“Saying the Wrong Thing”: Experiences of Teaching Race in the Classroom

Students at Warren Wilson College, where I have taught full-time over the past five years, have often told me in office hours that they do not feel “safe” discussing race in the classroom. They are eager and motivated to learn scholarly content and to analyze their experiences, but they are very reluctant to articulate their thoughts out loud. The college is politically liberal and predominantly white (about eight percent of the students are students of color, including international attendees); it is small (about 500 students) and rural. Most students live on the campus. Thus it is a place where students know each other and reputation matters a great deal. To “say the wrong thing” is to potentially be called out, or even labeled a racist.

Teaching predominantly white classes about race in such a context can be challenging. While students self-select into classes and thoughtfully engage with texts, they often feel that they do not have the authority to speak about race. They are often startled to read primary thinkers, such as Immanuel Kant, who argued that white people are not a race, and to consider that the term “race” includes white people. Many of these students grow up in homogenous environments in which they rarely encountered people of color, and indeed, that is still often the case on campus.

For several years, I have used informal and formal writing assignments to provoke students to a deeper space of vulnerability in their learning process. I think it essential that students encounter thoughts about race on three dimensions: (1) learning historical constructs of people of color; (2) internalizing the voices of people of color who have deconstructed racist constructs; and (3) challenging their own myopia and behavior. In this article, I will discuss a classroom assignment, as well as new insights I’ve gleaned, to illuminate how students can more deeply discuss race and racism in a homogenous environment.

Pedagogical Strategies for Teaching about Race in Predominantly White Classrooms

In my current academic position, as well as in my last academic position, I have dedicated one class period to stepping back and facilitating conversation about personal identity. I typically do this exercise in the second half of the semester once students have had a chance to learn about historical constructs and to read several texts from the perspectives of people of color (such as W.E.B. DuBois, Franz Fanon, Malcolm X, and James Baldwin). Students spend approximately thirty minutes writing a worksheet consisting of the following questions:

- How do you describe your racial identity? How do you describe your ethnic identity?

- Does your racial or ethnic self-identity differ from how other people identify you? If so, how?

- What are your understandings of race and ethnicity?

- How does your appearance relate to social privilege(s) in mainstream society?

- What are systemic patterns of racism that you observe in general society today? How do you participate (even inadvertently) in these patterns?

- How would you describe race and class dynamics on campus?

- How do you feel about the information we have covered in class this week?

- Is there anything else that you would like to add pertaining to your perceptions/ experiences of race?

We then spend approximately fifty minutes discussing the students’ responses to select questions. I ask students what question they would like to address first and we open the conversation to the entire class.

I find that this exercise, particularly when students have had a chance to reflect at length after reading personal narratives, as well as political analysis, eases the fear of “saying the wrong thing.”

At the same time, students will still stumble and feel awkward, even paralyzed. I can relate to this anxiety, and just recently had an experience with a group of people of African descent in which I felt I had “said the wrong thing.”

I recently attended a three-day gathering with a Buddhist organization, during which I had ample opportunity to reflect on the process of creating safe spaces for conversations on race amongst meditation practitioners of color who were coming together for the first time. I am rarely in a position to participate in such groups as a conversation partner, rather than a facilitator. During this gathering, the experience of engaging as a peer rather than guiding as a professor allowed me to gain a greater sense of why students may not feel safe talking about race in class: it can be frightening to say “the wrong thing,” as many students have told me during office hours. At one point, participants broke out into racial caucuses to deepen the conversation on identity. The starting question for my caucus—the Black caucus—was provocative: what complicates Blackness for us? It led to an intense conversation that spilled over into a breakfast gathering the next morning.

I relate this story for two reasons: (1) Blackness is complicated for people of African descent; and (2) at one point, I found myself extremely anxious at having said “the wrong thing.” Even though I was able to approach the person I triggered at the end of the session, I found myself shutting down and unable to sleep well; I replayed the experience over and over in my mind. I also felt that I learned something extremely valuable: the ways in which I can try to fix other peoples’ painful feelings, as well as my penchant to over-intellectualize rather than simply be present with the trauma that is being expressed. I have sat Buddhist retreats for more than thirteen years, but this gathering deepened my awareness of “what complicates Blackness” for people of African descent, how we can trigger each other, and how we can create healing spaces for one another.

The experience of engaging in race-based caucuses with Buddhist practitioners also deeply sensitized me to the experiences of white students who are encountering the worldviews of people of color in intimate ways. I teach several race-related classes at Warren Wilson College. I typically have one or two students of color in each of my classes. Thus my teaching strategies must take into account that many of the students who enroll are white students with little experience engaging readings by people of color or conversing with students and faculty of color.

Background and Theory

I was motivated to introduce this reflection practice into my courses on race after a student of color approached me in the spring of 2009 and said that she felt there were not many opportunities to discuss race on campus. At the time, I was teaching courses on criminal justice as guest faculty at Sarah Lawrence College. The student and I developed the questions together; I then asked several friends who facilitate anti-racism workshops to look them over and critique our language. The final list of questions is one that I have used each semester for almost ten years.

As aforementioned, I suggest that the texts and questions we bring into the classroom are meant to facilitate growth individually and collectively. Bloom’s Taxonomy has been particularly important for parsing the difference between cognitive and affective domains of learning. Lorin Anderson, a student of Bloom’s, created a pyramid of the cognitive learning process. Linda B. Nilson adapted Anderson’s pyramid to illuminate how it might be applied in the classroom.

Bloom’s taxonomy on the cognitive domain argues that there are six categories of developing intellectual skills:

- Knowledge: recall data or information

- Comprehension: Understand the meaning, translation, interpolation, and interpretation of instructions and problems. State a problem in one’s own words.

- Application: Use a concept in a new situation or unprompted use of an abstraction.

- Analysis: Separates material or concepts into component parts so that its organizational structure may be understood. Distinguishes between facts and inferences.

- Synthesis: Builds a structure or pattern from diverse elements. Put parts together to form a whole, with emphasis on creating a new meaning or structure.

- Evaluation: Make judgments about the value of ideas or materials.

On a cognitive level in the study of race, then, I want students to know, comprehend, apply, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate the texts they have engaged. But in teaching on race, the learning process must be much more extensive: it must impact the Affective Domain, that is, the domain in which students engage emotionally and cultivate new values, appreciation, motivation, and attitudes. Bloom’s Taxonomy on the Affective Domain is striking in its guidance of how deeply students can engage new ideas, ultimately with the goal of internalizing (or perhaps expanding) new values on race and racism. Bloom states that people receive and respond to phenomena, leading to valuing, then synthesizing, and ultimately shifting their behavior based on these new values.

- Receiving phenomena: Awareness, willingness to hear, selected attention.

- Responding to phenomena: Active participation on the part of the learners. Attends and reacts to a particular phenomenon. Learning outcomes may emphasize compliance in responding, willingness to respond, or satisfaction in responding (motivation).

- Valuing: The worth or value a person attaches to a particular object, phenomenon, or behavior. This ranges from simple acceptance to the more complex state of commitment. Valuing is based on the internalization of a set of specified values, while clues to these values are expressed in the learner’s overt behavior and are often identifiable.

- Organization: Organizes values into priorities by contrasting different values, resolving conflicts between them, and creating a unique value system. The emphasis is on comparing, relating, and synthesizing values.

- Internalizing values (characterization): Have a value system that controls their behavior. The behavior is pervasive, consistent, predictable, and most importantly, characteristic of the learner. Instructional objectives are concerned with the student’s general patterns of adjustment (personal, social, emotional).

The goal of teaching undergraduates about race is fundamentally an affective practice. In my classroom, as I deconstruct familiar constructs, myths, and narratives and introduce students to the profound psychological shifts that people of color have articulated in response to racist constructs, I am working to facilitate changes in behavior. Thus reading texts is not solely an intellectual process; it is also an affective process in which students have the space to reorient themselves.

Conclusions and Extensions

Effective teaching on the study of religion and race must incorporate both the cognitive and the affective domains because we are teaching students about value systems, worldviews, ethical practices, and social justice. We are asking students to encounter different ways of thinking and to challenge to cultural values in multiple dimensions. And we are asking them to put aside familiar constructs and to embrace ideas which may feel threatening (what Charles W. Mills terms “an epistemology of ignorance”) as well as exhilarating (James Baldwin writes: “people who cannot suffer can never grow up, can never discover who they are.”)

I suggest that incorporating the cognitive and the affective domains into higher education is a practice that is becoming more and more widely implemented. Many colleges are expanding advisement so that the whole student experience is prioritized. There are broader initiatives to incorporate community engagement and expand education beyond the college campus. There are calls for “engaged scholarship” in which faculty and seniors think about the community impact of their research. There are increasing numbers of programs that bring students into prison settings to take classes alongside incarcerated students. All of these initiatives suggest that higher education is not solely about an elite practice of reading a canon and introducing new ideas; it is also about cultivating internal awareness in challenging, unfamiliar contexts and reflecting upon privilege and power, and finally, enacting social justice locally, nationally, and internationally.

Awareness of historical racial constructs and the myriad ways that people of color who have been deemed inferior have resisted such constructs is critical to cultivating both cognitive and affective learning. Furthermore, as Bloom notes, the ultimate purpose in education is to evaluate values as well as internalize values: to make judgments as well as to form character. We want students to not only think critically about race and racism, but also to interact in such ways that do not perpetuate racism in micro and macro practices. Thus, teaching on religion and race provides critical avenues for students to engage—to step out and perhaps “say the wrong thing”— and to continue to learn, and, ultimately to change, their psychological orientation towards the social contexts that surround them.

Rima Vesely-Flad, PhD, is an assistant professor of religion and social justice and the director of peace and justice studies at Warren Wilson College. She is the author of Racial Purity and Dangerous Bodies: Moral Pollution, Black Lives, and the Struggle for Justice (Fortress Press, 2017). She is currently at work on a second manuscript entitled Black Buddhists and the Black Radical Tradition: The Practice of Stillness in Racial Justice Activism. She holds a doctorate in social ethics from Union Theological Seminary, a master's degree from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, and a bachelor’s from the University of Iowa. She taught religion courses at Sing Sing Prison from 2004 to 2006, and also spent several years working with direct service organizations, alternative-to-incarceration programs, and political campaigns. Her honors include a 2007 Union Square Award for grassroots activists, a dissertation fellowship from the Forum for Theological Exploration, and the 2017 Teaching Excellence Award at Warren Wilson College.

Rima Vesely-Flad, PhD, is an assistant professor of religion and social justice and the director of peace and justice studies at Warren Wilson College. She is the author of Racial Purity and Dangerous Bodies: Moral Pollution, Black Lives, and the Struggle for Justice (Fortress Press, 2017). She is currently at work on a second manuscript entitled Black Buddhists and the Black Radical Tradition: The Practice of Stillness in Racial Justice Activism. She holds a doctorate in social ethics from Union Theological Seminary, a master's degree from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, and a bachelor’s from the University of Iowa. She taught religion courses at Sing Sing Prison from 2004 to 2006, and also spent several years working with direct service organizations, alternative-to-incarceration programs, and political campaigns. Her honors include a 2007 Union Square Award for grassroots activists, a dissertation fellowship from the Forum for Theological Exploration, and the 2017 Teaching Excellence Award at Warren Wilson College.

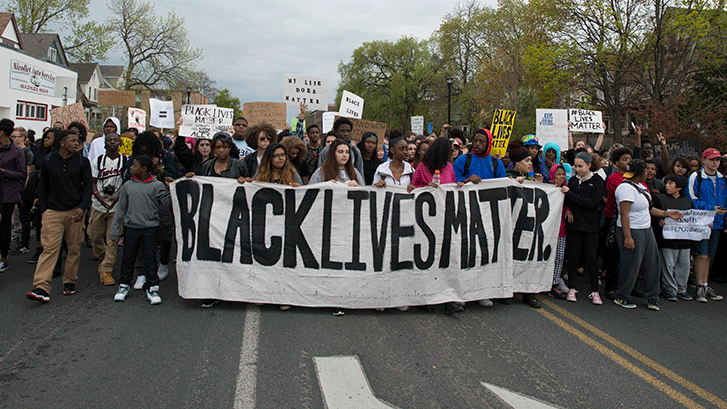

Image: “Students march because Black Lives Matter,” Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 1, 2015. Photo by Fibonacci Blue (CC BY 2.0).