical comparative scriptures from Claremont Graduate University. Among other places, he has published in the Journal of Biblical Literature and Method & Theory in the Study of Religion. His interests include theory and method in the study of religion, African American history, the New Testament in Western imagination, American cultural politics, and pedagogy in religious studies. Specifically, Newton’s research explores how people create “scriptures” and how those productions operate in the formation of identities and cultural boundaries—all of which will be discussed in his forthcoming book, Identifying Roots: Alex Haley and the Anthropology of Scriptures (Equinox, 2019). You can see more of his work, including blog posts, his podcasts, and video at his site, Sowing the Seed: Fruitful Conversations in Religion, Culture, and Teaching.

Richard Newton is an assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Alabama. He received his PhD in critical comparative scriptures from Claremont Graduate University. Among other places, he has published in the Journal of Biblical Literature and Method & Theory in the Study of Religion. His interests include theory and method in the study of religion, African American history, the New Testament in Western imagination, American cultural politics, and pedagogy in religious studies. Specifically, Newton’s research explores how people create “scriptures” and how those productions operate in the formation of identities and cultural boundaries—all of which will be discussed in his forthcoming book, Identifying Roots: Alex Haley and the Anthropology of Scriptures (Equinox, 2019). You can see more of his work, including blog posts, his podcasts, and video at his site, Sowing the Seed: Fruitful Conversations in Religion, Culture, and Teaching.

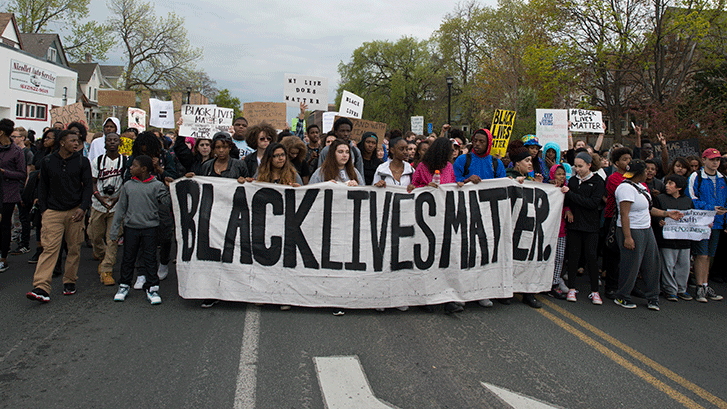

Image: “Students march because Black Lives Matter,” Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 1, 2015. Photo by Fibonacci Blue (CC BY 2.0).